Museum Artifacts: TootsieToy Die-Cast Cars: No. 4655 Ford Model A Coupe and No. 4629 Sedan, c. 1928

Made By: Dowst Brothers / Dowst Manufacturing Co., 4537 W. Fulton St., Chicago, IL [West Garfield Park]

Chicago-based brothers Charles and Samuel Dowst were arguably as foundational to the toy car industry as Henry Ford was to the real thing. It was work on a significantly smaller scale, obviously, but it was also refreshingly devoid of pro-Nazi sympathies.

Within a few years of the first Ford Model-T hitting the streets of Chicago in 1908, the Dowst Bros., along with Samuel’s son Theodore Dowst, seized on a simple and affordable way to miniaturize that revolutionary vehicle and those that followed it—using the latest in die-cast molding technology to create a brand new type of toy/collectible for a car-crazy country. The “TootsieToy” line, which also included everything from mini trains and planes to doll furniture and candy box prizes, would eventually become—by some estimates—the most popular toy brand of the Depression years, giving kids from any background an affordable and tangible version of an otherwise out-of-reach reality.

Within a few years of the first Ford Model-T hitting the streets of Chicago in 1908, the Dowst Bros., along with Samuel’s son Theodore Dowst, seized on a simple and affordable way to miniaturize that revolutionary vehicle and those that followed it—using the latest in die-cast molding technology to create a brand new type of toy/collectible for a car-crazy country. The “TootsieToy” line, which also included everything from mini trains and planes to doll furniture and candy box prizes, would eventually become—by some estimates—the most popular toy brand of the Depression years, giving kids from any background an affordable and tangible version of an otherwise out-of-reach reality.

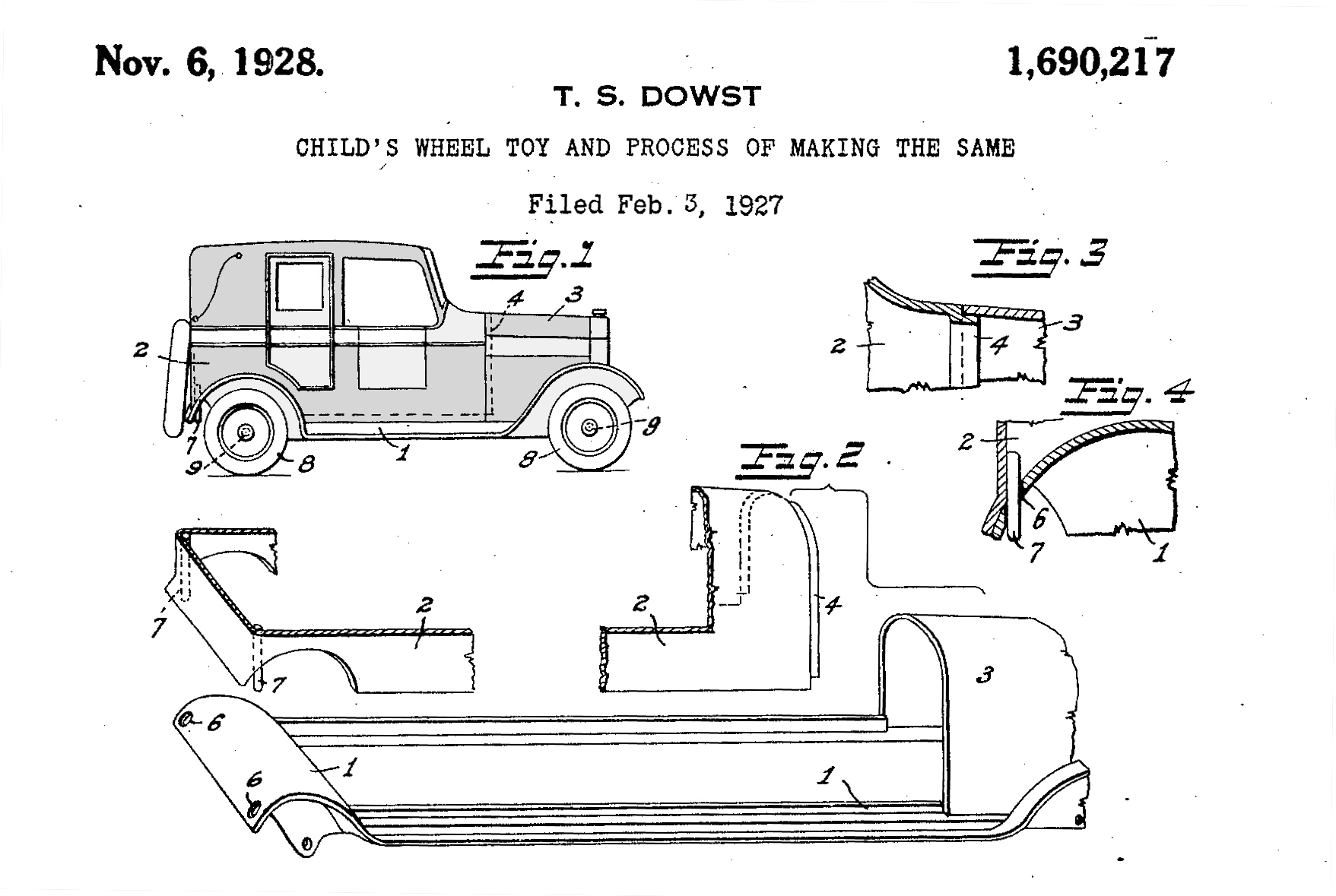

The two primary Dowst artifacts in our museum collection—a No. 4655 Coupe and a No. 4629 Sedan—were both produced from the mid 1920s to the early ’30s, and were popular models based on contemporary, real-life Ford automobiles. They were part of a wider series patented by Theodore Dowst, who started with the firm as a bookkeeper in 1906, but would gradually become an innovative gizmo designer and, eventually, company president.

[One of Theodore Dowst’s toy car patents, dating from 1928, likely applied to the mechanics used in the construction of both vintage TootsieToy vehicles from our museum collection]

[One of Theodore Dowst’s toy car patents, dating from 1928, likely applied to the mechanics used in the construction of both vintage TootsieToy vehicles from our museum collection]

It was Theodore Dowst’s own daughter Catherine, aka “Toots,” who supposedly inspired the use of the name “TootsieToy” for the company’s early pewter dollhouse furniture sets (Catherine was an illegitimate child, the result of Teddy canoodling with a Dowst Company secretary, but that’s neither here nor there).

