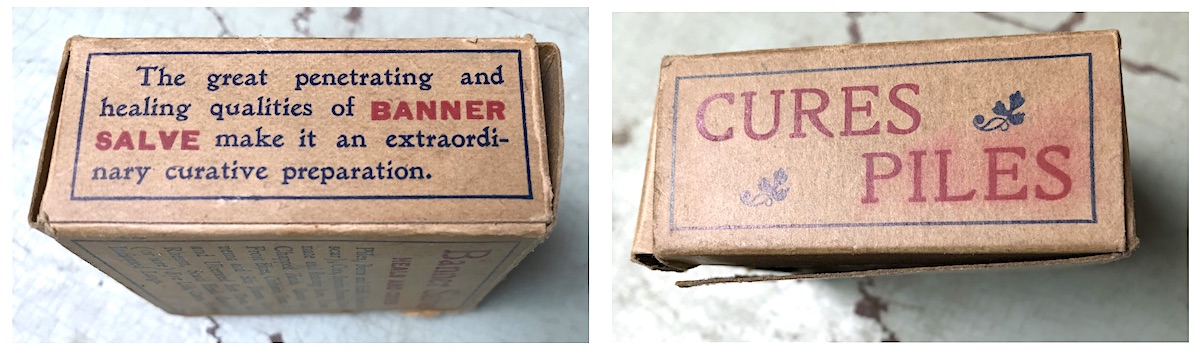

Museum Artifact: Foley Banner Salve, c. 1900s

Made By: Foley & Co., 319-333 W. Ohio St., Chicago, IL [River North]

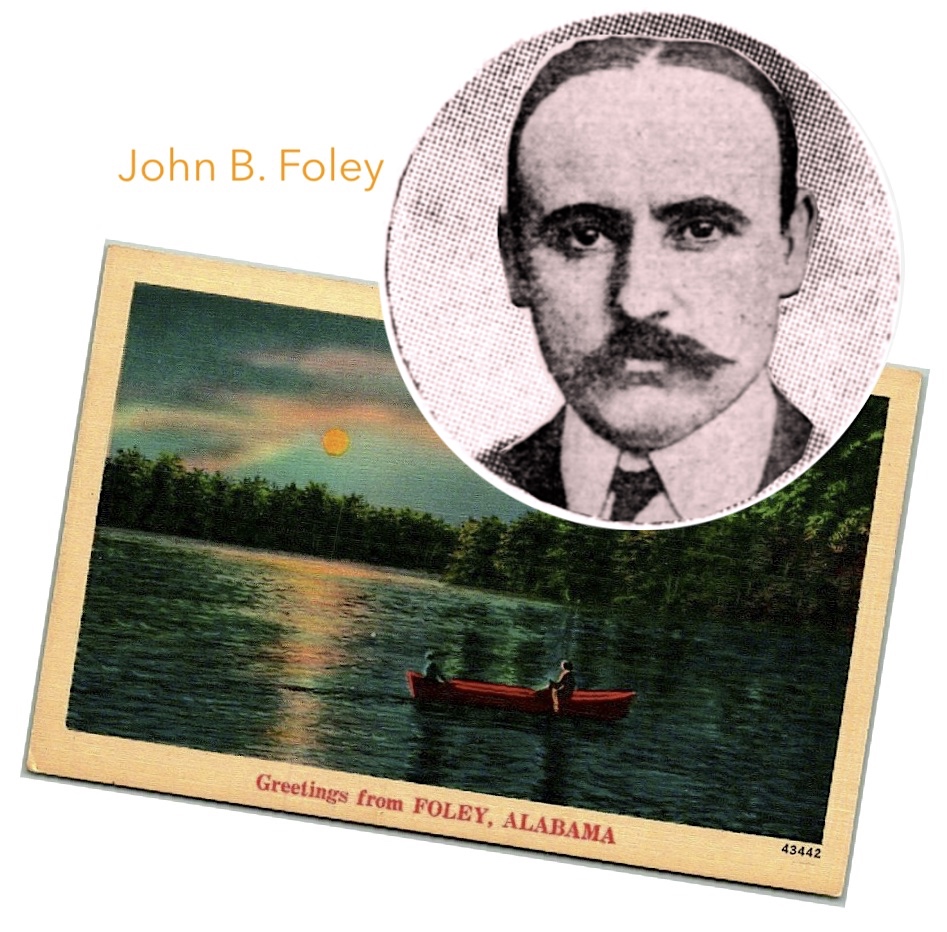

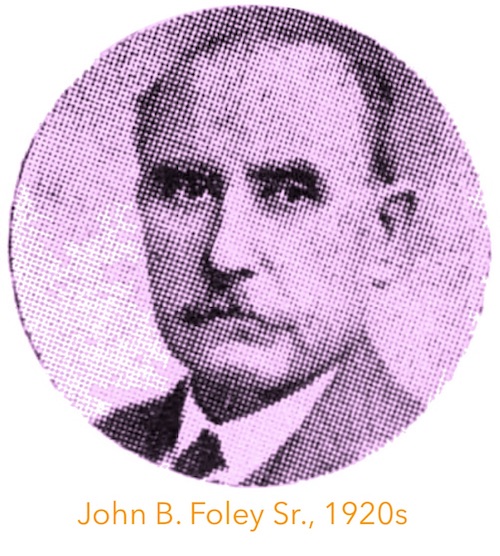

John Burton Foley was one the many opportunistic men of the Gilded Age to find his fortune in proprietary medicines; aka, patent drugs—the “cure-alls” that required no scientific substantiation to sell to the public. The Made In Chicago Museum has tracked several similar quackery kingpins from this same era, including E. C. DeWitt, William Rood, and (arguably) Wallace Abbott. But while each of these men banked massive profits from the proliferation of glorified placebos, John Foley was quite unique in at least one respect—he’s the only one who got an entire town named after him.

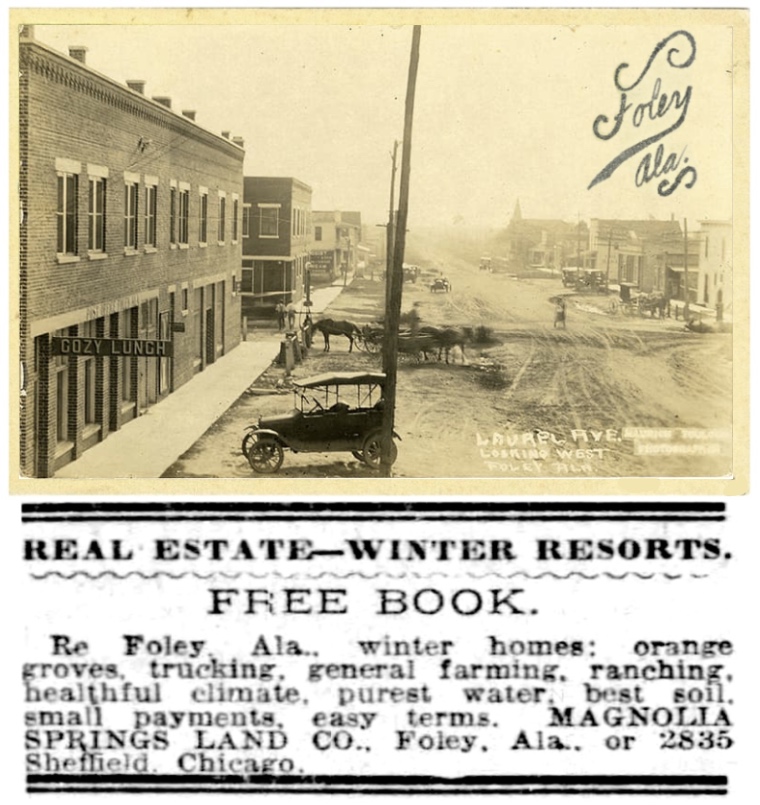

In 1902, less than fifteen years after establishing his drug manufacturing business in Chicago, Foley purchased a substantial amount of forest land in Baldwin County, Alabama, where he went about financing a railroad line, parks, and other facilities. The brand new community that sprang up from the effort—incorporated in 1915 as Foley, Alabama—is still going strong today, population 14,000-ish. The town is, in a way, a living monument to John Foley’s better angels, although he never permanently left Chicago to live there himself.

In 1902, less than fifteen years after establishing his drug manufacturing business in Chicago, Foley purchased a substantial amount of forest land in Baldwin County, Alabama, where he went about financing a railroad line, parks, and other facilities. The brand new community that sprang up from the effort—incorporated in 1915 as Foley, Alabama—is still going strong today, population 14,000-ish. The town is, in a way, a living monument to John Foley’s better angels, although he never permanently left Chicago to live there himself.

