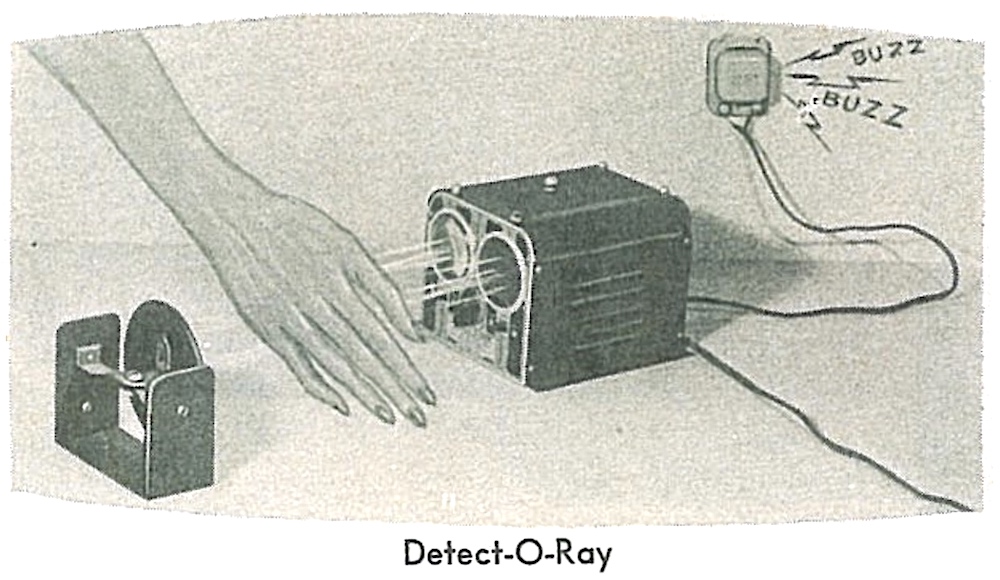

Museum Artifact: Detect-O-Ray Photo-Electric Switch, 1940s

Made By: Detect-O-Ray Company, 2622 N. Halsted St., Chicago, IL [Lincoln Park]

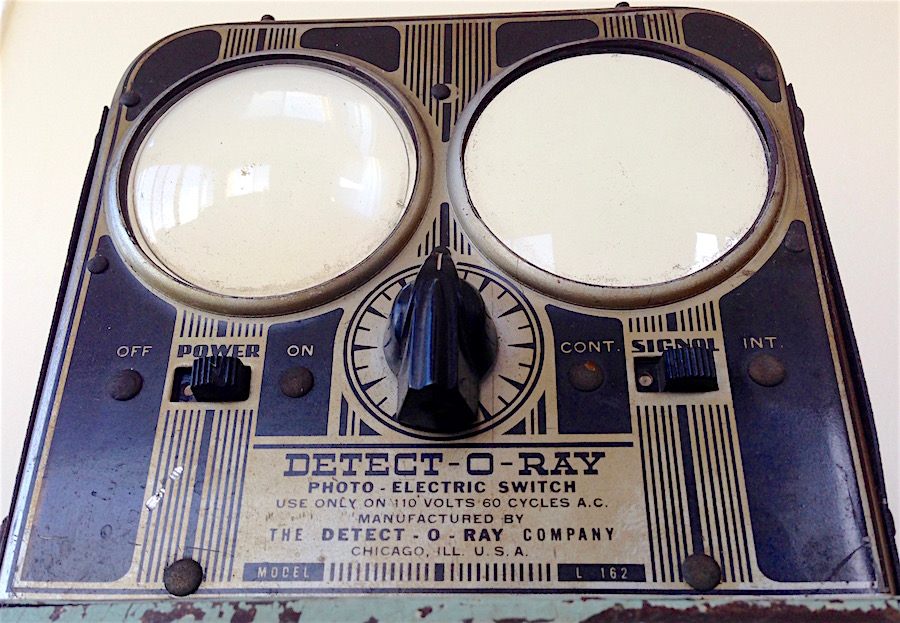

Its name sounds like a comic-book doomsday device and it looks more than a little like an evil robot owl, but sadly, the Detect-O-Ray is neither one of those things. In fact, this intimidating technological marvel of the World War II era was briefly marketed—of all places—in the pages of the F.A.O. Schwarz toy catalog.