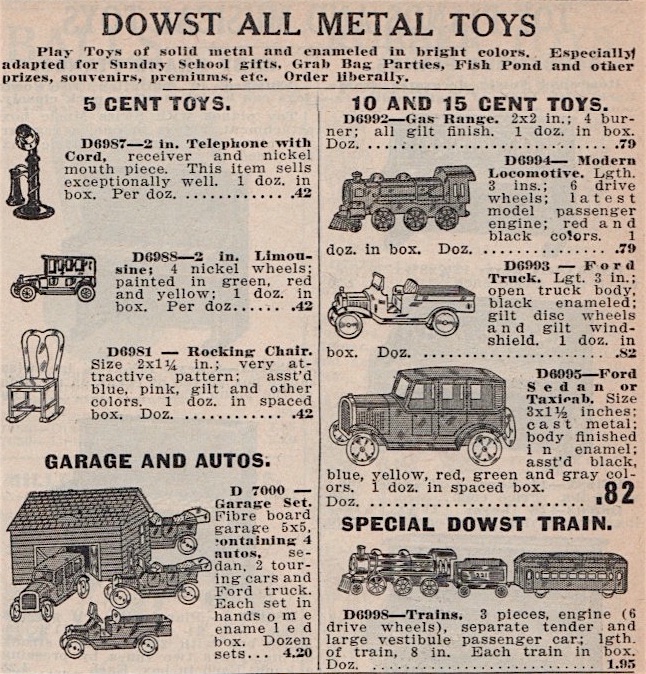

The TootsieToy brand didn’t actually become a registered trademark until 1924, and for quite a few years after, many of the company’s toy cars still carried no such identifying marks. In the public consciousness, though, the trade name quickly eclipsed the Dowst MFG Co. name, to the point where even some folks who collect old TootsieToys might have little to no knowledge of the original Chicago-based business that produced them by the millions.

