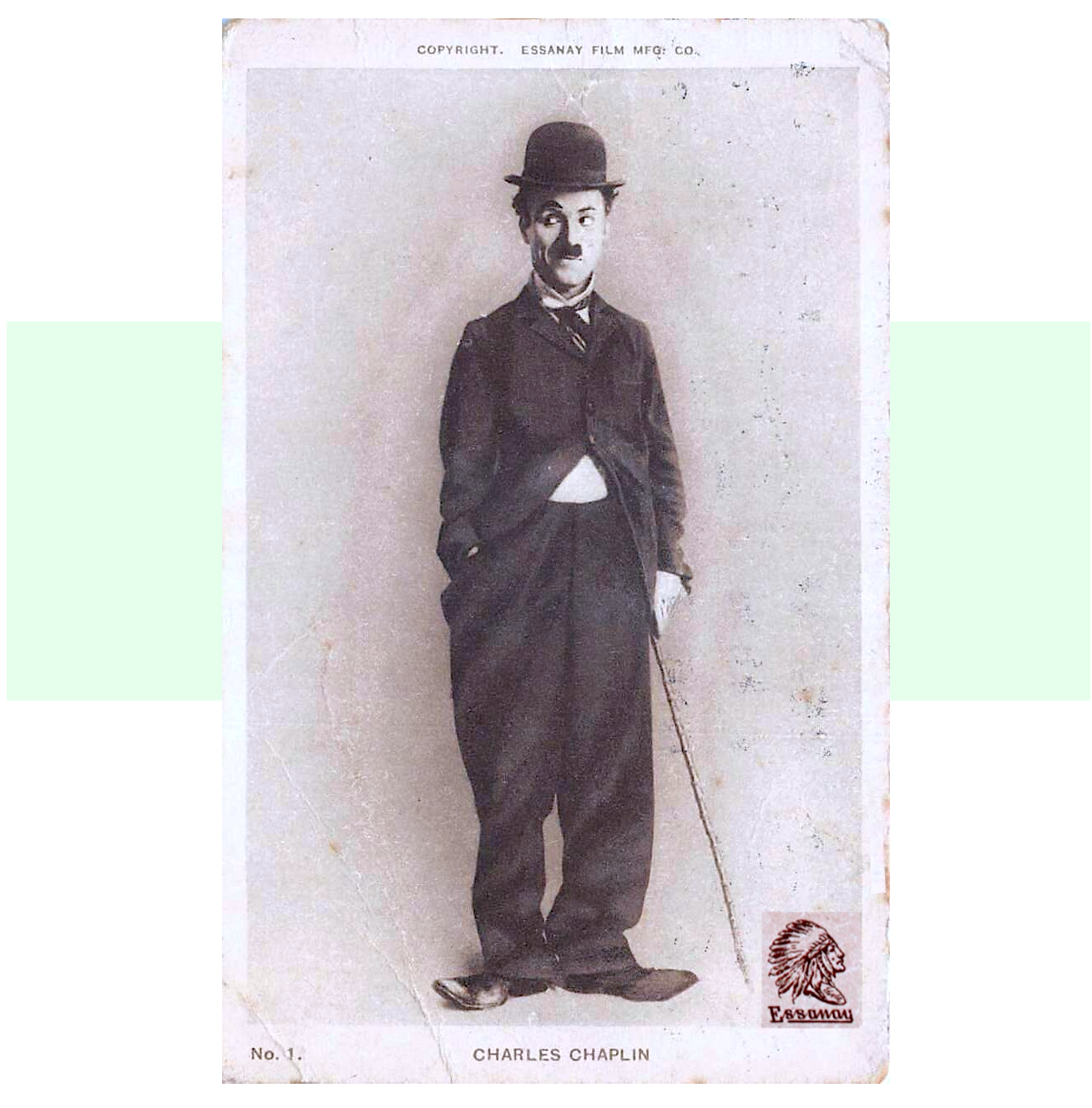

Museum Artifact: Charlie Chaplin Collectible Postcard, Essanay No. 1 , 1915

Made By: Essanay Film MFG Co. / Essanay Studios, 1333 W. Argyle St., Chicago, IL [Uptown]

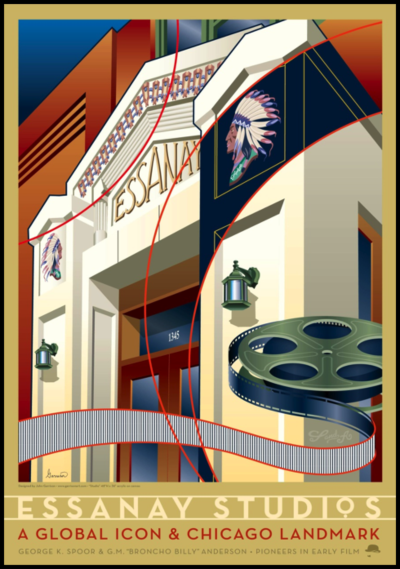

On a quiet, tree-lined street in Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood, just north of the old St. Boniface Cemetery and around the corner from the Green Mill jazz club and the long-shuttered Uptown Theatre (once one of the world’s great movie palaces), you’ll find a two-story red-brick building with a highly conspicuous white terra-cotta front entrance. Cracked and faded by more than 100 Chicago winters, the doorway still features its original ornamentation—highlighted by two Indian heads in profile, adorned with feathered headdresses and engaged in a never-ending staring contest. Between them, in escalating gold lettering, is the peculiar word “ESSANAY.”

It’s virtually impossible to walk down West Argyle Street without noticing it. And yet, having lived directly next-door to the Essanay building myself for several years, I can confirm that for most passersby, the mystery and history of the place elicits little more than a brief eyebrow raise. Yes, there’s a “Chicago Landmark” plaque right there by the entrance, explaining that this is “the most important structure connected to the city’s role in the history of motion pictures.” But if you walk further down to the corner of Argyle and Clark Street, there’s also Chicago’s first legal pot dispensary and a really good hot dog place! Who can keep up with all Uptown has to offer?