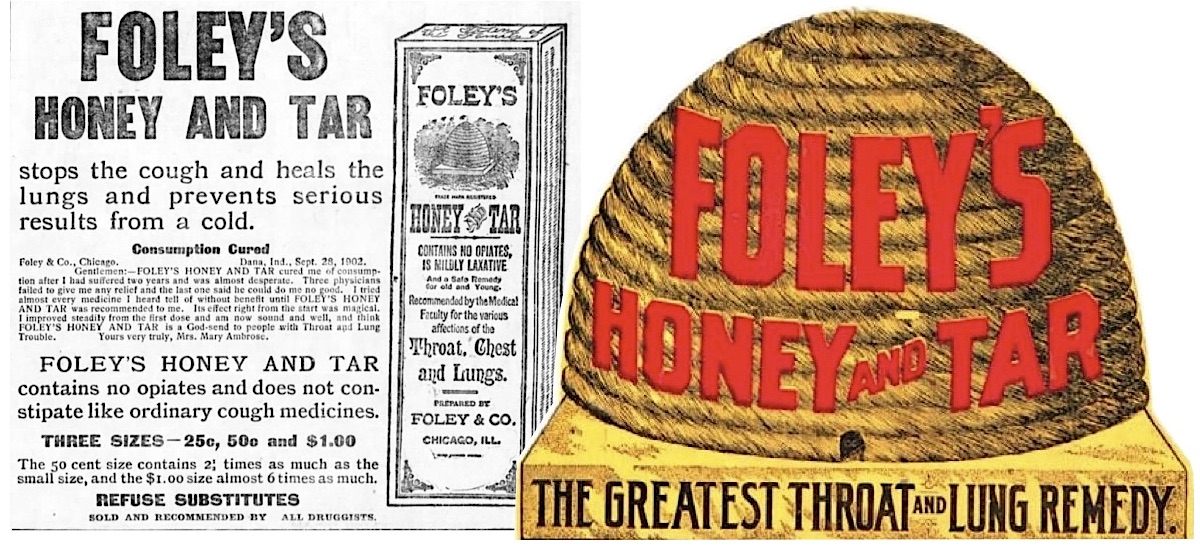

It wasn’t until 1957, in fact—over 30 years after Foley’s death—that his son J. B. Foley, Jr. finally decided to relocate the family drug business from Chicago to the friendlier confines of their namesake Alabama hamlet. By then, Foley & Company was already long removed from its early 20th century heyday, when proprietary products like “Foley’s Kidney Cure” and “Foley’s Honey and Tar Cough Syrup” were recognized household names.