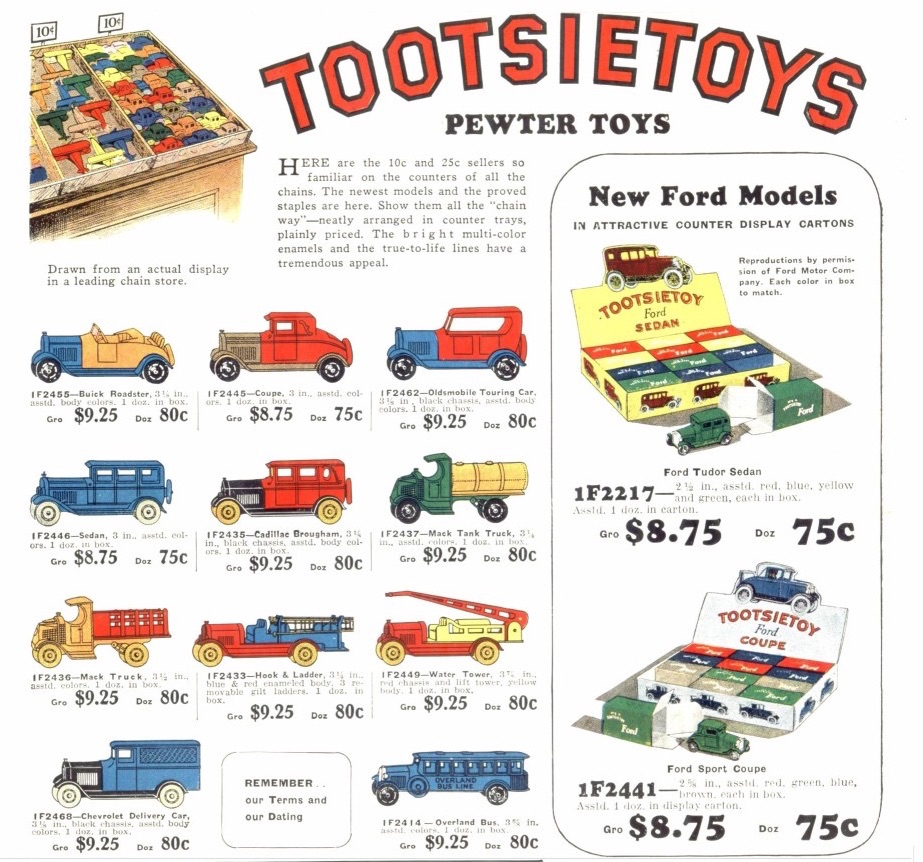

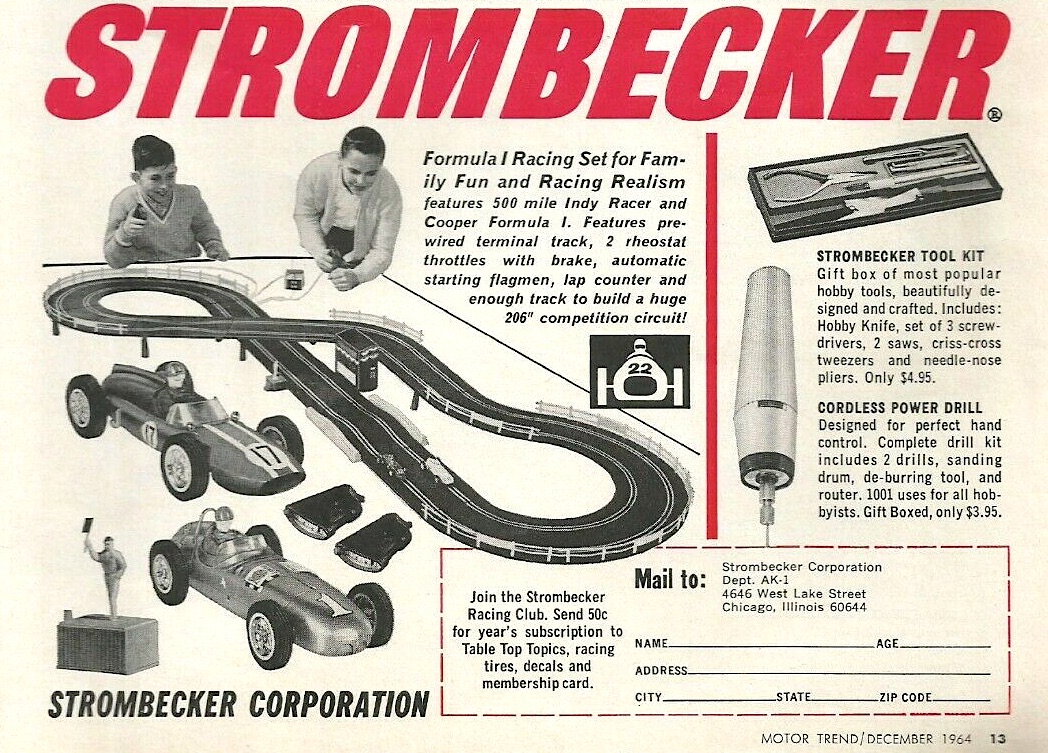

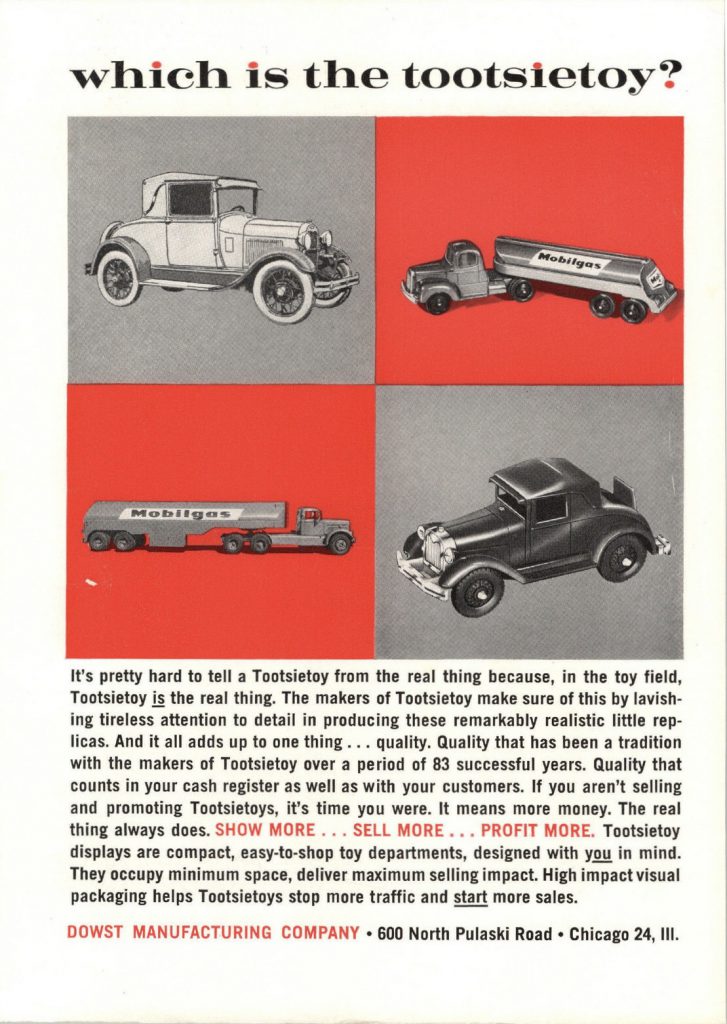

[1929 advertisement geared toward toy retailers]

[1929 advertisement geared toward toy retailers]

History of TootsieToys, Part I. Early Years (The Dowsts’ Dirty Laundry)

So where exactly did these Dowst fellas come from? Had they been whimsical toy shop owners before striking die-cast gold? Passionate automobile aficionados?

No on both counts. The original Dowst Brothers were actually devoted men of the laundry trade. Yes, that’s laundry, as in the laundering of clothes, dry cleaning, ironing, tailoring, all that jazz. Not only did they work in the industry—running their own cleaning facilities in Chicago—they were also leading voices within the high ranks of the launderers’ elite.

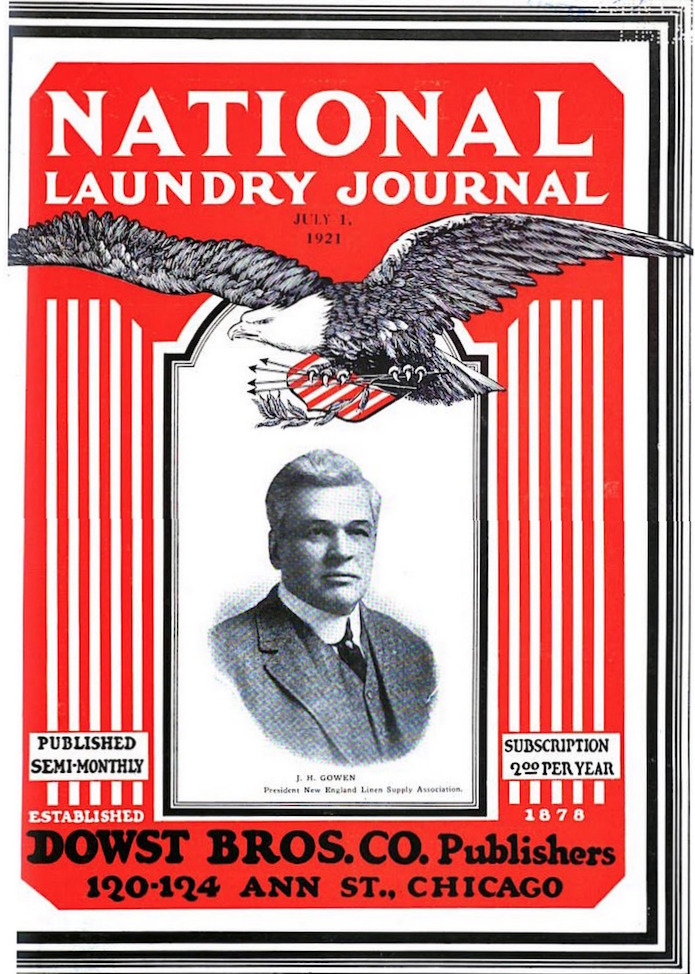

Way back in 1878, when Charles Dowst was just 26, he founded the Dowst Brothers Publishing Company, which launched the first laundry trade magazine in the world—the National Laundry Journal. It soon became the insider’s bible for sophisticated laundromat owners near and far, staying in circulation for more than 40 years.

Even the Dowsts’ unexpected foray into trinket-making never fully shifted their focus from their first love. In fact, some of the company’s earliest die-cast creations were inspired not by fancy motorcars, but by the tools of the laundering business.

As the folklore goes, younger brother Samuel Dowst was visiting the legendary 1893 Columbian Exposition when he first saw an early Linotype typesetting machine in operation and caught a jolt of inspiration. A machine that could make molds for letters could also, in theory, make other interesting shapes that might be utilized in the Dowsts’ everyday enterprise.

And so, Sam convinced Charles to invest in a casting machine of their own, and—using a zinc or tin base—they started making tiny buttons and cufflinks, among other small accessories, for their friends and business partners. These items were initially intended as promotional handouts, much like the collector cards that the National Laundry Journal was already distributing [such as the laundering cherub pictured here]. As popular demand grew, however, and as the Dowsts continued to expand the array of different tiny objects they could produce, a whole new business was born.

And so, Sam convinced Charles to invest in a casting machine of their own, and—using a zinc or tin base—they started making tiny buttons and cufflinks, among other small accessories, for their friends and business partners. These items were initially intended as promotional handouts, much like the collector cards that the National Laundry Journal was already distributing [such as the laundering cherub pictured here]. As popular demand grew, however, and as the Dowsts continued to expand the array of different tiny objects they could produce, a whole new business was born.