One thing you learn when you’re sharing an alleyway with a defunct silent film studio (now owned by a community college) is that the ghosts of the past are both inherently invisible and potentially everywhere. In other words, while the vast majority of Chicagoans have never heard of the Essanay Film MFG Company or its pivotal contributions to the movie biz, those who DO know the story are all too eager to pepper the facts with hyperbole and mythology. And no figure from the studio’s past is more ripe for mythologizing than the larger-than-life “Little Tramp” himself, Charlie Chaplin.

If you’re ever apartment hunting in Uptown, there’s a 50/50 chance that your estate agent will woo you with a tale of how—during his days in the employ of Essanay Studios—“Charlie Chaplin lived in this very building!” And no, it doesn’t matter which building you’re looking at.

If you’re ever apartment hunting in Uptown, there’s a 50/50 chance that your estate agent will woo you with a tale of how—during his days in the employ of Essanay Studios—“Charlie Chaplin lived in this very building!” And no, it doesn’t matter which building you’re looking at.

Charlie also supposedly frequented a good dozen or so of the establishments over on Broadway, even the ones that weren’t built yet. And then there’s that quirky abandoned theater further north at 5757 N. Ridge Avenue—the purple one— which was supposedly constructed to be Chaplin’s personal movie house in 1918—even though Charlie was already long gone to California by that point.

Clearly, when you’ve spent some time as the single most famous person on the face of the earth, every one of your footsteps can leave behind a bread crumb for your countless admirers, present and future. And sometimes, the wind can spread those imaginary bread crumbs to the seven seas, or Great Lakes, as the case may be.

The reality is that Chaplin’s time as a Chicagoan—while important and often overlooked by his own biographers—was still more like an artistic one-night stand than a lengthy romance. He was here, in total, for about two months, starting around Christmas in 1914 through February of 1915. Of the 15 films he made during his one-year contract with Essanay Studios, only the very first one, His New Job, was actually filmed on Argyle Street. The rest were made at Essanay’s second location in Niles, California, after a frustrated Charlie demanded and received a change of scenery.

That abrupt exit, along with an oft-referenced L.A. Times quote in which Chaplin supposedly assessed his Windy City experience as merely “too damn cold,” paint an unromantic picture.

On further inspection, however, it becomes quite evident that Chicago left a pretty powerful impression on the young actor, after all, albeit a complicated one.

“Chicago was attractive in its ugliness, grim and begrimed,” he wrote in his autobiography some 50 years later. “[This was] a city that still had the spirit of frontier days, a thriving, heroic metropolis of ‘smoke and steel,’ as Carl Sandburg says. The vast plains approaching it are, I imagine, similar to the Russian steppes. It had a fierce pioneer gaiety that enlivened the senses, yet underlying it throbbed masculine loneliness.” Wow!

Chaplin had made his first visit to Chicago in 1910 on the Vaudeville circuit, and enjoyed his time chasing around the local burlesque girls from his seedy hotel on Wabash Ave. Now, five years later, he was the highest paid actor in the world, stolen away from Mack Sennett’s Keystone Studios by Essanay’s promise of a then jaw-dropping $1,250 per week contract with a $10,000 signing bonus. In today’s money, that’s about a $2 million deal.

With his income, talent, and popularity all reaching a harmonic crescendo, Chaplin’s arrival in Chicago also became his arrival into true, uncharted super-stardom—even though that 1990s bio-pic with Robert Downey, Jr. ignored the whole chapter completely. Typical coastal bias.

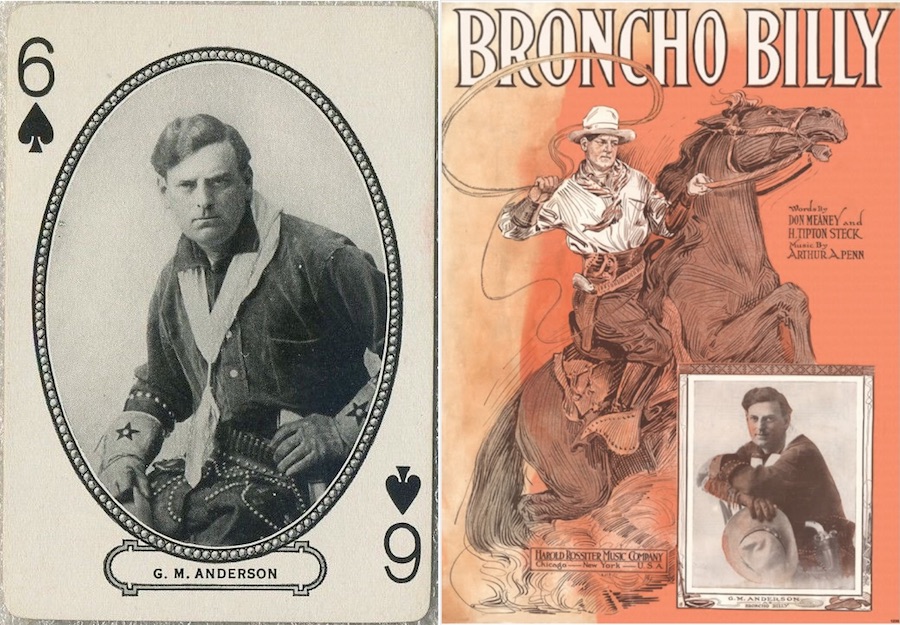

Speaking of coastal biases, Essanay tends to get the shaft a bit when it comes to explorations of vital cinema history. The company started in Chicago in 1907, founded by the local inventor and businessman George Spoor and the popular actor Gilbert M. “Broncho Billy” Anderson—one of the stars of 1903’s The Great Train Robbery.