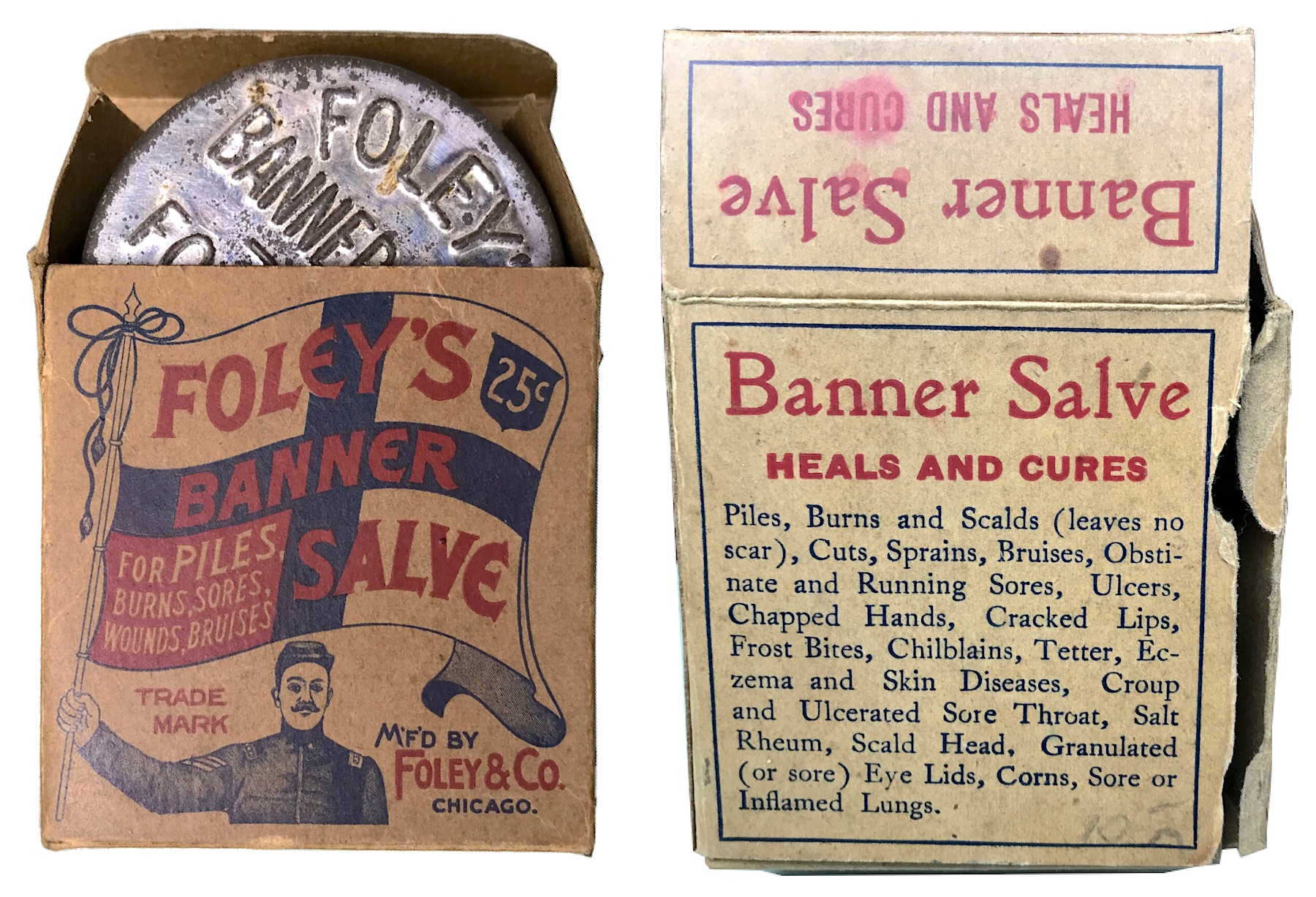

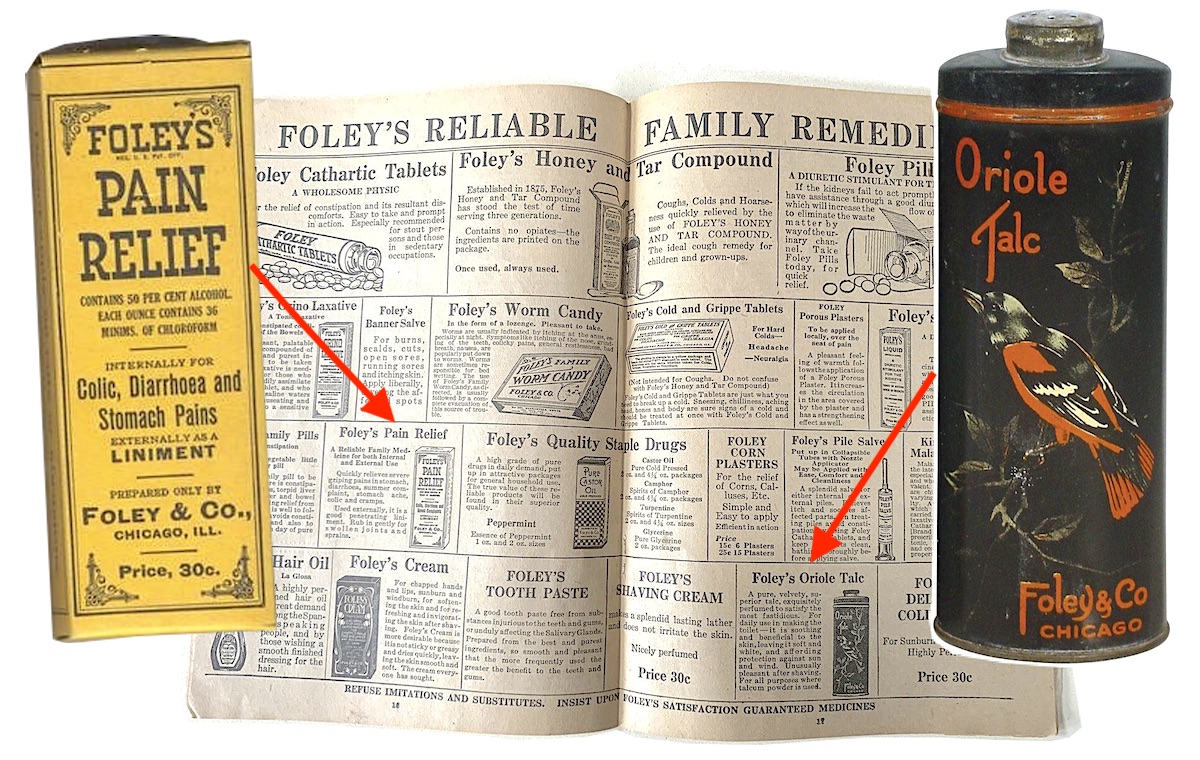

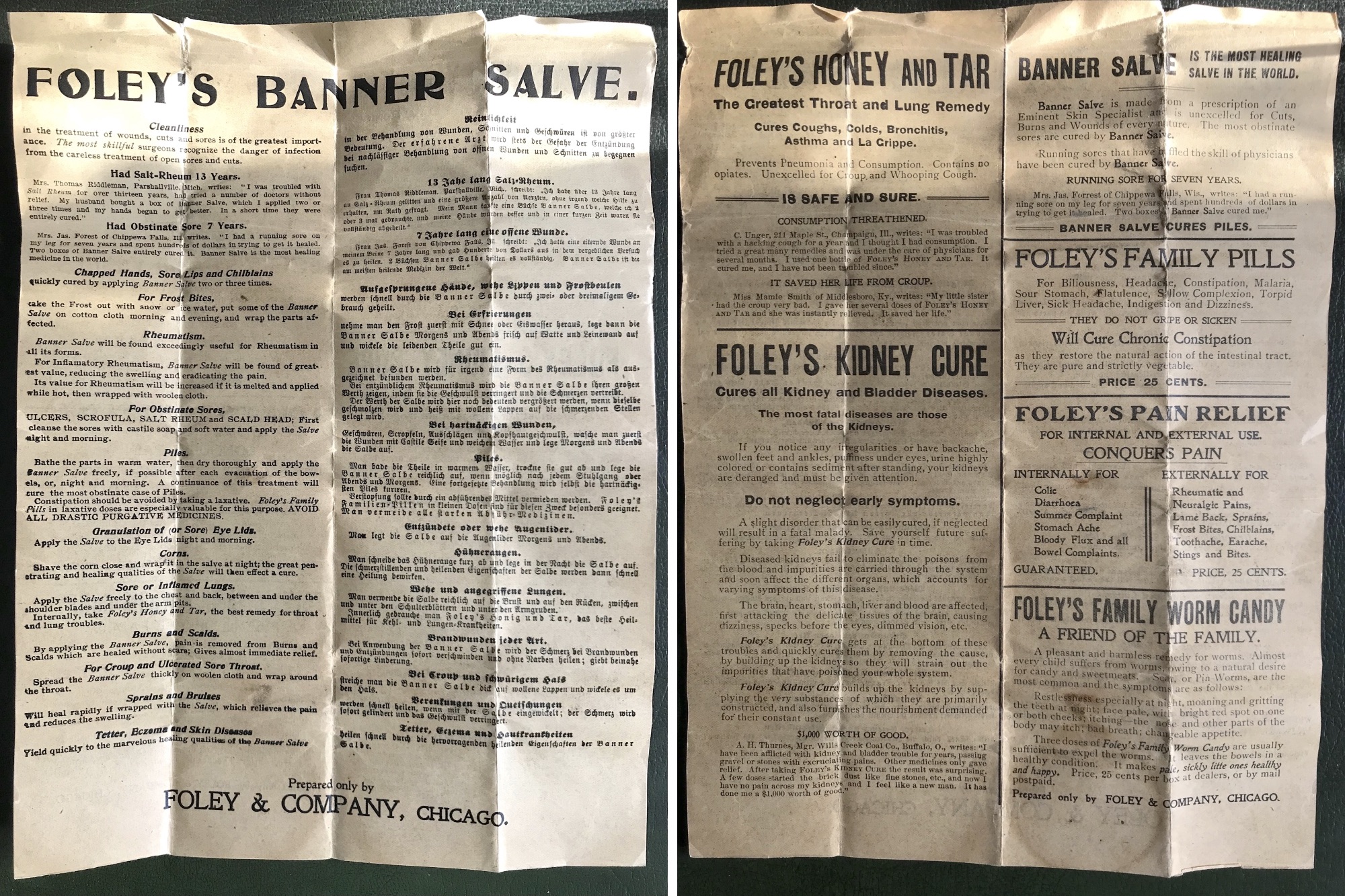

The “Banner Salve” in our museum collection likely dates from the first decade of the 1900s, when it was widely promoted in papers nationwide as “the most healing salve in the world.”

“Banner Salve is made from a prescription of an Eminent Skin Specialist,” claims the advertising sheet folded inside the packaging, “and is unexcelled for Cuts, Burns and Wounds of every nature. . . Running sores that have baffled the skill of physicians have been cured by Banner Salve.”

Like all Foley medicines of this era, advertisements for Banner Salve provided very little info on its chemical composition or ingredients, focusing more on bold testimonials from random satisfied customers.

“I had a running sore on my left leg for seven years,” a Mrs. Jas. Forrest of Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin, supposedly wrote to Foley & Co. “I spent hundreds of dollars in trying to get it healed. Two boxes of Banner Salve cured me!”

Of course, we can’t disprove Mrs. Forrest’s experience any more than we can say, for certain, whether John Foley was an upstanding businessman or a snake oil salesman. In the eyes of some men, the two need not have been mutually exclusive.

History of Foley & Co., Part I: The Ohio Druggist

Though he was born in Chicago in 1857, John B. Foley grew up in Steubenville, Ohio, where his family moved when he was still a toddler. Foley’s Irish-born father worked in the paper mills in Steubenville, and his mother cared for the eight kids in the house, of which John was the second oldest.

In his teens, Foley got a job in a local drug store, where he learned as much about salesmanship, slogans, and marketing as he did about actual pharmaceutical remedies. He attended public high school and never went on to college, but we can infer from his later published writings as a member of Chicago’s exclusive Marquette Club (a sort of rich young Republicans society) that he was highly motivated intellectually, with ambition to boot. By 21, he was a bookkeeper for one of the paper mills in town, and by 24, he’d squirreled away enough scratch to buy out the wholesale business of Steubenville druggist W. D. MacGregor.

In his teens, Foley got a job in a local drug store, where he learned as much about salesmanship, slogans, and marketing as he did about actual pharmaceutical remedies. He attended public high school and never went on to college, but we can infer from his later published writings as a member of Chicago’s exclusive Marquette Club (a sort of rich young Republicans society) that he was highly motivated intellectually, with ambition to boot. By 21, he was a bookkeeper for one of the paper mills in town, and by 24, he’d squirreled away enough scratch to buy out the wholesale business of Steubenville druggist W. D. MacGregor.

It’s possible that Foley started making his own medicines for altruistic reasons, but it’s also likely he was well aware—from his experience as a pharmacy clerk—that there was big money to be made in this unregulated industry. According to the Chicago Tribune, it was around 1885 that he entered into “the manufacture, on a small scale, of proprietary medicines and toilet preparations. . . . He moved to Chicago in 1888 and began manufacturing on a larger scale.” [Interestingly, later Foley ads of the 20th century often identify the company’s date of establishment as 1875, suggesting they counted John Foley’s days as a teenage druggist as the true ‘beginning’ of his enterprise].