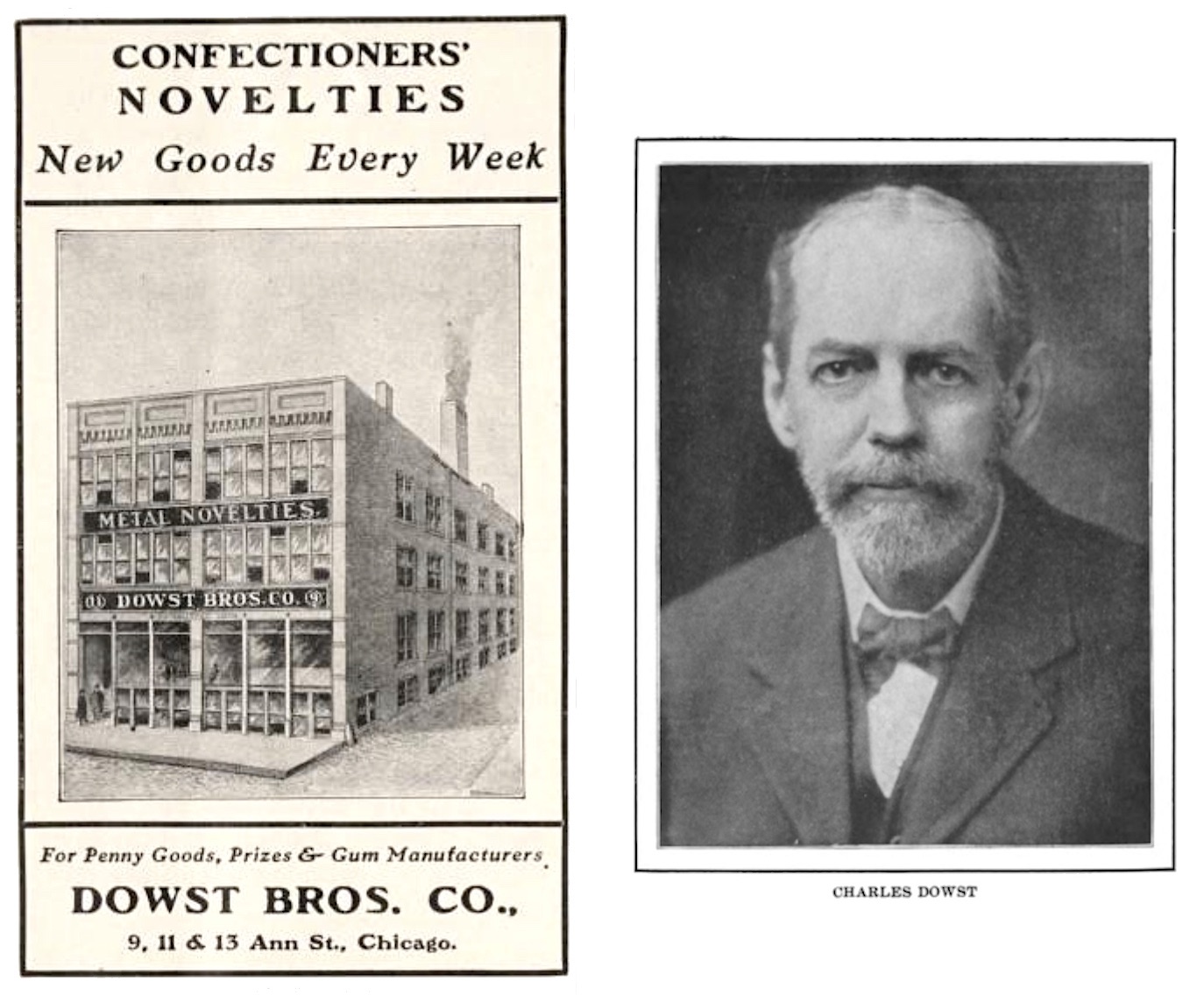

By the dawn of the 20th century, the manufacturing of “metal novelties” was now the Dowst Brothers’ central moneymaker, as they offered their Linotype services to confectioners, penny arcades, and the like. A factory at 9 Ann Street (on the location now known as 120 N. Racine Ave.) was devoted to this work, and Samuel’s son, the aforementioned Theodore, was hired to help keep the books.

From the looks of things, though, Charles Dowst—despite his booming success as a novelty / toy making mogul—never really deviated from his life’s true passion: laundry. It’s hard to find any quotes from the guy about TootsieToy or its thousands of products, but as the founder and longtime editor of the National Laundry Journal, Charles was never at a loss for words when it came to the cleaning of fabrics.

In 1919, just two months before his death at the age of 67, Charles published a compendium of articles, short stories, and poems pulled from the long history of The National Laundry Journal. He called it Second Suds Sayings, and it featured a few of his own writings, including a piece titled “Memories of Long Ago”—a mix of waxing nostalgic about laundry’s golden age and appreciating how far his industry had come.

“If some of the old timers who have passed away could come back to life and see the improvements the trade has made in the last thirty or forty years, they would think that in their day they knew nothing in regard to conducting a laundry. I recall my first visit to the ‘Quaker City,’ in the early eighties, when the proprietor of the leading laundry took great pride in showing me through his establishment, dilating on the quality of work that he turned out. It was excellent and he was justified in feeling proud of it, especially the collar and cuff work; but if he could see a late model starching machine and one of the modern dry rooms today, he would think that he was in fairyland.”

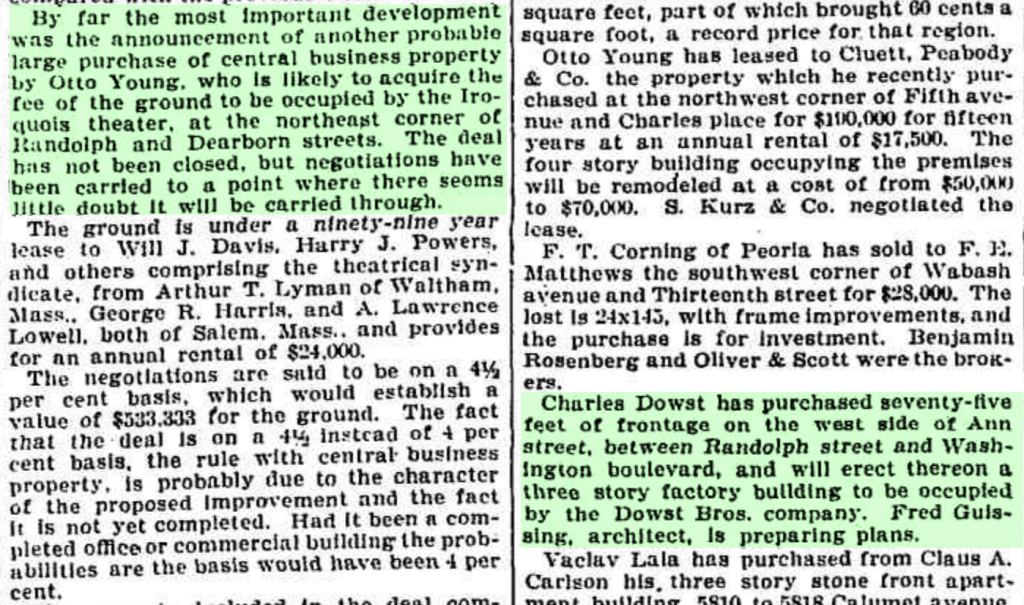

Charles Dowst was a tragic figure in some ways. In 1903, his wife Jennie was one of the 600 victims of the Iroquois Theatre disaster—the deadliest single building fire in U.S. history. Just months earlier, Charles had appeared in the business section of the Chicago Tribune, as he was completing the purchase of the land that would become the Dowst Bros. factory on Ann Street. In an eerie bit of foreshadowing, that news appeared side-by-side with another “Notable Deal of the Week”— an investor named Otto Young acquiring the real estate occupied by the soon-to-be-opened Iroquois Theatre.