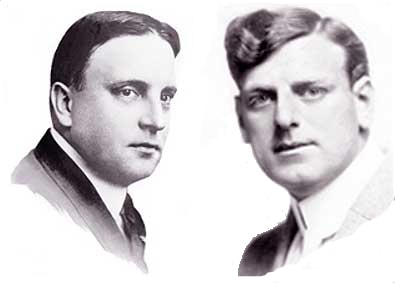

[Essanay founders George Spoor (left) and G.M. Anderson]

Spoor was the “S,” Anderson was the “A,” and their combined powers (“S and A”) gave Chicago its second great motion picture studio, the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company. With the Selig Polyscope Co. (founded 1896) also in Chicago, the Windy City was as much at the forefront of early movie making as New York or New Jersey, and certainly way ahead of an obscure little village called Hollywoodland.

G. M. Anderson—who was doing double duty as a co-owner of the company and its biggest box office draw—was the one who recognized Chaplin’s value as a free agent signing. On the other end, Spoor—who got into the business by patenting a new type of movie projector (two of his original employees were the future founders of Bell & Howell)—couldn’t believe ANY performer was worth the kind of dough they’d just thrown at this goofy Brit with the oversized shoes. Spoor’s philosophy on making pictures was much more practical and systematic. It’s why Essanay called itself a “Film Manufacturing Company” instead of a “studio.” To the non-performing crew members who made their daily living in the lighting, camera, and props departments on Argyle Street, that distinction was maybe even appreciated. This was its own brand of Chicago factory life, after all—not all glitz and glamour.

G. M. Anderson—who was doing double duty as a co-owner of the company and its biggest box office draw—was the one who recognized Chaplin’s value as a free agent signing. On the other end, Spoor—who got into the business by patenting a new type of movie projector (two of his original employees were the future founders of Bell & Howell)—couldn’t believe ANY performer was worth the kind of dough they’d just thrown at this goofy Brit with the oversized shoes. Spoor’s philosophy on making pictures was much more practical and systematic. It’s why Essanay called itself a “Film Manufacturing Company” instead of a “studio.” To the non-performing crew members who made their daily living in the lighting, camera, and props departments on Argyle Street, that distinction was maybe even appreciated. This was its own brand of Chicago factory life, after all—not all glitz and glamour.

“Everybody wants to write about those stars,” an older, slightly bitter Spoor recalled in a 1947 interview. “It’s the growth of the industry that’s important. Why, some of our actors were people we hired on the street wherever we happened to be making pictures that day.”

For his part, Chaplin’s view of his new bosses basically mirrored their opinions of him. He liked Broncho Billy—arguably America’s first movie Western star—noting that he had “a certain kind of charm.” Charlie rode the train from California to Chicago with Anderson, and even stayed with the cowboy’s family at their Uptown apartment during part of that winter (the address was 1027 W. Lawrence Ave, but the original building isn’t there, so don’t believe what you hear!).

George Spoor, by contrast, became one of Charlie’s many foes in his journey to total creative freedom. Right from the beginning, there were problems, and it didn’t have anything to do with the Chicago weather.

“I had almost finished my first picture, which was called His New Job,” Chaplin wrote, “and two weeks had elapsed and still no Mr. Spoor had shown up. Having received neither the bonus nor my salary, I was contemptuous. ‘Where is Mr. Spoor?’ I demanded at the front office. They were embarrassed and could give no satisfactory explanation. I made no effort to hide my contempt and asked if he always conducted his business affairs in this way.”

Spoor [pictured], supposedly and improbably, claimed he’d never heard of Chaplin before Anderson signed him, and thus was incredulous about the whole thing in his own right. But it didn’t take long to see the flood of media attention generated by Chaplin’s arrival in Chicago, and Spoor was eventually moved to appease his new star—while also monetizing him to the max for the studio’s own gain.

Spoor [pictured], supposedly and improbably, claimed he’d never heard of Chaplin before Anderson signed him, and thus was incredulous about the whole thing in his own right. But it didn’t take long to see the flood of media attention generated by Chaplin’s arrival in Chicago, and Spoor was eventually moved to appease his new star—while also monetizing him to the max for the studio’s own gain.