“Detect-O-Ray—This is in effect an automatic electric switch which will operate, without the aid on the human hand, objects requiring not more than 6 volts A.C.,” the Schwarz write-up explained in 1944, seemingly presuming that a child would immediately understand the concept. “The ventilated black metal cabinet casts a light beam hardly visible (electric eye fashion) across a reasonable space to a reflecting mirror. Whenever this light beam is broken by a passing object, current is automatically supplied to a receptacle and from this receptacle current may be supplied to bells, lights, etc. This device may be put to many practical uses, but certainly every boy’s workshop should have one. The cabinet 6-1/2 x 5 x 5″ and comes complete with buzzer and mirror. Operates only on 110 volt 60 cycle A.C. Shipping weight 7 lbs. $31.50”

“Detect-O-Ray—This is in effect an automatic electric switch which will operate, without the aid on the human hand, objects requiring not more than 6 volts A.C.,” the Schwarz write-up explained in 1944, seemingly presuming that a child would immediately understand the concept. “The ventilated black metal cabinet casts a light beam hardly visible (electric eye fashion) across a reasonable space to a reflecting mirror. Whenever this light beam is broken by a passing object, current is automatically supplied to a receptacle and from this receptacle current may be supplied to bells, lights, etc. This device may be put to many practical uses, but certainly every boy’s workshop should have one. The cabinet 6-1/2 x 5 x 5″ and comes complete with buzzer and mirror. Operates only on 110 volt 60 cycle A.C. Shipping weight 7 lbs. $31.50”

For a bit of context, $31.50 is roughly $450 after inflation, so the Detect-O-Ray wasn’t exactly flying off the shelves like a hula hoop. For the kid with rich parents and a pillow fort in need of laser defenses, however, it made for a fine stocking stuffer.

Photoelectric switches are still in wide use today, albeit in much smaller, more refined designs. Their uses are broad and varied, but in general, the technology has long been associated with things like automatic doors, auto-timers for street lights, and yes, security systems.

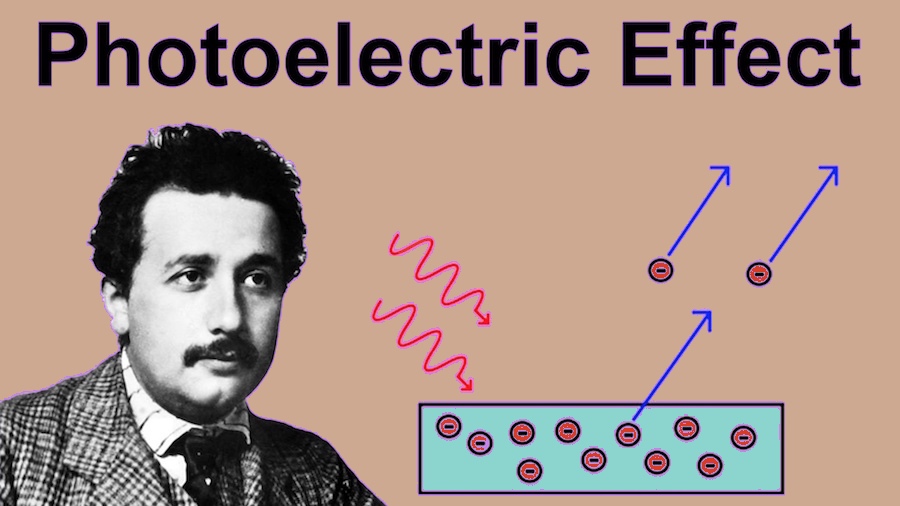

Utilizing research pioneered by the likes of Albert Einstein, early consumer devices of this sort started rolling out in the 1930s, known alternatively as “photocells,” “photoelectric sensors,” “photodetectors,” or “electric eyes,” to name a few. They were designed according to the principles of the “photoelectric effect,” which explains that when light energy (in the form of photons) strikes metal and other conductive objects, it sets loose “photoelectrons” that can then be utilized to create current flow. Accordingly, changes in light frequencies (and colors) can have major impacts on electrical charges. . . . I think that’s the idea anyway. I have an English degree.

In the case of the Detect-O-Ray, it might have been a “toy” in some respects, but if set up properly, it could offer quite legitimate benefits for the grown-ups, too—notifying a homeowner when an intruder (human or otherwise) crossed through the device’s single invisible beam; or even when a fire broke out. The same unit, when placed on the INT (intermittent) instead of CONT (continuous) function, could also work more like a doorbell, triggering a sound when a new customer entered a storefront, and/or counting how many people or objects passed through said door.