[Chicago Tribune, June 28, 1903: Charles Dowst made the news alongside an Iroquois Theatre investor, months before Dowst’s wife died in a tragic fire in the same theater]

[Chicago Tribune, June 28, 1903: Charles Dowst made the news alongside an Iroquois Theatre investor, months before Dowst’s wife died in a tragic fire in the same theater]

II. Monopolizing the Business

One of the Dowsts’ early clients in Chicago, a Norwegian named Ole Odegard, was the proprietor of the Flat Iron Laundry at 3629 N. Halsted Street. Hearing of the brothers’ fancy Linotype device, he personally requested they make him a unique metal charm for his business—one he could give to patrons to earn their loyalty. The Dowsts obliged, crafting several tokens that included a flat-iron (for obvious reasons), a tiny thimble, and—for reasons lost to time—a wee Scottie dog. These tokens were eventually produced in such large numbers, and given away so liberally, that they took on a new life of their own, often used as makeshift pieces in primitive board games of the late 19th and early 20th century. You can see, naturally, where this is leading.

By 1911, Dowst Bros. had unveiled its first toy car, a generic limousine model, which was followed a few years later by their first miniaturized take on a real automobile: the Model T. It was part of an expanded campaign spearheaded by Theodore Dowst, who ultimately may have been a bigger architect of the company’s success than either his father or his uncle. Ted cast a wide net, helping to design not only mini vehicles but a whole lot of other random diecast novelties: whistles, tops, telephones, animals, etc.

In the years after World War I, with both Charles and Samuel now deceased, Theodore started working on designing and patenting new modern model cars to meet the rabid demand, with designs from Buick, Oldsmobile, Cadillac, Mack Trucks, and others joining the existing Fords. The sedan in our museum collection, which is sometimes referred to by collectors as the “Yellow Cab” (even though it came in several colors), was promoted this way in Dowst’s 1925 catalog: “A real masterpiece in miniature automobiles. We have tried to overlook no details and this Sedan is a car we are proud of. Bright color enameled finish on body and movable disc wheels in gold bronze. This number should be in every dealer’s stock.”

Around this same period, in 1926, Theodore made a bold, risky, but ultimately fruitful business decision—agreeing to sell the company to one of its longtime Chicago trinket rivals, the Cosmo MFG Co.,—makers of the miniature toys in Cracker Jack boxes. The deal played out more as a merger, as Cosmo owner Nathan Shure agreed to keep Theodore on as company president. The new combined entity would be known, interestingly enough, as the Dowst Manufacturing Company—with a new headquarters at 4537 W. Fulton Street in West Garfield Park. Ted would remain in his position until his own death in 1945, after helping turn the TootsieToy brand into a giant name in the toy market.

[Left: 4537 W. Fulton Street, the former Dowst MFG plant from the late ’20s into the 1950s, as it looks today. Right: Workers in the Dowst plant, circa 1932.]

[Left: 4537 W. Fulton Street, the former Dowst MFG plant from the late ’20s into the 1950s, as it looks today. Right: Workers in the Dowst plant, circa 1932.]

The 1930s, rather off-trend, might have been Ted Dowst’s finest era. In 1931, he was elected president of the Toy Manufacturers Association of the USA, and by 1933, he’d rolled out the influential new Graham Series of model cars, with a three-piece construction (separate body, chassis, and radiator grill castings) that was quickly adopted by international rivals like Dinky Toys and Marklin. New rubber tires replaced the all-metal wheels of the ’20s, and the introduction of the zinc alloy Zamak resulted in “lighter, sturdier castings,” according to the book TootsieToys: World’s First Diecast Models.

Then came a fortuitous association with a certain recognizable board game franchise.

[Monopoly board photo by Rich Brooks from Scarborough, ME, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

The first version of Parker Brothers’ “Monopoly,” released in 1935, had come with wooden dowels as playing pieces. But when the game was repackaged in 1937 with new metal tokens made by the Dowst MFG Co., players found the company’s familiar diecast thimble and iron now included among the avatars. To millions of Monopoly players in the decades since, these were the oddball game pieces—perceived perhaps as references to the working class in a game about wealth? But in truth, it was just a manufacturer’s inside joke—a tip of the cap to its own industrial roots.