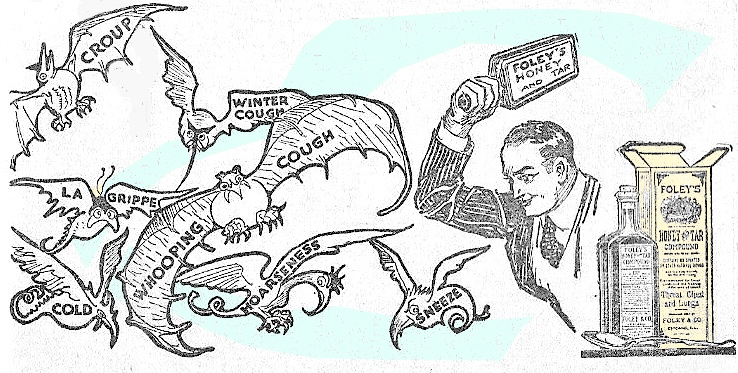

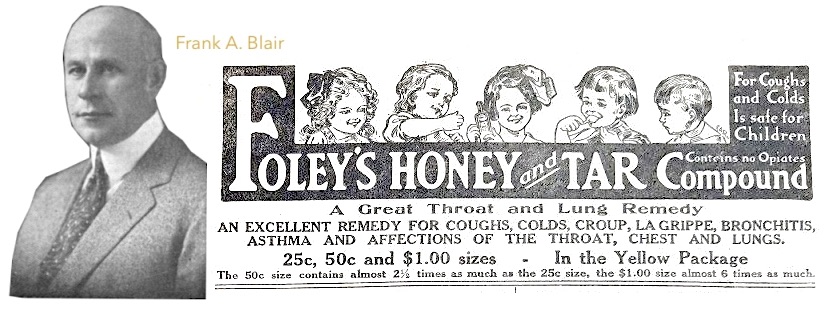

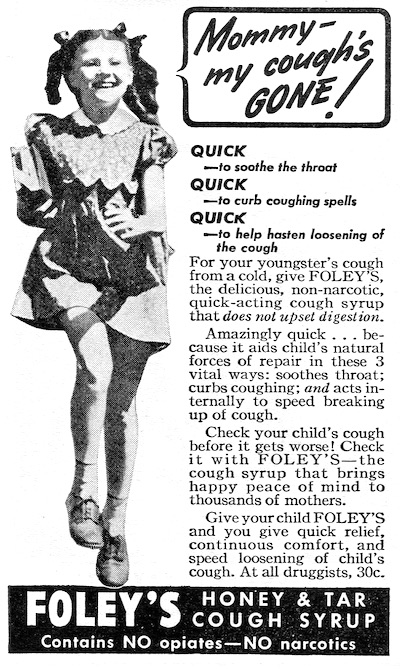

Within months of his arrival on the shores of Lake Michigan, Foley hired a sales team to start chatting up druggists far and wide about his new line of original “cures,” highlighted by Foley’s Honey & Tar Cough Syrup: “the best cure for coughs, colds and all lung troubles,” according to an 1889 ad in a Pennsylvania paper. It would later be promoted as the “largest selling cough medicine in the world.”

[Advertisements for Foley’s Honey & Tar Cough Syrup, 1903]

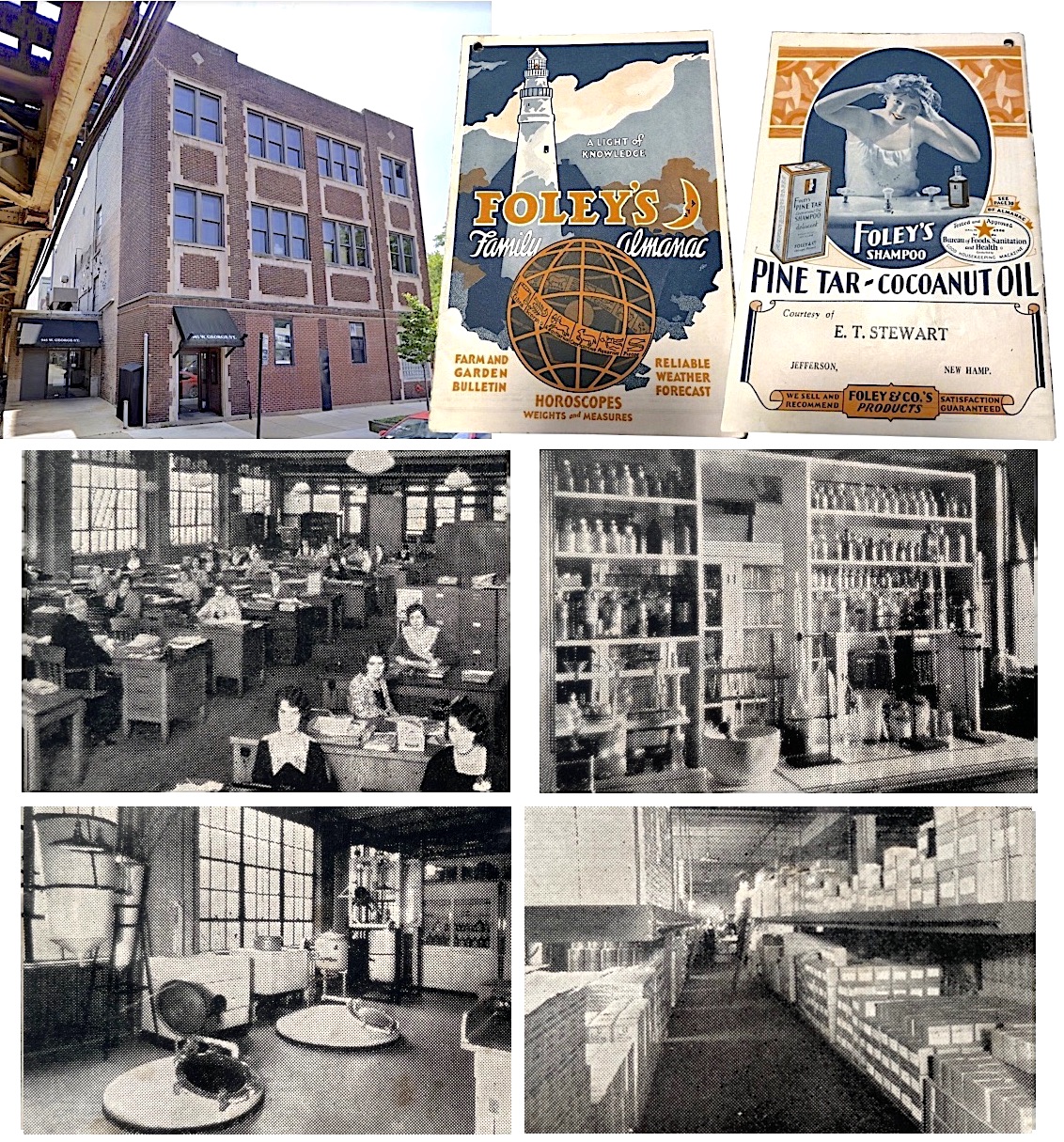

With their distribution network growing, Foley & Co. expanded its humble manufacturing operations, occupying a headquarters at the corner of Ohio Street and Orleans Street (a spot then known as 92-96 E. Ohio Street under the old Chicago street numbering system) and employing a staff of 17 workers by 1896.

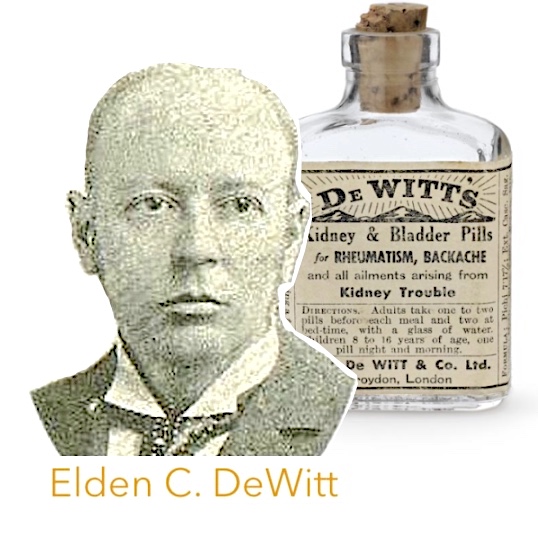

It was not in John Foley’s nature to be satisfied with these developments. Still a year shy of his 40th birthday, he’d already managed to elbow his way into some of Chicago’s elite business circles, winning over the city’s snobbiest industrialists with his brash opinions on capitalist Republican ideals and Grover Cleveland’s foreign policy failures. As director and chairman of the Marquette Club’s membership committee, Foley also regularly rubbed shoulders with the president of that organization, E. C. DeWitt—a young, like-minded patent medicine peddler whose factory already employed 4-times the workforce of Foley & Co.

“DeWitt ain’t got nothing on me,” Foley might have murmured to himself, enviously twirling his mustache. It’s also possible that DeWitt was more of a friend and mentor, coaching the Ohio kid in the Chicago method of industrial-scale quackamatics. Either way, Foley was inspired, and he redoubled his efforts into the new century.

“DeWitt ain’t got nothing on me,” Foley might have murmured to himself, enviously twirling his mustache. It’s also possible that DeWitt was more of a friend and mentor, coaching the Ohio kid in the Chicago method of industrial-scale quackamatics. Either way, Foley was inspired, and he redoubled his efforts into the new century.

Foley & Co. grew to a staff of 47 employees by 1900, and after an expansion of the factory and offices on Ohio Street, the team was up to 110 workers (84 women and 26 men) by 1905. Some were there to mix up the medicines in the lab, while probably quite a few more were needed for the laborious packaging and shipping operations, making sure each little yellow box was properly filled and ready to work its magic.

[Top Left: Building 319-333 W. Ohio Street, formerly known as 92-96 E. Ohio Street, where Foley & Co. occupied at least two floors during the 1900s. Right: A countertop ad for Foley’s Family Favorite Worm Candy (which was intended not as a dessert, but to treat children suffering from worms). Bottom: 1908 ad seeking girls to work in the Foley lab. Lower Left: Our museum’s tin of Banner Salve, circa 1900s.]

II. “Healthfulness of Climate”

After nearly 20 years in the trade and with his fortune more than solidified, John Foley had the freedom for more flights of fancy in the early 1900s, including fostering his own little utopia in Baldwin County, Alabama, and starting a second business—the Magnolia Springs Land Company—as a way to recruit other Chicagoans to join him in the effort.