[A highly scientific rendering of the science behind the photoelectric switch]

[A highly scientific rendering of the science behind the photoelectric switch]

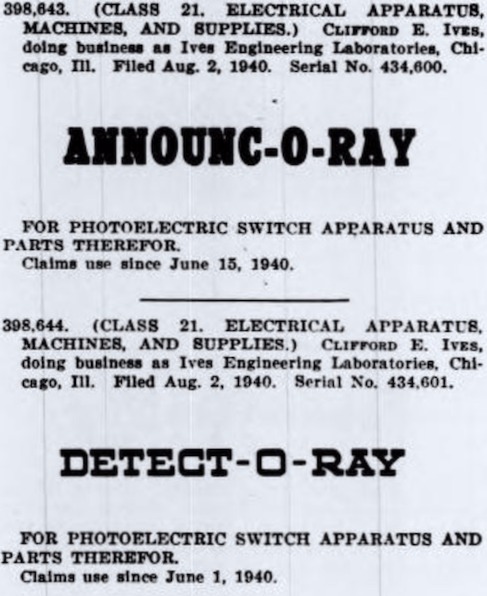

Even before the war, photocells were already being used to track cars on U.S. highways and the output of various machines in factories. Our Detect-O-Ray came along with the second wave of photocells, as the earliest version hit the market around 1940. It was trademarked by a 46 year-old, Chicago-based mechanical engineer named Clifford E. Ives, who had just enjoyed a major career breakthrough as the inventor of the Ives-Way Can Sealer in 1939.