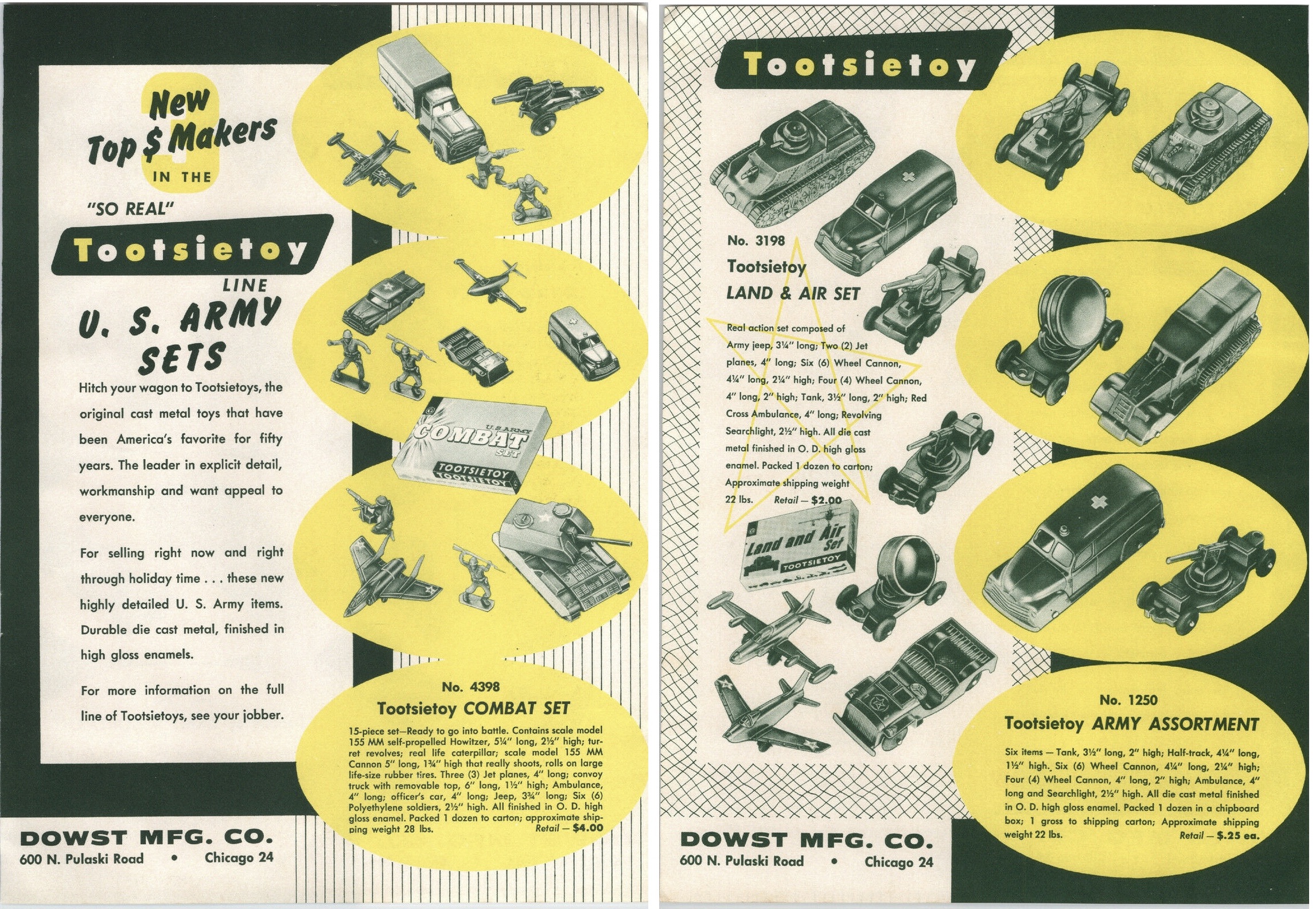

Despite the time invested in creating authentic miniatures of real vehicles, Ted Dowst may have paused at calling his company’s products genuine “models.” In 1935, he supposedly stated, “We make toys for doodling, not models for collecting.” And after shifting focus to detonator and buckle production during World War II, Dowst returned to toymaking with a renewed focus on just that—making toys, rather than painstaking scale reproductions (although the military inspired sets did reveal an extra attention to detail). In later years, the company tried to reposition itself as a quality model-maker, but collectors never really gravitated to the post-war TootsieToys the way they did to the earlier Dowst models.

[Above: 1957 advertisement for TootsieToy U.S. Army Sets. Below: The former Chicago headquarters of Dowst MFG Co. / Strombecker Corp., at 600 North Pulaski Road, as it looks today.]

[Above: 1957 advertisement for TootsieToy U.S. Army Sets. Below: The former Chicago headquarters of Dowst MFG Co. / Strombecker Corp., at 600 North Pulaski Road, as it looks today.]

III. Strombecker, a “Shure” Thing

By the mid 1950s, Dowst’s primary production plant moved to a one-story cinder-block facility at 600 N. Pulaski Rd in Humboldt Park. It wasn’t (and still isn’t) much to look at, and the corporate offices were a bit of a tight squeeze, but the building remained TootsieToys international HQ through the end of the century.

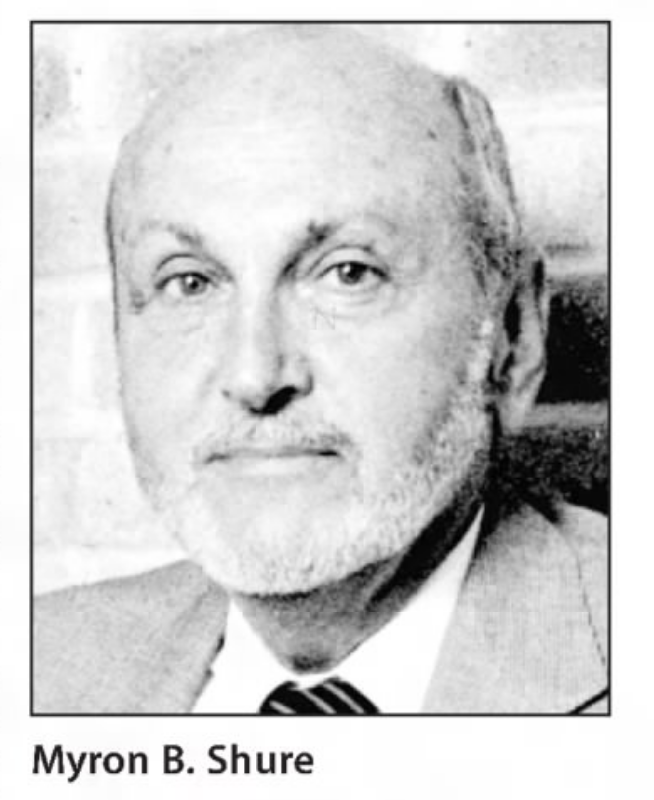

From those offices, a new company president, Myron B. Shure, along with brothers Alan and Richard (all grandsons of Cosmo MFG Co. founder Nathan Shure), helped Dowst expand into new markets, including a surging cap gun industry, as well as marbles, wood blocks, jump ropes, and anything else that cost a nickel to make and a dime to buy.

From those offices, a new company president, Myron B. Shure, along with brothers Alan and Richard (all grandsons of Cosmo MFG Co. founder Nathan Shure), helped Dowst expand into new markets, including a surging cap gun industry, as well as marbles, wood blocks, jump ropes, and anything else that cost a nickel to make and a dime to buy.

“He wanted to make toys that everybody could afford,” fourth generation president Daniel Shure later said of his father Myron. “He was proud that during times of depression, everybody could still buy for their children.”

Old fashioned as he might sound, Myron Shure (who was also a famed collector of “outsider” art) had a keen eye for emerging trends. In 1961, he acquired the plastic car manufacturer Strombeck-Becker, which was producing motorized slot cars that kids could race against one another on electrified tracks. After the purchase, Shure assigned the the Dowst MFG business a new trade name, the “Strombecker Corporation,” and for several years, the slot cars became the company’s top product.