“For healthfulness of climate, productiveness of soil, and pleasant surroundings, our land in southern Baldwin County, Alabama, is the best in the world,” read a 1903 Magnolia Springs advertisement posted in the Chicago Tribune. “A few hundred dollars will make you independent. Send for illustrated booklet.”

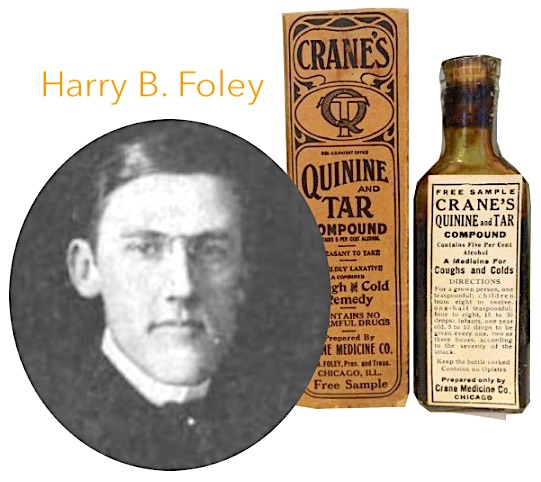

With Foley distracted by his namesake town, more of the responsibility of running the Chicago drug empire was put in the hands of his younger business partners, including general manager Frank A. Blair (b. 1870) and Foley’s own brother and company vice president Harry B. Foley (b. 1874), who was 17 years his junior.

A boisterous, well-spoken chap much like his big bro, Harry became something of a warrior for the entire patent medicine industry, as he and Blair both took on leadership roles with the Proprietary Association of America. This organization was mainly tasked with defending patent drug makers against their many critics and foes, including the U.S. government—which had brought in sweeping regulations with the Pure Food & Drug Act of 1906—as well as local druggists across the country, who were undermining manufacturers by selling their own homemade versions of popular boxed drugs.

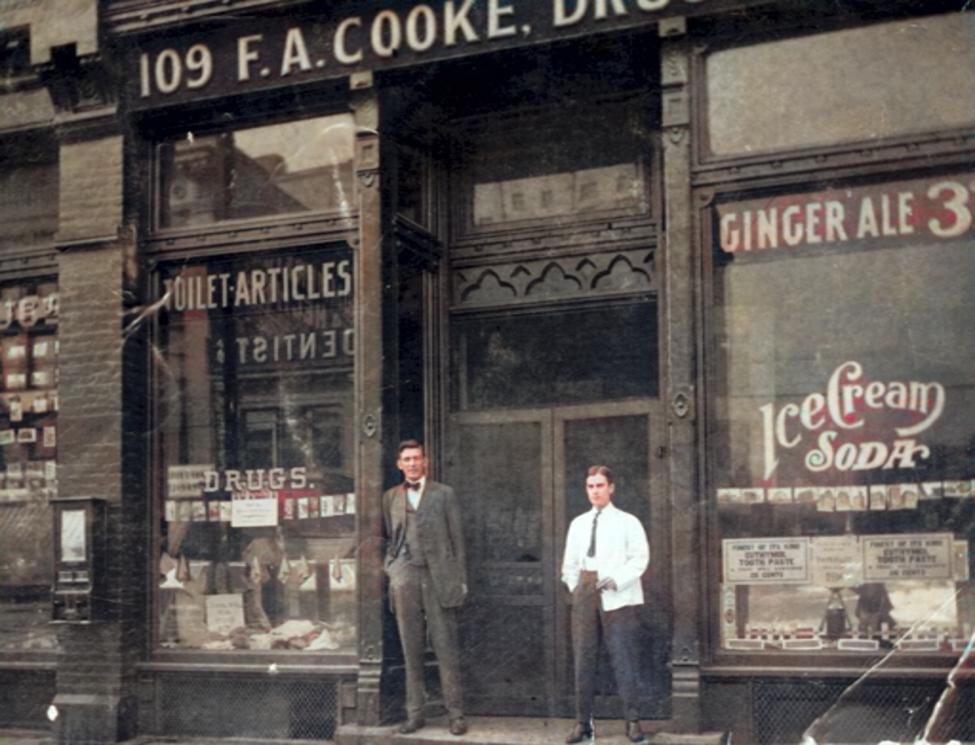

“There seems to be a disposition in some quarters to urge druggists to push non-secrets and their ‘own make’ preparations instead of furthering the sale of advertised proprietary medicines,” an agitated Harry Foley wrote in a 1907 issue of the Western Druggist, noting that at least 50% of the total business done by drug stores depended on companies like Foley & Co. “They seem to lose sight of the fact that selling proprietary medicines requires no special skill, and from the money making standpoint they should congratulate themselves that they are the distributing agents of the manufacturers instead of deploring the fact.”

[An early 1900s Chicago drug store]

Of course, while Harry felt there was no skill needed to sell a patent drug, a lot of druggists had clearly decided that no particular talent was needed to manufacture one, either. And it was hard to disprove the point. Even the term “patent medicine” was already well outdated, since most 20th century manufacturers could no longer meet the basic requirements to earn a U.S. patent in the first place.

We don’t know if Harry Foley and John Foley were in lockstep when it came to these various commercial battles, but by 1909, something had clearly created a wedge between the brothers themselves. Harry left the company that year and promptly joined a Chicago competitor, the Crane Medicine Co. In turn, Foley & Co. filed an injunction against Harry and his new employer, restraining them from selling any products that imitated Foley drugs in name or appearance. “Foley and Company will of course prosecute any attempt at imitation of the names or packages of their products,” the company announced in a 1911 newspaper ad. “The original and genuine Foley’s Honey and Tar and Foley’s Kidney Pills, which do not and never have contained any opiates or habit-forming drugs, and are put up in a yellow package, are being supplied as formerly.”

We don’t know if Harry Foley and John Foley were in lockstep when it came to these various commercial battles, but by 1909, something had clearly created a wedge between the brothers themselves. Harry left the company that year and promptly joined a Chicago competitor, the Crane Medicine Co. In turn, Foley & Co. filed an injunction against Harry and his new employer, restraining them from selling any products that imitated Foley drugs in name or appearance. “Foley and Company will of course prosecute any attempt at imitation of the names or packages of their products,” the company announced in a 1911 newspaper ad. “The original and genuine Foley’s Honey and Tar and Foley’s Kidney Pills, which do not and never have contained any opiates or habit-forming drugs, and are put up in a yellow package, are being supplied as formerly.”

With Harry Foley out of the picture, Frank A. Blair really became the face of Foley & Company in the 1910s. He was also elected president of the Proprietary Association of America during some of its most combative years before and after World War I—a time when Foley’s Honey & Tar was briefly promoted as a preventative for the Spanish Flu.

Blair, who’d been a traveling shoe salesman before joining Foley & Co. back in 1896, had zero background in medicine, but all the confidence one could ask for from a pharmaceutical spokesman.

“Not only does the broad industry of the United States depend on the proprietary business for a worthwhile part of its income,” Blair told the publication Standard Remedies in 1920, “but the people themselves demand its products. They need them; otherwise they would not have paid $380 million at retail for them last year.”

Incidentally, $380 million in 1920 is equivalent to nearly $5 billion in today’s marketplace; a clear indication of just how strong the quack drug business still was in the “modern era.”