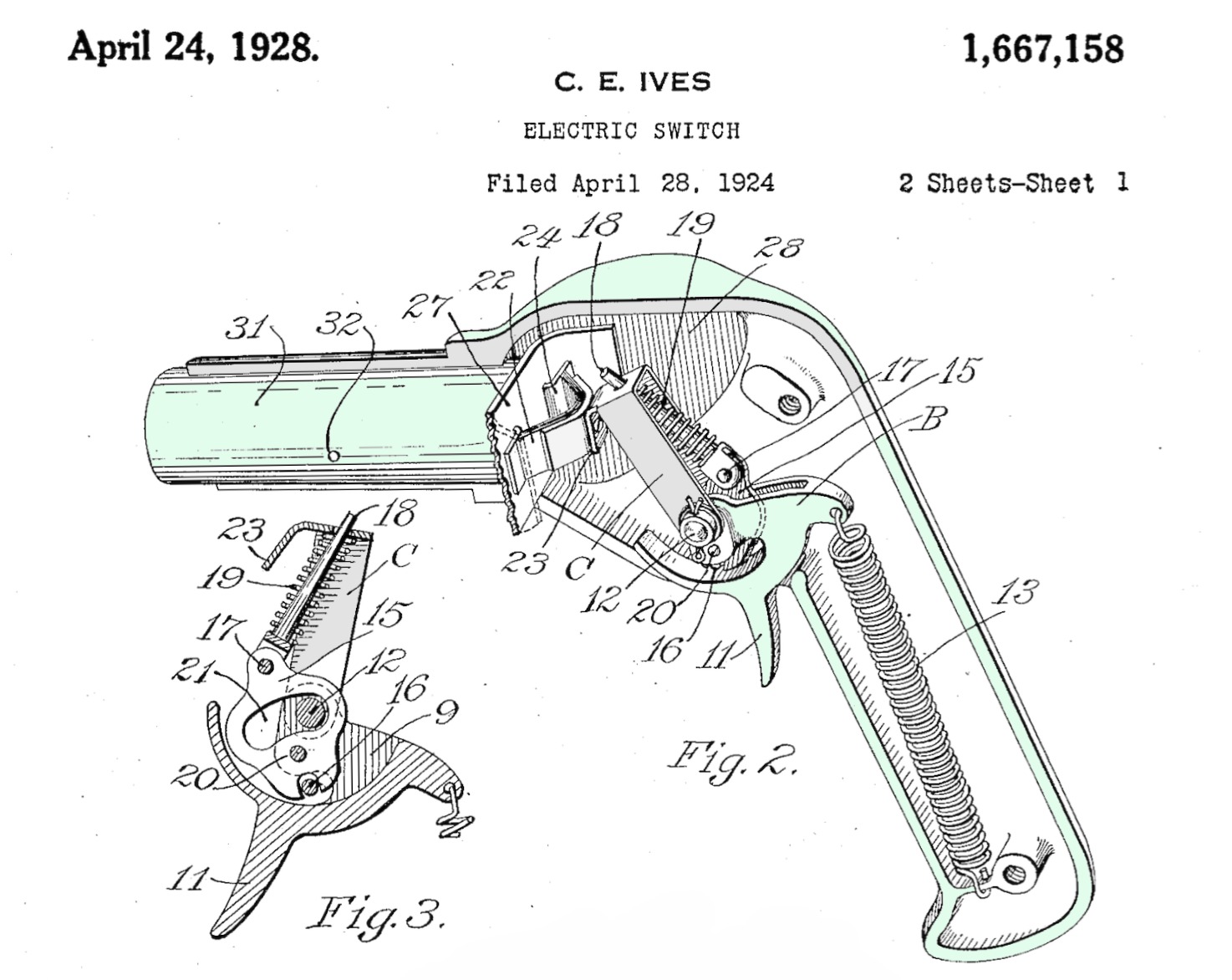

C.E. Ives was a graduate of Ohio State, where his older brother Frederick Walter Ives was head of the agricultural engineering department (he eventually had a campus building named for him). Clifford then served in the Navy during World War I, earned his masters at the University of Wisconsin in 1919, and finally headed south to Chicago to begin his own engineering career. Right out of the gate, he established the Ives Engineering Service in the Monadnock Block (53 W. Jackson Blvd), focusing on “automatic and special machinery”—this according to alumni notes from a publication called the Wisconsin Engineer. Ives also established himself as a budding master of the mechanical pencil, offering his technical drawing skills to several professional manuals in the ‘20s, including the Concrete Engineers’ Handbook and Handbook of Building Construction.

C.E. Ives was a graduate of Ohio State, where his older brother Frederick Walter Ives was head of the agricultural engineering department (he eventually had a campus building named for him). Clifford then served in the Navy during World War I, earned his masters at the University of Wisconsin in 1919, and finally headed south to Chicago to begin his own engineering career. Right out of the gate, he established the Ives Engineering Service in the Monadnock Block (53 W. Jackson Blvd), focusing on “automatic and special machinery”—this according to alumni notes from a publication called the Wisconsin Engineer. Ives also established himself as a budding master of the mechanical pencil, offering his technical drawing skills to several professional manuals in the ‘20s, including the Concrete Engineers’ Handbook and Handbook of Building Construction.

By the 1930s, Ives was married and living in Uptown (4417 N. Hazel Street), and by the end of the decade, he’d established a business called Ives Engineering Laboratories at 2400 W. Madison Street. That business offered a way to collect more of Clifford’s numerous inventions under his own umbrella, rather than freelancing for the likes of Sears & Roebuck and the U.S. Gypsum Company, as he had for years.

[A patent for a pistol-style electric switch from early in Clifford Ives’s career, 1928]

[A patent for a pistol-style electric switch from early in Clifford Ives’s career, 1928]

Ives was extremely prolific, patenting everything from traffic control systems to automatic elevator door locks, circuit breakers, cherry pitters, labeling devices, and continuous paper folders. He was all about using tech for supreme efficiency, so it made sense that he got into the photocell game.

Unfortunately, any specific details about Clifford Ives’s role in the development or production of the Detect-O-Ray are pretty much limited to his achievement in acquiring the trademark. For at least a couple years, the “Detect-O-Ray” name—along with a related product called the “Announc-O-Ray”—existed as brands under the Ives Engineering Labs banner. By 1942, however, a new business known simply as the Detect-O-Ray Company started running ads in trade journals like Product Engineering, touting its sole product.

Unfortunately, any specific details about Clifford Ives’s role in the development or production of the Detect-O-Ray are pretty much limited to his achievement in acquiring the trademark. For at least a couple years, the “Detect-O-Ray” name—along with a related product called the “Announc-O-Ray”—existed as brands under the Ives Engineering Labs banner. By 1942, however, a new business known simply as the Detect-O-Ray Company started running ads in trade journals like Product Engineering, touting its sole product.

“Detect-O-Ray can be plugged into a 110-volt, a.c. socket,” one ad read. “Sensitivity is adjustable as well as the type of light to be used. Available with a weather-proof housing for outdoor installations. The Detect-O-Ray Co., 216 N. Clinton St., Chicago, 111.”