[1964 advertisement for Strombecker slot cars. The Dowst MFG Co. acquired the Strombecker properties and became the Strombecker Corp. in 1961]

[1964 advertisement for Strombecker slot cars. The Dowst MFG Co. acquired the Strombecker properties and became the Strombecker Corp. in 1961]

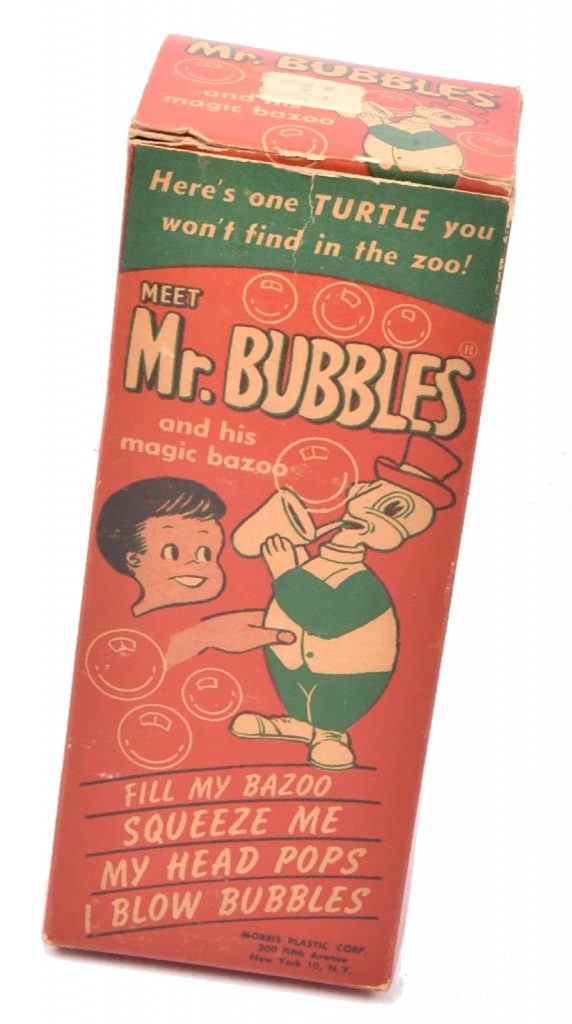

When the slot car fad tanked later in the decade, Shure kept the business afloat during some bumpy years, then made perhaps his most astute acquisition, buying Chem-Toy (makers of “Mr. Bubbles”) in 1979. Revenue increased by about 5x once the bubble-blowing toys were added to the mix.

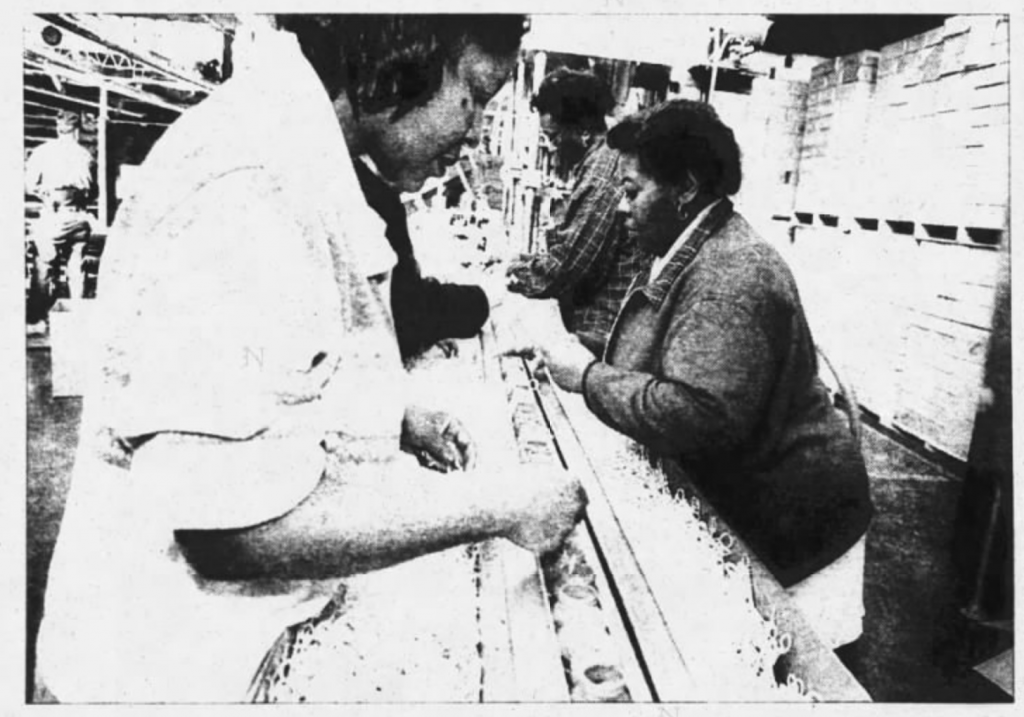

Re-adopting TootsieToys as its primary trade name, the business continued to thrive into the 1990s, with Myron Shure eventually handing off control to his own son Daniel Shure. Even as competitors like Hot Wheels dragged down their market share, the company still produced more than 40 million mini cars and trucks per year into the 1990s. By then, much of the car manufacturing had moved to China, but TootsieToy / Strombecker still had factories in Oklahoma, New York, and in its native Chicago, where the old Pulaski Road building was joined by a similarly nondescript plant at 4646 W. Lake Street. At this second location, which had formerly been home to the Strombecker slot car wing, 100 workers helped produce and package Mr. Bubbles to the tune of 50 million bottles each year.

Re-adopting TootsieToys as its primary trade name, the business continued to thrive into the 1990s, with Myron Shure eventually handing off control to his own son Daniel Shure. Even as competitors like Hot Wheels dragged down their market share, the company still produced more than 40 million mini cars and trucks per year into the 1990s. By then, much of the car manufacturing had moved to China, but TootsieToy / Strombecker still had factories in Oklahoma, New York, and in its native Chicago, where the old Pulaski Road building was joined by a similarly nondescript plant at 4646 W. Lake Street. At this second location, which had formerly been home to the Strombecker slot car wing, 100 workers helped produce and package Mr. Bubbles to the tune of 50 million bottles each year.

In 1993, the company employed 450 workers in all and profits were good, but the area around the old Humboldt Park plant was getting increasingly run down. “We’d like to stay here,” Daniel Shure told the Tribune at the time, “but it’s getting pretty dangerous. The firm has prospered here, though. It’s part of the community. Most of our workers live nearby, and it sort of fits our image. No glitz.”

[Women working on the Mr. Bubbles assembly line, 2003. Photo by Neil Schierstedt]

[Women working on the Mr. Bubbles assembly line, 2003. Photo by Neil Schierstedt]

With business slowing in the new century, Daniel Shure sold Strombecker-TootsieToys to another longtime Chicago toy maker, the Processed Plastics Company, in 2004. The union was supposed to supercharge both entities, but results proved disappointing, and within a year, Processed Plastics was liquidated. Its intellectual property, along with TootsieToys, was subsequently acquired by J. Lloyd International of Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

Sadly, that deal didn’t go so well, either. Neither the J. Lloyd nor the TootsieToy corporate websites have been updated in more than five years, and while marketing materials from a decade ago still refer to TootsieToy as “America’s Oldest Toy Company,” it’s really unclear what sort of presence they still have in America, or anywhere else. Strangely, it’s easier to research TootsieToy as it was 100 years ago, when those laundry-loving Dowsts were running the show, than it is to figure out the state or fate of the brand here in the info-rich 21st century.

If you’ve got the inside dish on TootsieToy’s current status in 2024, do let us know in the comments below. And if you work for the TootsieToy marketing department, well, you might want to start doing your job.