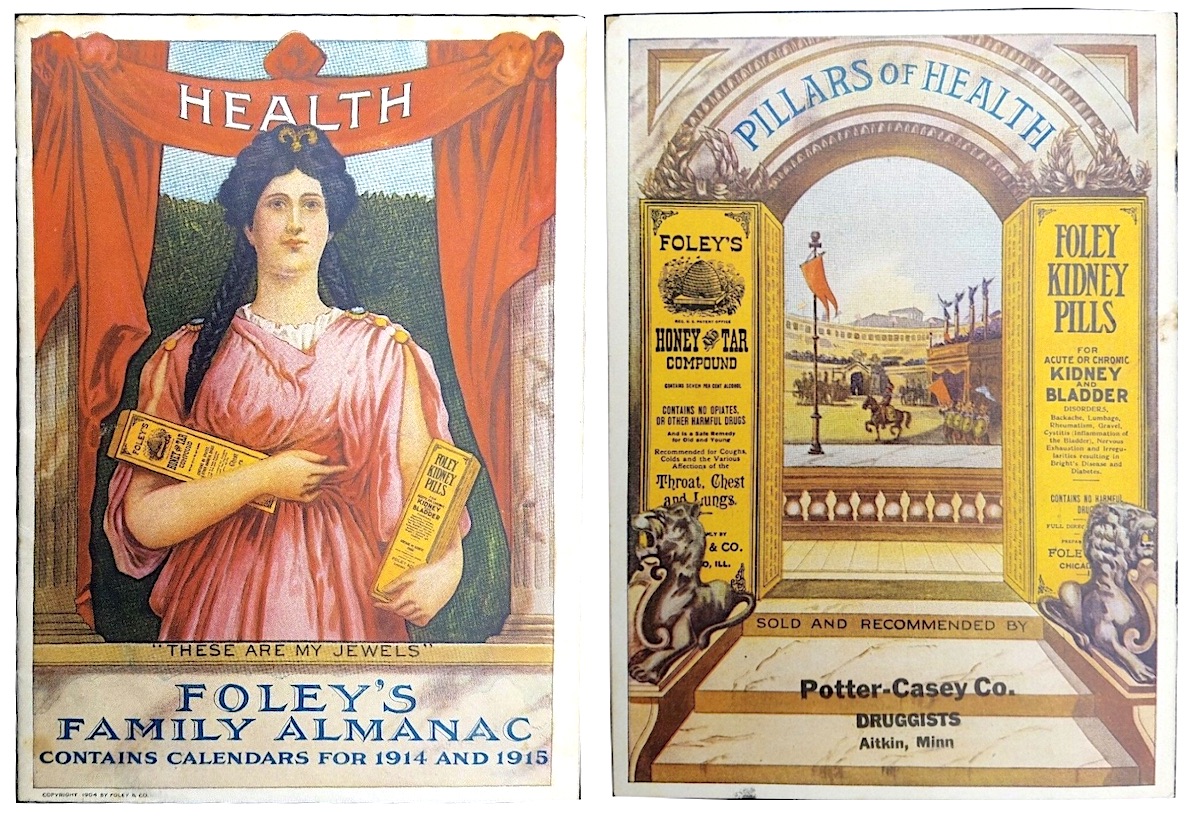

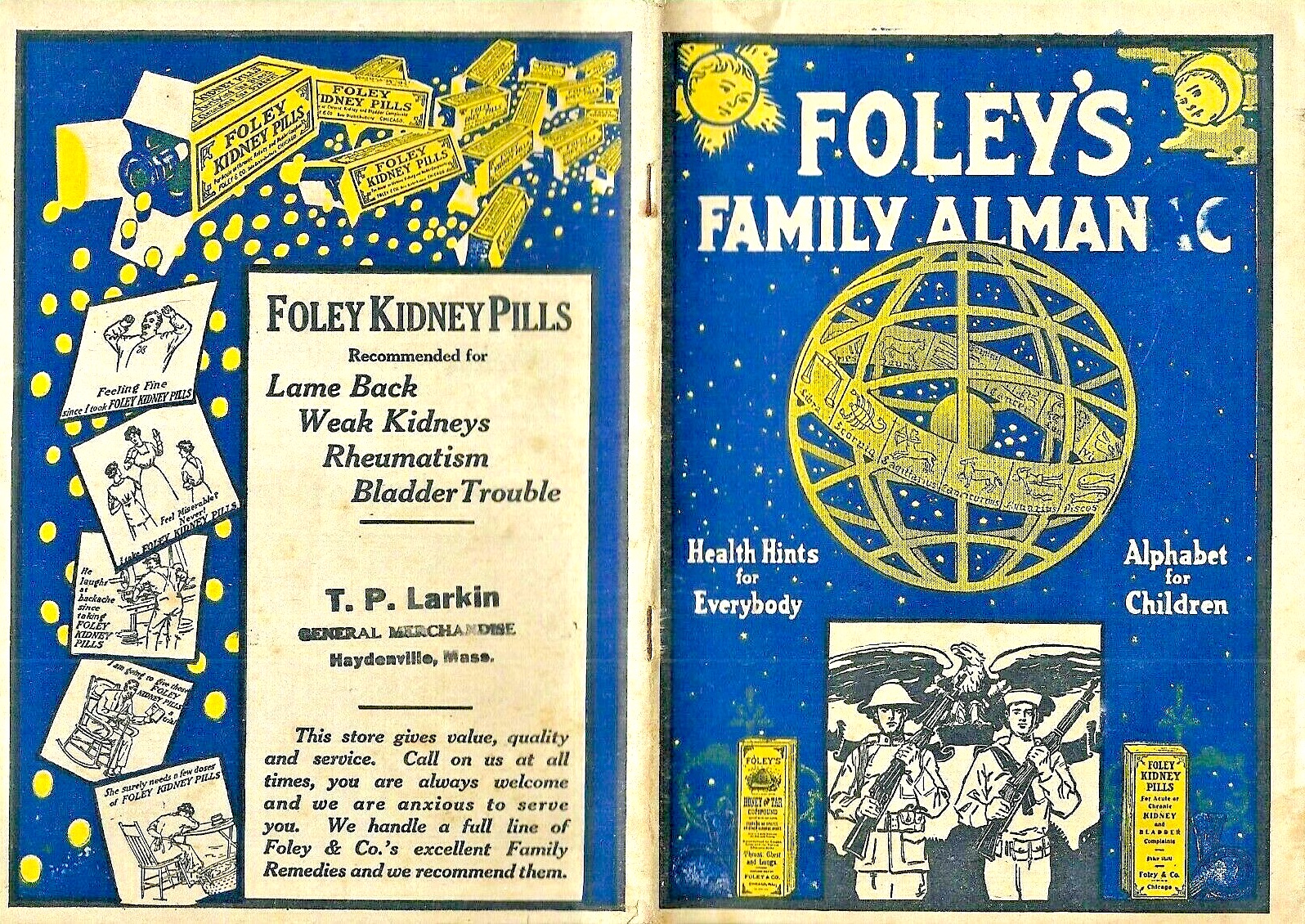

[Above: Foley & Co. employees at the annual company picnic and field day in 1920 (photo provided by Ken Wodrich, whose grandfather is in the photo). Below: Front and back of Foley’s Family Almanac, 1914 edition]

III. All That’s Fit, and Unfit, to Print

“We are glad to present to you this copy of FOLEY’S FAMILY ALMANAC. . . . If we have succeeded in telling you herein anything that will help you with the aid of FOLEY & CO’s MEDICINES, to ward off sickness, to cure diseases, to regain health and strength, then we have done a GOOD WORK.” —intro to the 1914 edition of Foley’s Family Almanac

At its peak, Foley & Company was very nearly a printing business first; a drug business second—that’s how much self promotion meant to the success of the operation.

In 1912, when he moved the factory and offices to a new five-story building at the corner of North Sheffield Avenue and West Wolfram Street, John Foley made sure the complex included a dedicated printing department for producing the company’s annual “Family Almanac” and other advertising paraphernalia. Again, this was following the E.C. DeWitt marketing playbook, and as no coincidence, E.C. DeWitt & Co. would eventually buy out the Sheffield Avenue building for its own use after John Foley’s death. During the 1910s and ‘20s, though, Foley’s printing business was wildly prolific—as evidenced by the wide assortment of their old booklets and flyers that remain easy to find in eBay stores or your grandparents’ attic.