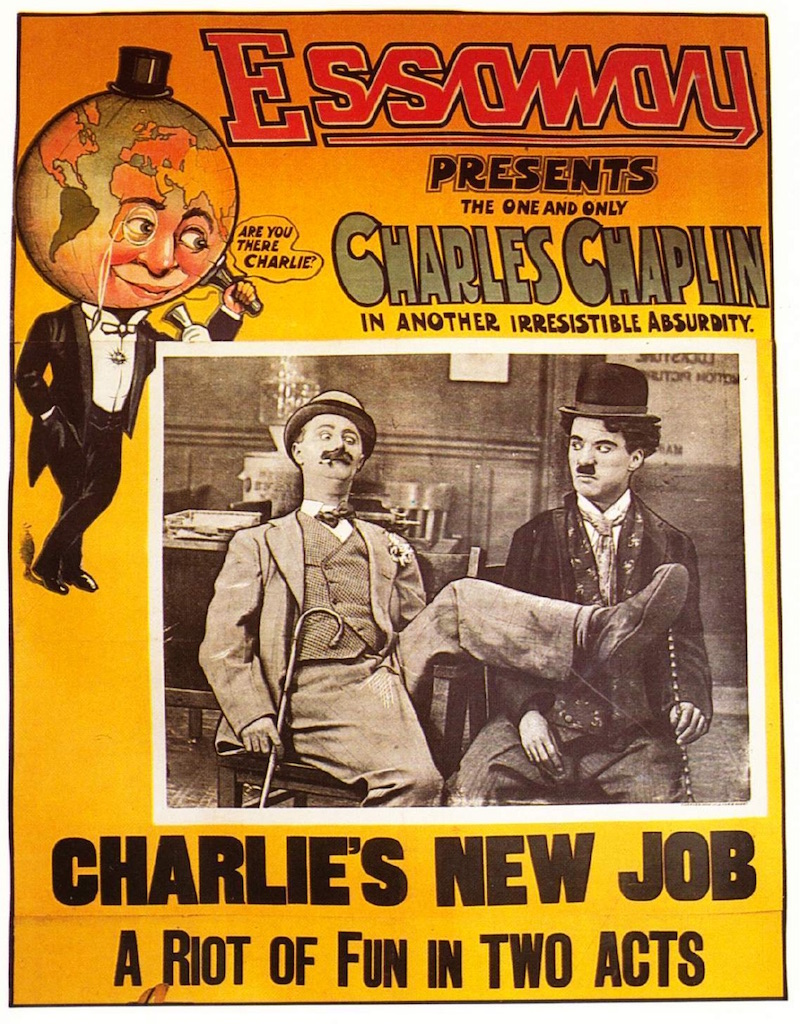

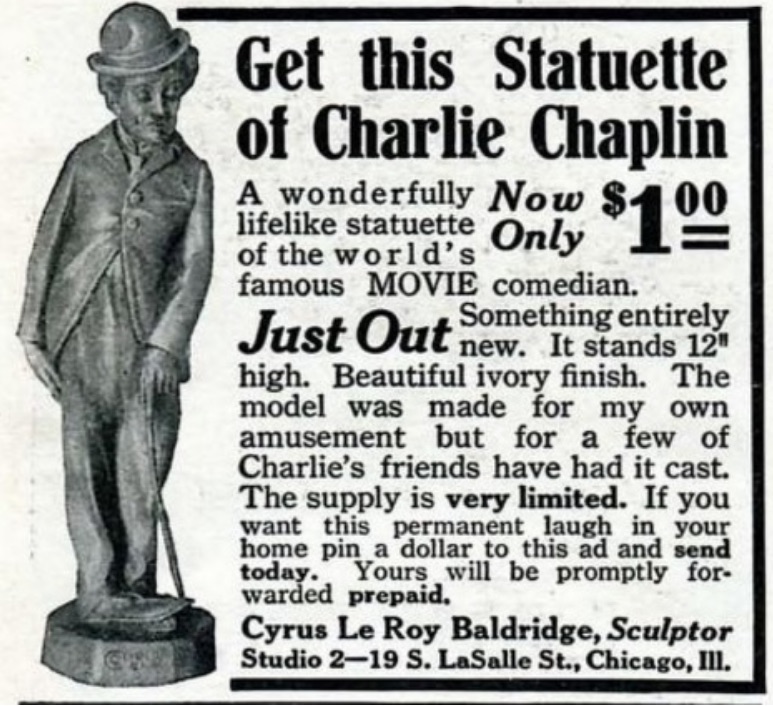

This meant not only trying to keep Chaplin on a tight leash—cranking out two-reel comedy gold—but also capitalizing on his skyrocketing popularity by selling the Chaplin image that Essanay, in theory, rightfully owned.