[1924 Dowst advertisement, before trademarking of Tootsie Toy]

[1924 Dowst advertisement, before trademarking of Tootsie Toy]

[1931 Tootsie Toy Catalog]

[1931 Tootsie Toy Catalog]

[1961 advertisement]

[1961 advertisement]

Sources:

A History of Pre-War Automotive Tootsietoys, by Clint Seeley (edited by Robert Newson)

Iroquois Theatre Disaster VictimsHistory of the Strombecker Corp. – Funding Universe

Second Suds Sayings, edited by Charles Dowst, 1919

“TootsieToy Manufacturer Promoted Affordable Fun” – Chicago Tribune, December 27, 2002

“West Side Firm Still Bubbling with Success” – Chicago Tribune, April 26, 1993

“Tiny TootsieToys Entertained Children for Decades” – Antique Week, Vol. 51, Issue 2558, Sept. 24, 2018

TootsieToys: World’s First Diecast Models, by James Wieland and Edward Force

Standard Catalog of Farm Toys: Identification and Price Guide, By Karen O’Brien, Kate Bossen

Toys and American Culture: An Encyclopedia, By Sharon M. Scott

Archived Reader Comments:

“Just goes to show u if u want to make it in America u can ” —William, 2020

” —William, 2020

“Thank you for a very informative and interesting story about the Dowst brothers and the beginnings of Tootsietoy. Now I realize I too have a direct connection to Dowst in a way. My Grandmother was supposed to go to the Iroquois Theater that night. Her father had promised to take her there to celebrate her tenth Birthday. She got sick that day and they didn’t go.” —Tim Musselman, 2019

Looking in a about tootsie carrousel – any details on history of it

Me and my husband were wondering if we could buy tootsie toys straight out from your website.

Sorry, this is a museum about Chicago companies of the past (including TootsieToy). We don’t sell any products. — Made in Chicago Museum

I have about 27 army vechiles made by toosie toys in the USA would like to know more about them .my partner who would have been 92 got them as a boy any info would be nice

Thanks a lot for the article. I recently unearthed (literally) a little Triumph TR3 made by Tootsietoys some time in the mid sixties from a garden in California. I was curious about it since I’m from the UK and wasn’t familiar with the Brand. You filled in all the gaps and way more. The Monopoly token era was particularly interesting. So thank you again for your research and excellent writing.

Does anyone have any pictures of the number 187 mack transport truck 1941 is the pin offset or not and are the wheels rubber with hubcaps or on rims I have a complete one but not sure of the truck 🤔

My mother worked at the T-T plant at 700 n. Pulaski in the early 1950s

In 1959 I got a job at the N. SURE mail order warehouse just on the south side of the Tootsie Toy building.

I absolutely love everything I have read about Tootsie toys I have some .I love any old toys ,mostly smalls .I am 80yrs. and I still look for toys today it never gets old for me.Thanks for letting me get my thoughts out.Yours truly Don Welch 9/14/23

Tootsietoy Strombecker was a great place to work and my 1st job me and mother and brother worked there in the 70s.

Greetings from Cypress, Texas. My name is Dan Martin and I have an old Ambulance that I think that y’all might have built. I would like to send y’all a picture of the toy Ambulance so that y’all might tell me the age and also the approximate value of the Ambulance. Would you please send me a telephone number, so that I may send you a photo ?

I have some tootsie toys that I cannot find online anywhere. Of course, I’m wondering they’re worth. Would love to send a picture and you could let me know what you think.

Hello

I’m Don

I really love tootsie toys

I was thinking if I started a tootsie toy dealership store with the real ones

Maybe the company might come out of the woodwork an go after me an I could buy the company. Your thoughts

I have a Buick Sedanette that has wood tires. Is it true that during the war Tootsietoy used wood instead of rubber on some of their diecast vehicles.

I have a TOOTSIETOY FIAT ABARTH RED DIECAST CAR FOUND IN SOIL WHILE METAL DETECTING.

I WOULD LIKE TO KNOW THE DATE OF THE FIAT MODEL, AND ALSO THE DATE THAT TOOTSIETOY MANUFACTURED THIS MINI TOY CAR.

IT IS RED , AND HAS EXHAUSED PIPES ON THE BACK.

THANK YOU.

LORRAINE

My Great, Grandmother retired from there in the mid 70’s Louise Smith. She started there in the 50’s 600 N. Pulaski Rd.

Thank you for this article. One of my neighbors growing up was a salesman for Strombecker. He kept the entire neighborhood supplied with complimentary cap guns, TootsieToy cars and bubbles. Our Cub Scout troop even took a field trip to the old Strombecker factory in the city to watch ladies assemble the toy cars. It was a great Chicago company!

I tracked J. Lloyd International and found it is still a registered corporation in Iowa. The address is : J. Lloyd International, 6738 6th Ave. SW, Cedar Rapids, IA 52404

They filed a Biennial report in 2020 and probably don’t need to file again until 2022. I have a cap gun just like a Tootsietoy version that was made in China in the 2000s, but it no longer has Tootsietoy or anything on it but Made in China. Suspect J. Lloyd International sold it to someone who is now making generic Tootsietoy-like items in China. Maybe Lloyd gets a royalty or is tied in with a Chinese manufacturer.

Found an old metal diecast dump truck that has Tootsietoy number one Chicago 24 like to try and find some little bit of history on it as it’s the one meeting as the first one it’s got a yellow front and a dream that all tires are there still

Please, have you any information about terms of likely agreement between Tootsietoy and an english company named Die Casting Machine Tool (DCMT) which produced a first line of die cast cars evidently derived from Tootsietoy 200 series ? Were the original Dowst machine and/or moulds included in the agreement ? Or did DCMT, like other european companies, “pirated” the original technology ?

Regards. JPL

Thank you for all that you do to preserve, curate, and educate enthusiasts of this unique art form. Your published articles featuring historical advertising has enabled me to identify and date many early pieces in my collection. I’m grateful for your continuing effort in this area.

Thank you, Grant Lenox, Marquette, Michigan

Unfortunately, two among the two best print sources on Tootsietoy vehicles are not referenced here: David Richter’s “Tootsietoys” and Wieland and Force’s “Tootsietoys: America’s First Diecast Models.” Between the two of them, one can find a pretty comprehensive set of color pics of most pre- and post-war models. Shure’s “no glitz” intentions were the company’s undoing starting in the 60s; while Marx and other toy manufacturers were starting to explore finely detailed, but inexpensive, replica toy vehicles, Tootsietoy kept churning out generic vehicles that were no doubt cheaper than those of competitors, but entirely undesirable next to Mattel (Hot Wheels) or Tyco (Matchbox).

By the late 00’s, I had more than 200 Tootsietoy vehicles. I’m not quite as rabid as I was when I started collecting them seriously in the 90s, but I will still pick up something I don’t have, and I still have the first couple in my collection, inherited from my older brothers in the early 60s. Thanks for an interesting article.

Great article, thanks.