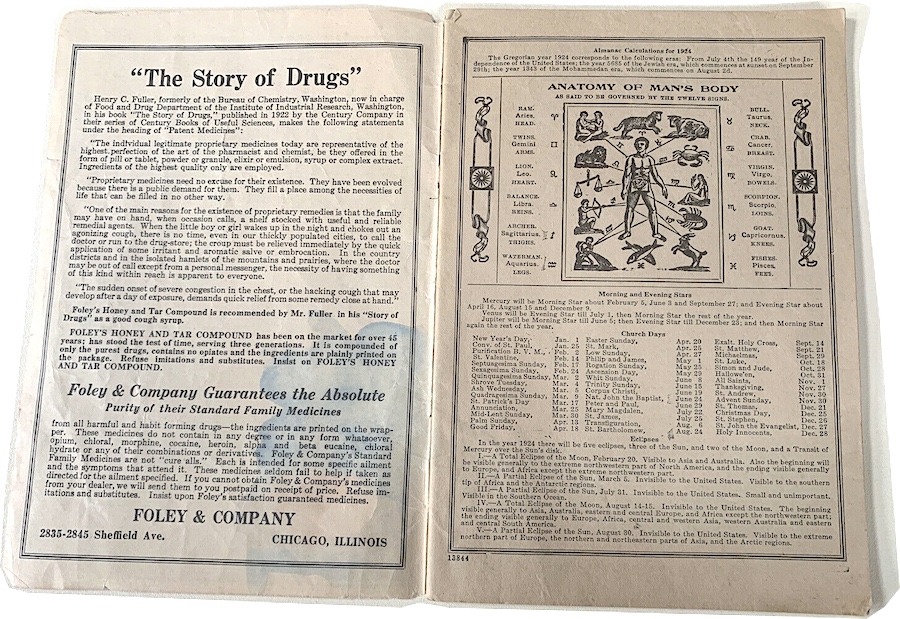

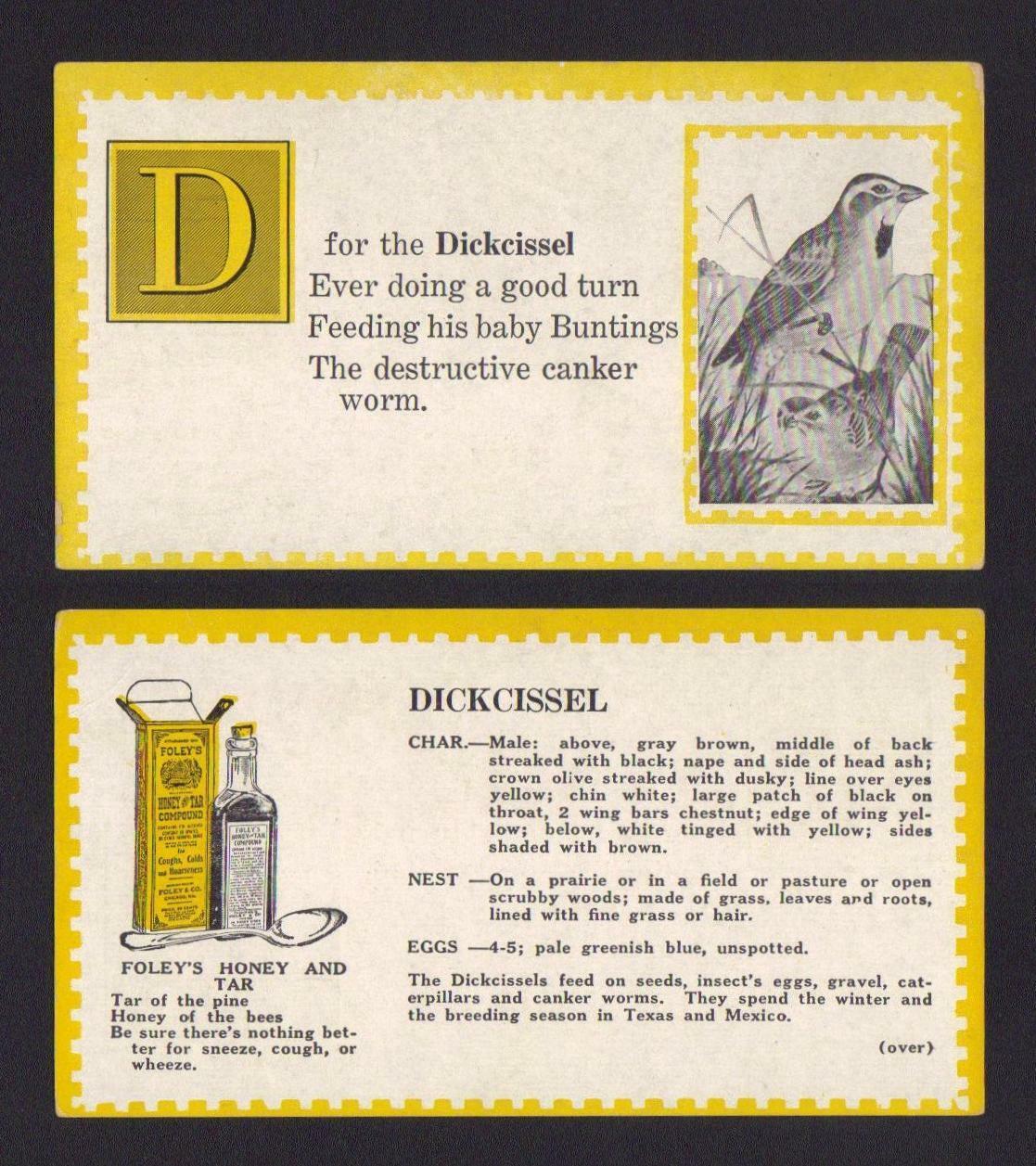

The colorful “Foley Family Almanac and Health Book,” much like similar booklets sold by DeWitt and other patent drug companies, included horoscopes, weather predictions, and random amusements such as “Bird Alphabet Cut-Out Cards.” This was all just window dressing, of course, as 90% of each issue was filled with ads for Foley’s endless arsenal of medicines: Honey & Tar, Foley’s Cathartic Tablets, Foley’s Orino Laxative, Foley’s Foot & Corn Relief, Foley’s Kidney Pills, Foley’s Banner Salve, etc. etc.

[Foley’s Family Almanac, 1918]

The self-serving intent of each almanac was always the same, although there was a slight evolution in the tone and messaging from year to year, as increasing government regulations and general public speculation around the legitimacy and safety of patent medicines led to increasingly defensive language from the Foley camp.

“Foley & Company guarantees the absolute purity of their standard family medicines from all harmful and habit forming drugs—the ingredients are printed on the wrapper,” read the intro to the 1924 almanac, which also included a fairly new confession that Foley products “are NOT cure-alls. Each is intended for some specific ailment and the symptoms that attend it.”

The company was using the right legal-ease, but it was usually a case of doing the bare minimum to keep the feds off their back. In fact, while the “cure” word was largely banished, that same 1924 catalog introduced a different technique to ease consumer concerns—prominently quoting a controversial new book called “The Story of Drugs,” in which author Henry C. Fuller (essentially a stooge employed by Frank Blair) claimed that “Proprietary medicines today are representative of the highest perfection of the art of the pharmacist and chemist, be they offered in the form of a pill or tablet, powder or granule, elixir or emulsion, syrup or complex extract. . . . They fill a place among the necessities of life that can be filled in no other way.”

The company was using the right legal-ease, but it was usually a case of doing the bare minimum to keep the feds off their back. In fact, while the “cure” word was largely banished, that same 1924 catalog introduced a different technique to ease consumer concerns—prominently quoting a controversial new book called “The Story of Drugs,” in which author Henry C. Fuller (essentially a stooge employed by Frank Blair) claimed that “Proprietary medicines today are representative of the highest perfection of the art of the pharmacist and chemist, be they offered in the form of a pill or tablet, powder or granule, elixir or emulsion, syrup or complex extract. . . . They fill a place among the necessities of life that can be filled in no other way.”

Unsurprisingly, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) took a slightly different view, calling Fuller’s book a “whitewashing” of the patent medicine business. “It is clear that Mr. Fuller has done the ‘patent medicine’ industry a distinct service,” the Journal lamented. “What he has done for the public is not so clear.”

In another edition of the JAMA, published in 1924, a recent court case is detailed, in which federal authorities found Foley & Co. guilty of using “false and fraudulent claims” in promoting Foley’s Kidney Pills. “These pills were analyzed by the chemists of the Bureau of Chemistry, who reported that they contained potassium nitrate, methylene blue, hexamethylenetetramine, and plant material, including resin and juniper oil. These pills, although they contained kidney irritants, were recommended to people suffering from disease of the kidneys.”

Legal cases regarding “misbranded nostrums” were so common in the 1920s that few of them ever elevated to the level of a national scandal. The Foley Kidney Pill case certainly made news in Foley, Alabama, however, where a newspaper called the Onlooker printed the American Medical Association report and criticized another local paper, the Baldwin County News, for refusing to hold the wealthy town founder John Foley to account for his apparent misdeeds.

“The [Baldwin County] News would not print anything that did not satisfy their millionaire friend,” the scathing Onlooker story claimed, “even though it be of interest and VALUE to their readers. What if people did take kidney pills containing only irritants to the kidneys? It is perfectly alright so long as the money goes to John Burton Foley and from him to his various pet fancies. Yea, brother, money talks, but sometimes it talks too confounded loud.”

“The [Baldwin County] News would not print anything that did not satisfy their millionaire friend,” the scathing Onlooker story claimed, “even though it be of interest and VALUE to their readers. What if people did take kidney pills containing only irritants to the kidneys? It is perfectly alright so long as the money goes to John Burton Foley and from him to his various pet fancies. Yea, brother, money talks, but sometimes it talks too confounded loud.”

Interestingly, the Onlooker never seemed to take such a critical eye to Foley again, and after his death in 1925, the same newspaper referred to him as “an empire builder . . . known not only for his successful business career, but for his genuine whole-souled charity and love for his fellow men. When the Guardian Angel opens his Book of Life, he will read the name of John Burton Foley with the record of his many kind deeds. . . . South Baldwin’s prosperous farms, and the broad avenues of the town of Foley, lined, as they are today, with substantial business blocks such as are rare in towns of like size, are a lasting tribute to his sagacity and constructive dreaming.”