It’s not clear if the Clinton Street address was an office, a manufacturing facility, or both. Either way, it wasn’t in use long. After the war, the company re-emerged at a Skokie address, then popped up again at a longer lasting headquarters: 2622 N. Halsted Street. Clifford Ives appears to have moved on well before that point, as a man named Otto G. Griesbach was serving as Detect-O-Ray’s president. Interestingly enough, the official Detect-O-Ray mailing address on Halsted also happened to be the private home of Otto and his wife Addie May. So this didn’t seem to be a particular large-scale operation.

Griesbach, like Ives, had Wisconsin roots, though he attended Notre Dame. He spent time as a farmer, as the manager of a bakery, and as an original co-founder of the Automatic Screw Machine Products Company. I am sure his career course made sense to him, but summed up in a sentence, it’s awfully scattershot. In any case, by 1940—at the same time Clifford Ives was trademarking the Detect-O-Ray—48 year-old O.G. Griesbach collected a couple patents of his own, for an electric circuit breaker and a holder for a glass coffee maker. He was finally turning a lifelong passion for mechanical engineering into his primary focus.

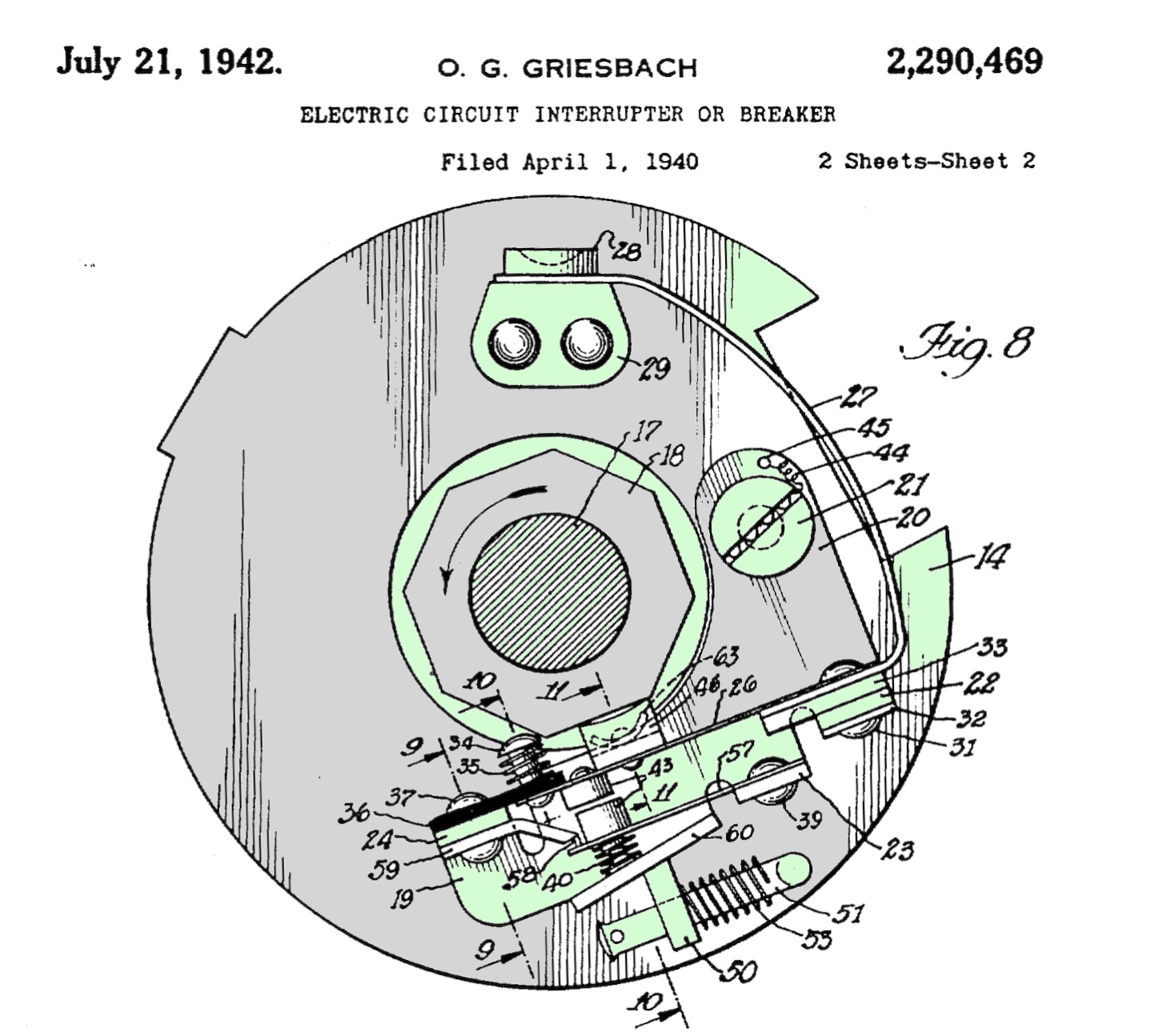

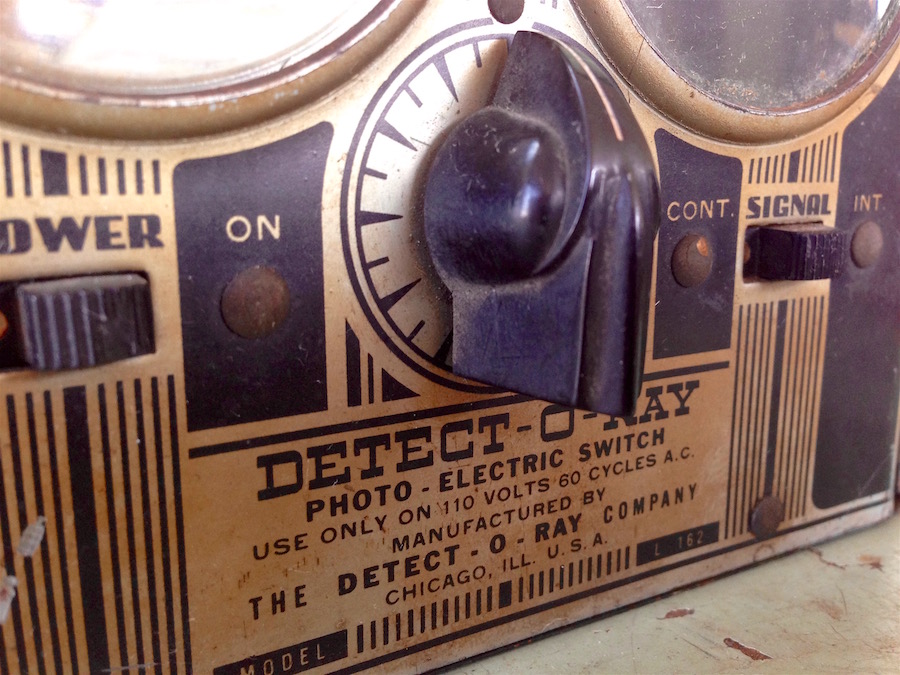

[Otto Griesbach wasn’t quite the inventor Cliff Ives was, but he did create this circuit breaker around the same time the Detect-O-Ray was first produced]

[Otto Griesbach wasn’t quite the inventor Cliff Ives was, but he did create this circuit breaker around the same time the Detect-O-Ray was first produced]