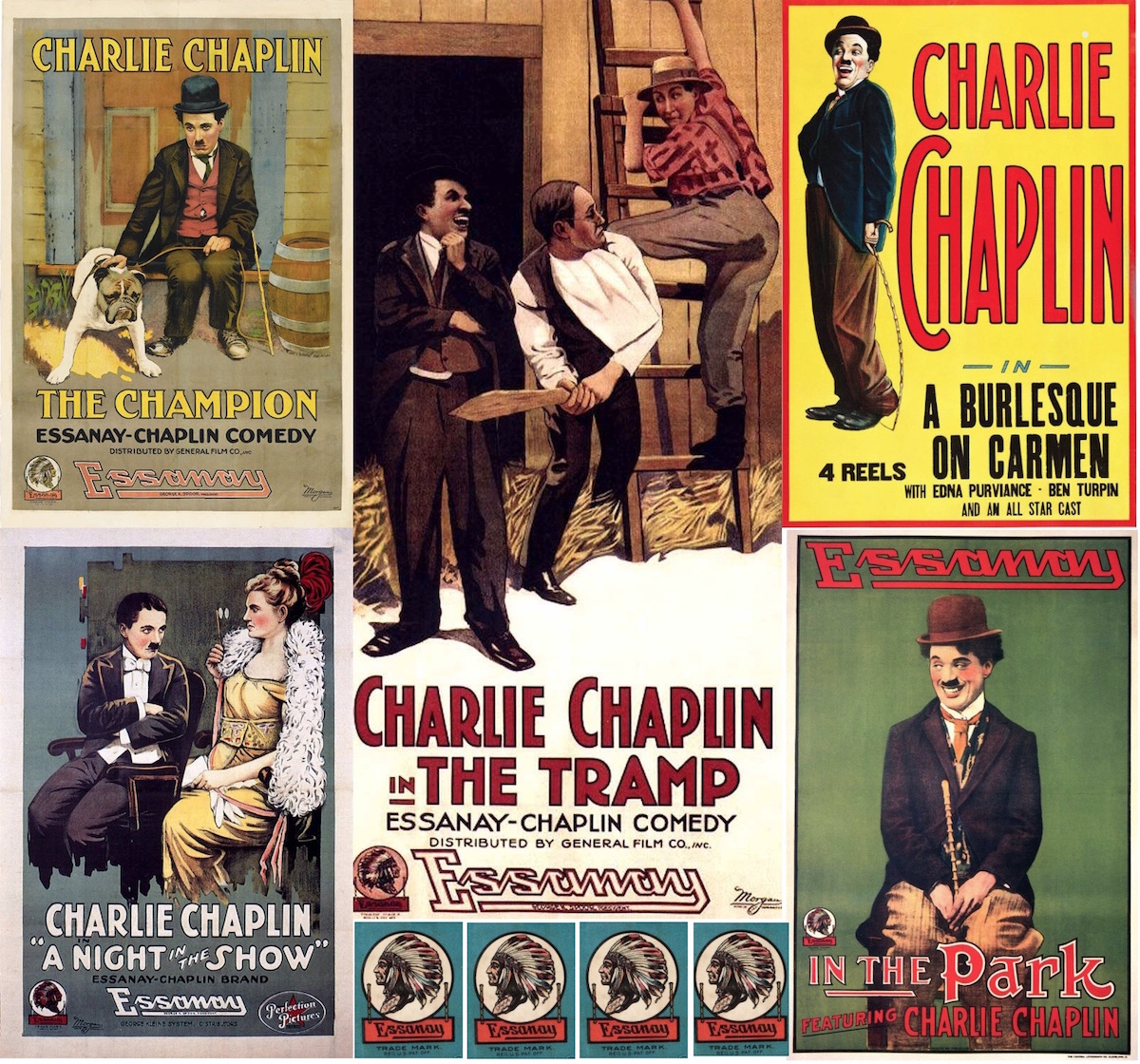

Chaplin look-a-like events were held across the country; merchandise was generated; huge promotional campaigns were launched; and official studio postcards like the one in our collection—a very popular form of cinema collectable at the time—were produced, showcasing the Tramp in his various Essanay roles. Our postcard, listed as “No. 1,” presents Charles Chaplin in his iconic Tramp uniform and pose—a human logo.

At the same time all that was happening, the ever-astute Chaplin—caught up in the tidal wave of his own success—turned to his manager (his brother Sydney) to try and corner their own share of the international phenomenon known as “Chaplinitis.” They started the Charlie Chaplin Advertising Service Company while he was still at Essanay, but both the actor and his studio found the market simply flooded beyond their control.

In 1915, Sydney Chaplin received a letter from James Pershing, the man he’d put in charge of the Advertising Service Co.

In 1915, Sydney Chaplin received a letter from James Pershing, the man he’d put in charge of the Advertising Service Co.

“We find that things pertaining to royalties are in a very chaotic state,” Pershing wrote. “There seems to be hundreds of people making different things under the name of Charlie Chaplin. First we have to find out where they are, what they are making, and are notifying them as fast as possible to stop or arrange with us for royalties, which is about all we can do.”

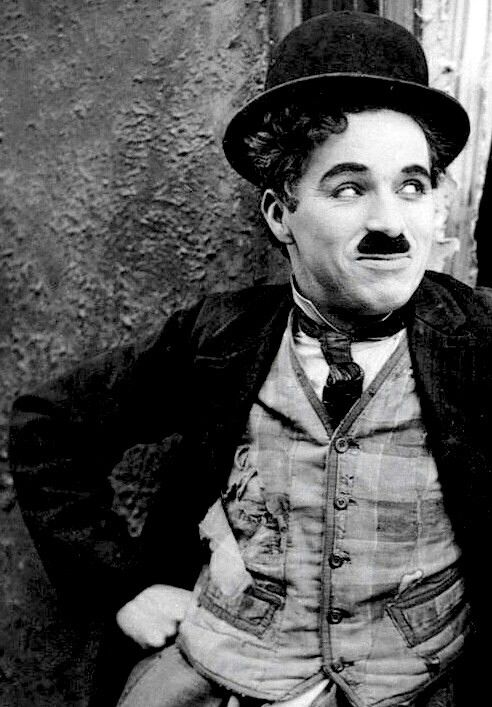

Perhaps the strangest thing about Chaplin’s explosive fame was that—despite having the most recognizable face on the planet—his face was also not entirely his own. The real Charles Chaplin—sans mustache, baggy pants, and cane—was just another fresh-faced young man riding the L train and going to jazz clubs. It was reverse incognito in a way. Before filming His New Job, Charlie even supposedly went shopping on State Street to buy a new set of the Tramp’s signature attire, since he’d left the original clothes at Keystone.

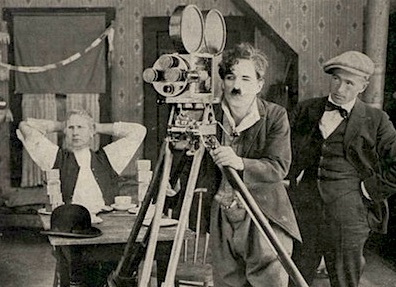

[Chaplin (center) with Essanay cohorts Francis X. Bushman (left) and G.M. Anderson]

That lone Chaplin-Chicago film, His New Job—an obvious self-referential farce set behind the scenes of a fictional film shoot—wasn’t an all-time classic, but at the time, it was still widely reviewed as one of the funniest comedic films ever released. In many respects it continued the slapstick style Charlie had established at Keystone, but in some ways, it also set him on course for what would be one of his most pivotal years as a performer and filmmaker.

For his later Essanay movies like “A Jitney Elopement,” “The Tramp,” and “Champion,” he was given much more power, and subsequently experimented with how silent comedy worked, moving beyond physical gags into smart, surprisingly emotional territory.

“Chaplin’s acting, even in those days, fascinated everyone,” former Essanay script writer H. Tipton Steck recalled in 1940. “He was so dynamic, yet subtle. Whenever he was doing a scene, the other members of the cast would behave as though they were hypnotized. Everybody stood still, and watched him. Even the stagehands would leave their work and gather around. It became a standard joke in the company that ‘this fellow Chaplin had better be dropped. He disrupts the whole organization with his antics.’”

[Chaplin made 15 pictures at Essanay, though a couple were pieced together from cut footage after his contract ended]

Unfortunately for George Spoor and Gilbert Anderson, the fate of Charlie Chaplin wouldn’t be theirs to decide. Despite huge box office sales and consistently ace reviews for his work out in Niles, Charlie was ready to jump ship from the penny-pinching Essanay boys at the end of his one-year contract, and plenty of studios were chomping at the bit to steal him away.