[Foley’s list of “Reliable Family Remedies” in the 1920s included old standards like Foley’s Pain Relief, as well as new bathroom products like “Oriole Talc,” sold in a very handsome tin]

IV. Used as Directed

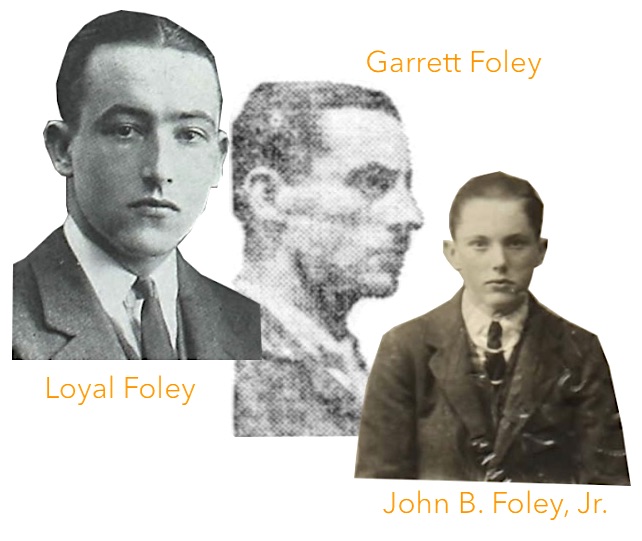

John Foley’s death was unexpected. On February 4, 1925, he attended a performance of “The Rivals” (starring the celebrated actress Minnie Maddern Fiske as Mrs. Malaprop) at Chicago’s Illinois Theater, accompanied by his wife Anna. During the show, he suffered a stroke and never woke up. By this point, the couple’s five children were all grown up, and it fell upon the three sons, Garrett (b. 1896), Loyal (b. 1898), and John Jr. (b. 1905), to plot the course of the family businesses.

Garrett Foley, who had a Harvard degree and took a bullet in France during World War I, was given the reins of the Magnolia Springs Land Company; in that capacity, he moved from Chicago to Foley, Alabama, in 1928, and spent most of the rest of his life there.

Loyal Ludington Foley, also a Harvard man, was named president of Foley & Company in Chicago (Frank Blair had since left for another firm). After two years on the job, he decided to shut down the printing business and consolidate a bit, selling off the Sheffield Avenue building to E.C. DeWitt & Co, and establishing a new, smaller headquarters at 945-947 W. George Street—about 270 feet from the previous spot. According to his ex-wife Carlisle Sullivan, Loyal was ironically not so loyal of a husband, as their divorce was granted in 1932 based on grounds of desertion—Loyal had been living in the Drake Hotel for two years in a sort of married bachelordom.

Loyal Foley didn’t necessarily usher in a new ethical standard for Foley & Co., either. During the Depression and World War II, despite expanding into more relatively harmless bathroom and cosmetic products, the company was still routinely hounded by the Federal Trade Commission for using misleading statements in its advertising. The resulting stress of slowing sales and court cases might have gotten to the Foley sons a bit.

[Foley & Co. moved to the Lake View building above at 945-947 W. George Street in 1927, and remained there until leaving the city in 1957. Also pictured is the company’s 1932 Almanac and interior shots of the George Street plant that year, including the General Offices (top left), Compounding Room (bottom left), Testing Laboratory (top right), and Shipping Room (bottom right)]

In 1940, Loyal Foley died of unknown causes at just 42 years of age. Eldest brother Garrett fell to a heart attack eight years later at age 51, leaving the slumping business in the hands of 43 year-old John Burton Foley, Jr.

As much as John Jr. might have wanted to right the ship, it was hard to fully bring a 19th century patent medicine business into the good graces of American regulators in the Space Age. As late as 1952, Foley’s oldest flagship product, Honey & Tar Cough Syrup, was the target of a major FTC crackdown. For nearly 70 years, first in newspapers and later in radio, the company had touted Honey & Tar’s ability to deliver “speedy relief and a quicker recovery” from the common cold. Unfortunately, under closer examination in government labs, the mixture of terpin, pine tar, honey, brown sugar, and gum arabic wasn’t really found to have much significant therapeutic value at all, leading to a cease-and-desist order on all such future advertising.

“Foley & Company’s use of false and misleading statements and representations,” the FTC report determined, “has had the tendency and capacity to mislead and deceive a substantial portion of the purchasing public.”

Business continued in the same George Street office building until 1957, when John Foley Jr. opted to bring the two halves of his father’s legacy together, moving Foley & Co. to Foley, Alabama. There, a new 12,000 square foot HQ opened with just 12 workers on staff. Overall, this new era was brief.

In 1963, a Pennsylvania based company called Myers Laboratories Inc. bought out Foley & Co. and all its assets, moving them to Warren, PA. Gordon Hanks, president of Myers at the time, singled out Foley’s Honey & Tar Cough Syrup as “the most famous” of the 12 proprietary drug items his firm had just acquired. And yet, from the looks of it, this basically marked the end of the Foley name as a relevant trademark in the pharmacy biz.

Sources

Foley’s Family Almanac – 1914, 1918, 1924, and 1932 editions

“Foley & Co., Chicago, IL” – Old Main Artifacts

“Proprietary Business Vital to Nation, Says Frank A. Blair” – Standard Remedies, April 1920

“In the Matter of Foley & Co., et al” – Federal Trade Commission Decisions, Jan 16, 1952

“An Apologist for Patent Medicines” – Journal of the American Medical Assoc., May 13, 1923

“More Misbranded Nostrums – Foley’s Kidney Pills” – Journal of the American Medical Assoc., July 12, 1924

“President of the Proprietary Association” – The N.A.R.D. Journal, April 3, 1924

“All Agree with Monroe: Marquette Members Fully Indorse the Famous Doctrine” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 29, 1895

“For the City’s Good: Magnificent Work Accomplished By the Marquette Club” – The Inter Ocean, Jan 1, 1896

“The Druggist and Proprietary Medicines,” by Harry B. Foley, The Western Druggist, April 1907

“Bullet Just Misses Heart of Chicago Boy: Garrett R. Foley Shot First Day in the Trenches” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 30, 1917

“John B. Foley, Financier, Drops Dead in Theater” – Chicago Tribune, Feb 5, 1925

“John Burton Foley Dies” – Cincinnati Enquirer, Feb 5, 1925

“J. B. Foley Victim of Stroke While Attending Show” – The Onlooker (Foley, AL), Feb 12, 1925

“Source of Satisfaction” – The Onlooker (Foley, AL), Aug 21, 1924

“DeWitt & Co. Buy Factory Building from Foley & Co.” – Chicago Tribune, Aug 7, 1927

“John Burton Foley: Chicago Capitalist, Founder of Foley, AL” – The Onlooker (Foley, AL), Feb 16, 1928

“Gets Divorce (Carlisle Sullivan Foley)” – Chicago Tribune, May 6, 1932

“Cough Syrup: Qualities, Properties or Results” – Federal Trade Commission Decisions, Dec 18, 1940

Loyal L. Foley obit – Chicago Tribune, Nov 24, 1940

“Foley Citizen Dies Tuesday Unexpectedly” (Garrett Foley obit) – The Onlooker (Foley, AL), May 13, 1948

“Work Is Started On New Building for Foley Firm” – Pensacola News Journal, March 10, 1957

“Myers Laboratories Adds Four More Drug Firms” – Warren Times Mirror (Warren, PA), May 6, 1963

It’s hard to find those ABC Bird Cards! I have one set (@5″ x 2.75″) missing the Q (Quail) card, and I have another set, same birds but smaller (@ 3.5″ x 2″) missing the H (Hummingbird) Card. If anyone has an incomplete set that happens to include one of these, and would be willing to sell it/them, please let me know. Thanks! Brooke Neer, Richmond, VA

I have an in opened bottle of Foley kidney pills with the New added feature kidney-stimulating diuretic. Just curious if this is a rare bottle?

Hi

I have a PHOTO of Foley & Co. picnic August 7th 1920.

My grandfather is in the picture.

I still have the wool jersey from the baseball team the company sponsored.

Would you like for your historic picture?

My Father worked for Eastern Airlines. They had small bags often handed out to passengers. Most has needle and tread, and small tube of Foleys Salve. I can remember the fragrance to this day. It was good product for a skinned knee or minor cut.

My grandfather’s best known product was Foley & Company’s “Honey and Tar” Cough Syrup, named for a couple of mules my dad said. John Foley

Hey there Andrew. Foley and co was a patent medicine company based out of Chicago in the early 20th century (I think founded in the late 19th century?). The founders were Henry and John Foley. John Foley founded Foley Alabama. I understand that’s where he invested a lot of his own money from Foley and co including a hotel (magnolia hotel) and railroad down there. I don’t have much info on Henry Foley other than he left Foley and co to work for Crane Medicine Company in 1909. John Foley is my great – great grandfather. I wish I had more personal artifacts or stories but I’ve just been learning about everything from scratch!

I found a small clear cork type bottle with Filey & Co on the side. Maybe a 1/2oz bottle. Would that be Honey and Tar bottle?