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is about all we know. How did Otto Griesbach come to lead the Detect-O-Ray Company in the 1950s? Unknown. Did he play a role in the creation of the product? Also unknown, as no patent specific to the Detect-O-Ray seems to exist. There is no current evidence of Griesbach and Ives—the only names we can tie to the device—ever occupying the same room. The eventual fate of the small company is also a mystery, though it seems like production ceased as new technology rendered it obsolete by the 1960s.

How the Thing Works

The photoelectric system, as I understand it, worked by directing a beam of light from an incandescent lamp to a mirror. This mirror then reflected the beam back to a lens that focused on the photoelectric cell within the Detect-O-Ray box. When an object would cross or trip the beam, an amplifier would be activated.

These systems were far from foolproof. Ambient light could distort results and bulbs often lost their intensity or had filaments blow out. If we rated the Detect-O-Ray purely on its steampunk value, however, it still fires on all cylinders.

Archived Reader Comments:

“I remember seeing a newer version of this technology back in the late 60s/early 70s positioned across the big front plate glass window of the J.C. Penny Outlet Store in Villa Park. I assume it was used as intrusion detection. Theirs also had a meter on it. Placing your hand across either lens would cause the meter needle to drop to zero.” –Kevin, 2019

I found one, dectet o ray, fyi , thanks for info on it.