“Francis X. Bushman, then a great star with Essanay, sensed my dislike of the place,” Chaplin wrote. “[He said] ‘whatever you think about the studio, it is just the antithesis’; but it wasn’t. I didn’t like the studio and I didn’t like the word ‘antithesis.’

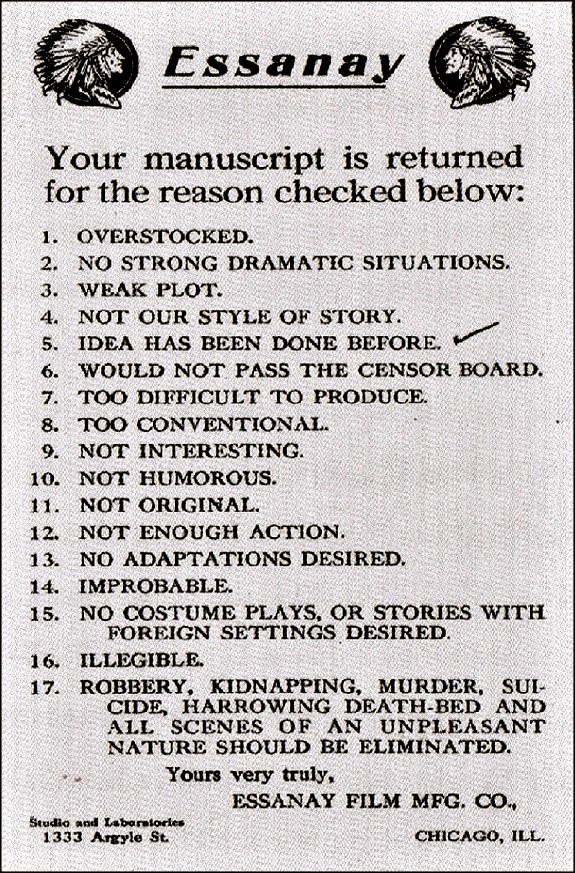

“Circumstances went from bad to worse. When I wanted to see my rushes, they ran the original negative to save the expense of the positive print. This horrified me. And when I demanded that they should make a positive print, they reacted as though I wanted to bankrupt them. They were smug and self-satisfied. Having been one of the first to enter the film business, and being protected by patent rights which gave them a monopoly [Essanay was part of a controversial patents trust started by Thomas Edison], their last consideration was the making of good pictures. And although other companies were challenging their patent rights and making better films, Essanay still went smugly on, dealing out scenarios [scripts] like playing cards every morning.”

“Circumstances went from bad to worse. When I wanted to see my rushes, they ran the original negative to save the expense of the positive print. This horrified me. And when I demanded that they should make a positive print, they reacted as though I wanted to bankrupt them. They were smug and self-satisfied. Having been one of the first to enter the film business, and being protected by patent rights which gave them a monopoly [Essanay was part of a controversial patents trust started by Thomas Edison], their last consideration was the making of good pictures. And although other companies were challenging their patent rights and making better films, Essanay still went smugly on, dealing out scenarios [scripts] like playing cards every morning.”

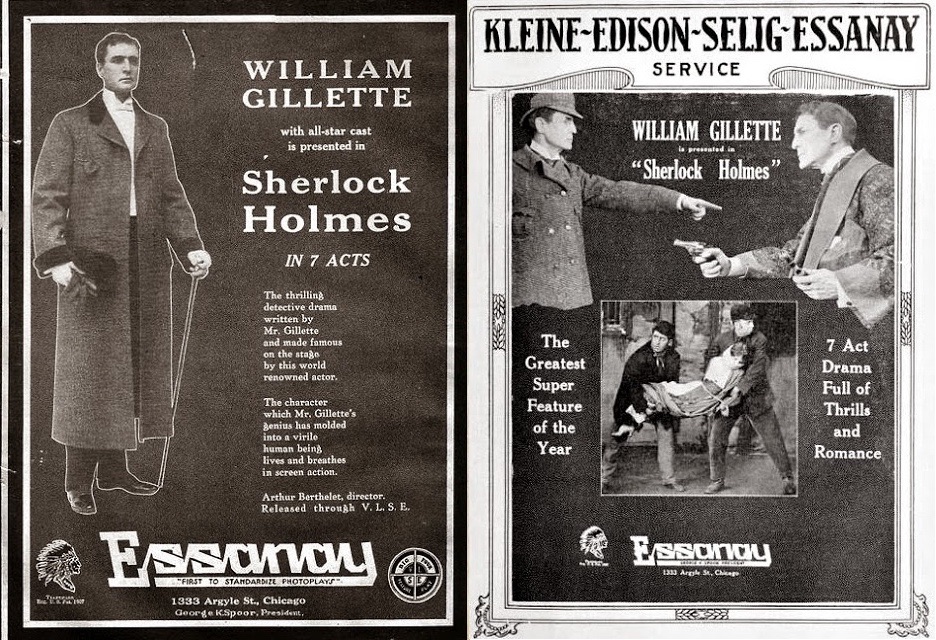

Of course, Charles Chaplin was never short on smugness himself. Long before he came to town, and at least for a little while after he left, Essanay was doing quite alright for itself commercially and creatively. They produced as many as 2,000 films over a little more than a decade, including some of the first great westerns with Broncho Billy; the first ever film adaptation of Sherlock Holmes; great comedies with underappreciated talents like Chaplin’s His New Job co-star Ben Turpin; and other popular flicks that launched the careers of stars like Francis X. Bushman, Edward Arnold, and Wallace Beery. Essanay also introduced the world to a young Chicago-born actress who had made her very first appearance, uncredited, as a stenographer in His New Job. Her name was Gloria Swanson.

[Above: Gloria Swanson’s uncredited cameo behind Chaplin and Charlotte Mineau in His New Job, filmed in Chicago in 1915]

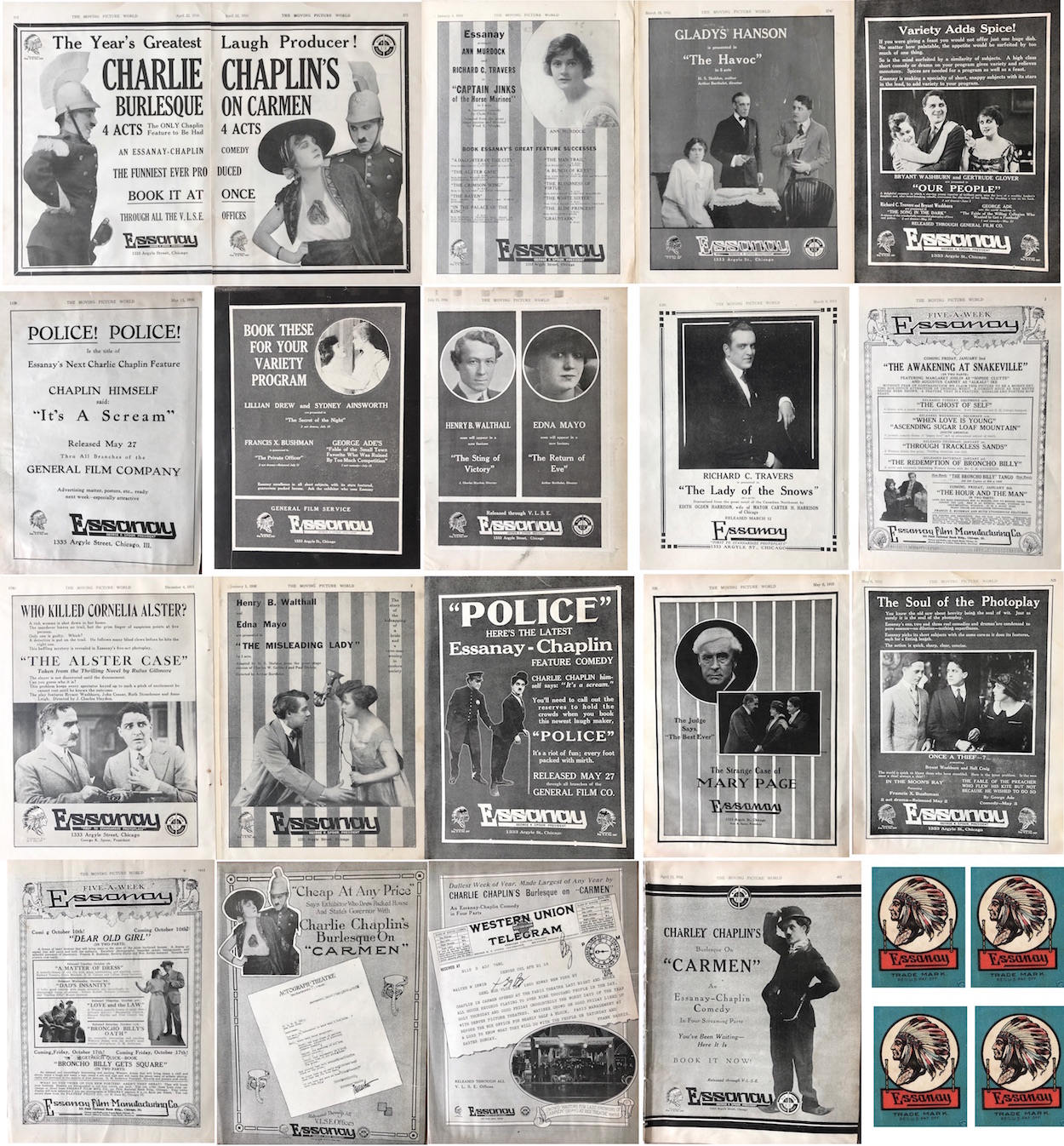

[Below: A sampling of Essanay’s broad range of non-Chaplin films]

For all his complaining about Essanay, Chaplin gained a lot of from the experience, too, including several co-stars he’d take with him to his next few studios—including his leading lady for many years, Edna Purviance.

If Chaplin’s salary at Essanay had been impressive, though, his new deal with Mutual Pictures for 1916 was the final stamp on his swank-ass legend. It was reported as $10,000 per week plus a $150,000 signing bonus—demolishing the Essanay numbers and, apparently, the salary of any other paid employee in America. His train journey from California to New York to sign the papers became tabloid fodder, as crowds gathered to follow his victory march across the country.

“From Kansas City to Chicago people were again standing at railroad junctions and in fields,” Chaplin remembered, “waving as the train swept by. . . . In Chicago, where it was necessary to change trains and stations, crowds lined the exit and hoorayed me into a limousine. I was driven to the Blackstone Hotel and given a suite of rooms to rest in before embarking for New York.

“I wanted to enjoy it all without reservation, but I kept thinking the world had gone crazy! If a few slapstick comedies could arouse such excitement, was there not something bogus about all celebrity? I had always thought I would like the public’s attention, and here it was—paradoxically isolating me with a depressing sense of loneliness.”

Charlie certainly wasn’t the only sad fellow in Chicago by this point. Broncho Billy Anderson, seeing the writing on the wall, sold his shares in Essanay to George Spoor. The movement of the industry to the West Coast and the government crackdown on the Edison patent gang were the final nails in the coffin. Essanay shut down its Chicago operations in 1917. The factory, as George Spoor saw it, was closed.

“The place was a madhouse,” Spoor later said. “I tried a number of general managers with no success. I found I was running a high class school for directors and actors. I’d make stars out of them and other producers would offer them more money. I had to meet those offers or lose the stars. Had I met all the offers, I would have gone broke myself, constantly doubling salaries. So I locked up the place and took a good, long rest.”

Spoor continued to work on the technical end of things, helping to develop an early 3-D system and a 65mm widescreen format. He continued to live in an apartment at 908 W. Argyle Street into his golden years, and had his bitterness finally rewarded with an honorary Oscar in 1948. Broncho Billy continued playing the occasional cowboy, and also produced films for the likes of Stan Laurel. He got his own honorary Oscar in 1958. And Chaplin, of course, well . . . he became the main thing people talk about in regards to a Chicago movie studio that he spent little more than a fortnight working in. Oh, and he got his pat-on-the-back Academy Award, too, though it took far, far too long (1972).

[The vintage Essanay ads above, all part of the Made in Chicago Museum collection, came from the pages of Moving Picture World magazine between 1915 and 1916]

The Essanay building itself actually remained in use for many years as a film studio—albeit for less exciting things like independent industrial films and local access TV. Today, it’s the campus for St. Augustine College, which still maintains one of the original Essanay sound stages (silent stages?) as the “Charlie Chaplin Auditorium.”

In 2013, a campaign was launched by St. Augustine College to raise money to restore the Essanay building’s terra-cotta entrance, and to transform the Chaplin Auditorium into a proper museum to Chicago’s cinema history.

In 2013, a campaign was launched by St. Augustine College to raise money to restore the Essanay building’s terra-cotta entrance, and to transform the Chaplin Auditorium into a proper museum to Chicago’s cinema history.

With a target goal of $250,000 total, the group started an Indiegogo page hoping to raise $100,000 from the public. They also hosted several fundraising events. Representatives tried to explain all of the history mentioned above, and they distributed posters of the Essanay Studio in its vibrant, re-imagined glory. I joined in the cause myself, donating some scratch and spreading the worst as best I could. In the end, however—perhaps entirely due to my own failings as a human being—the project only raised $23,000, and the whole effort was abandoned completely by 2014.

Essanay remains one of the few silent film studios in the world that’s still standing, even if it’s doing so very silently.

[I had some fun recreating a shot at 1345 W. Argyle St., 1914 vs. 2014]

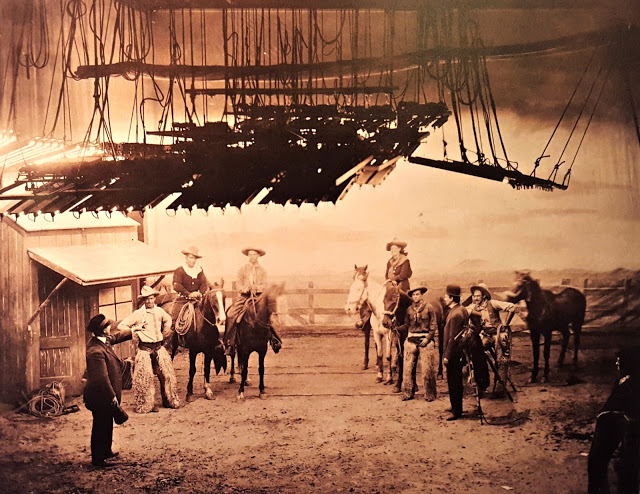

[Shooting a Broncho Billy western on the Chicago lot, c. 1912]

[Cameramen on the Essanay backlot]

[The first major Sherlock Holmes was shot by Essanay in Chicago, starring longtime Sherlock stage actor William Gillette. The film was lost for decades but recently unearthed.]

[A script rejection notice from the Essanay office]

[Sit back and enjoy Charlie Chaplin’s one and only Chicago film, “His New Job,” from 1915]

Sources:

My Autobiography, by Charles Chaplin, 1964

“St. Augustine Calls Off Essanay Fundraising Program” – Reel Chicago, 2013

“His New Job: Chaplin’s First Days at Essanay” – Flicker Alley, 2015

“Reel Chicago” – Chicago Magazine, 2007

Chaplin: The Tramp’s Odyssey, by Simon Louvish, 2009

Archived Reader Comments:

“Totally left hand but when David Bowie was in Chicago for – https://www.chicagoreader.com/Bleader/archives/2014/09/29/the-time-david-bowie-called-chicago-home he was boinking Oona O’Neill, Chaplins 3rd wife. What goes around comes around as they say.” —Marc, 2019

“Great website. Just wanted to pass on that before World War I my Grandfather Herbert ‘Chub’ Gustafson worked for Essanay in the Set Design Department. He was drafted in 1918 and fought with the Illinois National Guard 33rd Division in France where he was awarded a Silver Star and Purple Heart. When he came back in 1918 after the War, Essanay was closed and he ended up getting a job with Western Electric and worked at first in the Hawthorne Plant and was ultimately transferred to the Kearney Plant in NJ where he retired in 1959. I remember as a child that he had all sorts of photos and other memorabilia from Essanay, but after he and my Grandmother died, I think one of my Aunts had everything.” –Mark Wood, 2019

“That’s very interesting, Mark. I don’t think I’ve encountered anyone with a direct family connection to an Essanay employee. Any chance some of those photos and memorabilia have survived somewhere in the family? They could be of great interest to Chicago collections like ours and certainly to film historians. Thanks for sharing your grandfather’s story!” —Made In Chicago Museum

“ Great article! Wish the Essanay fundraiser had been a success. I simply think it just needed more time to get rolling.” —Byron Caloz, 2018

Great article! Wish the Essanay fundraiser had been a success. I simply think it just needed more time to get rolling.” —Byron Caloz, 2018

“Thank you for all your research, organization and web publications.

” —John Gilinsky, 2018

” —John Gilinsky, 2018

Hello – I have an etching / engraving that is marked in pencil on the bottom “Portrait of the Artist” “Asan” (sp) “Essanay” ” then an illegible first name followed by “Murray”. I am wondering if I could send you a copy and you could identify who the person in the picture is supposed to be.

Thank you,

Terry Walters

While married, I recall my husband and his friend going to the Essany Studio and purchasing “microfis film”. I’m not sure what else they purchased. The time frame would be around the late “70’s and early 80’s”.