Museum Artifacts: Franklin D. Roosevelt Pinback Campaign Button (1936), and 22 Pinbacks of Flags from Around the World (c. 1920s)

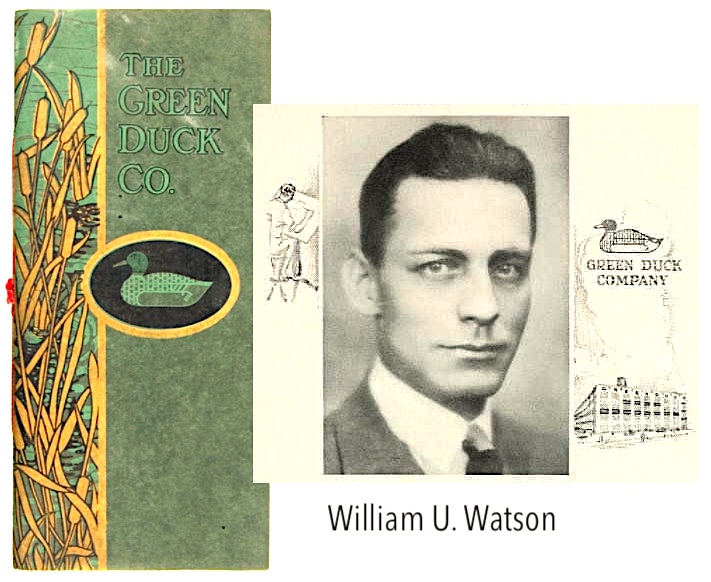

Made By: The Green Duck Company, 1725 W. North Ave., Chicago, IL [Wicker Park]

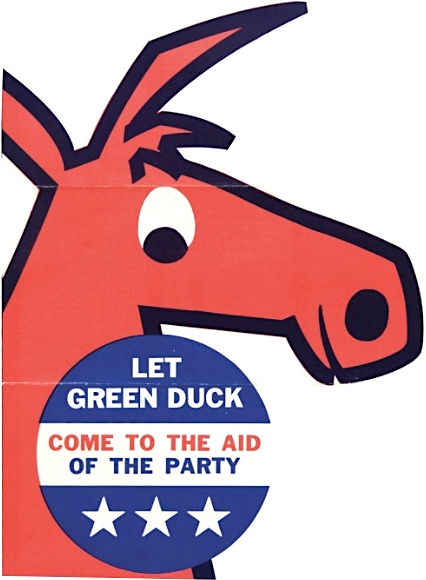

“We were as happy to be of service to the GOP as to the Democrats, and vice versa. Where politics is concerned, ‘I’m For Me’ and Green Duck is for Green Duck. That’s the way it’s got to be.” —Green Duck Company vice president Earl Butler, 1960

For six decades, Chicago’s oddly named Green Duck Company was one of the country’s leading manufacturers of campaign buttons, along with many other small metal advertising novelties. In a city almost proudly notorious for its political corruption, this unshakeable firm was refreshingly cavalier in its non-allegiance to any particular party, candidate, or cause. Instead, they happily stamped out paraphernalia for anybody willing to pay the going rate for it—be it the local game warden or the President of the United States.

For six decades, Chicago’s oddly named Green Duck Company was one of the country’s leading manufacturers of campaign buttons, along with many other small metal advertising novelties. In a city almost proudly notorious for its political corruption, this unshakeable firm was refreshingly cavalier in its non-allegiance to any particular party, candidate, or cause. Instead, they happily stamped out paraphernalia for anybody willing to pay the going rate for it—be it the local game warden or the President of the United States.

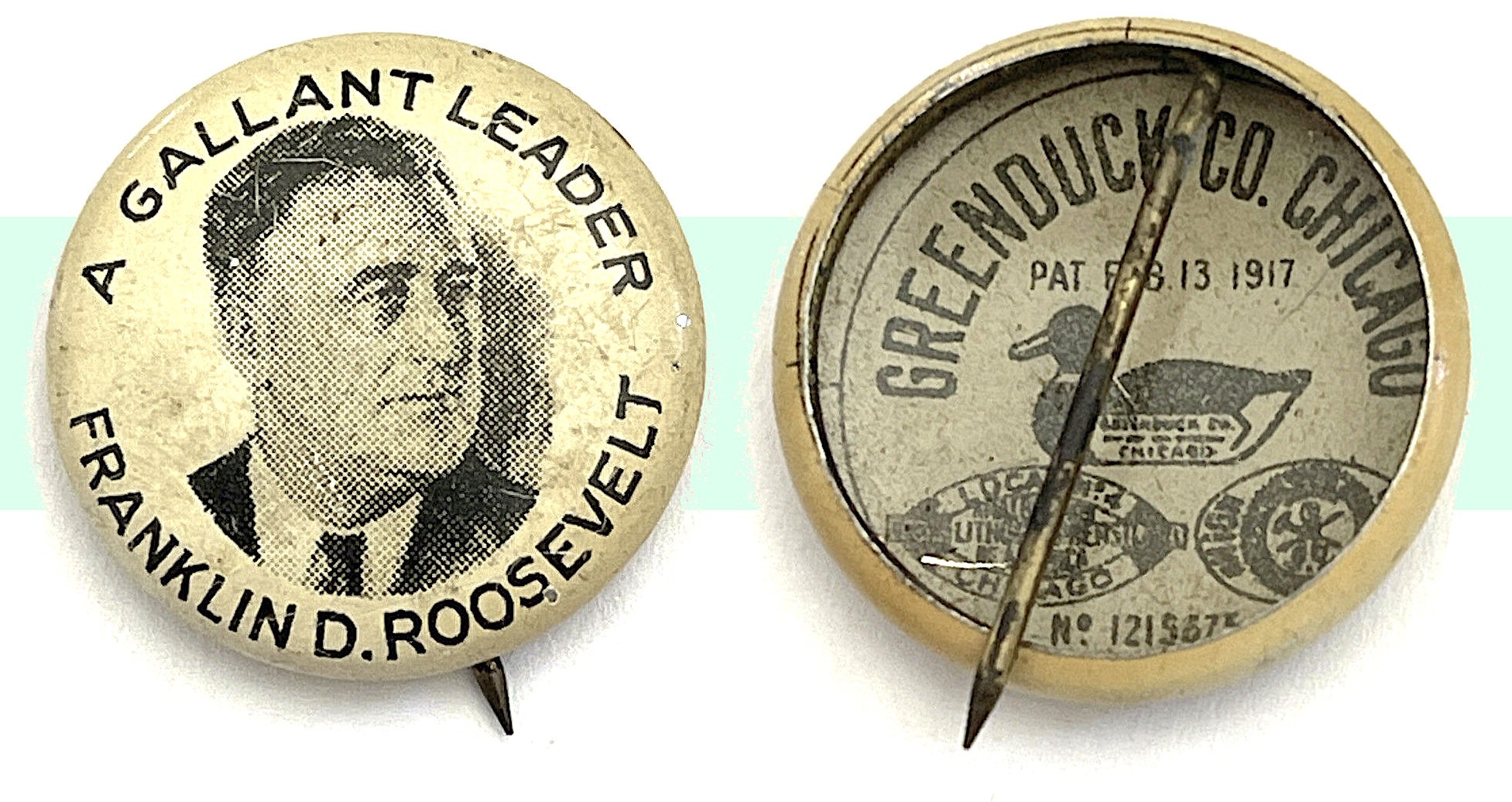

In 1936, for example, Green Duck produced many thousands of the penny-sized pinback featured in our museum collection, calling for the re-election of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a “Gallant Leader.” True to form, however, the company was also a key cog—just four years later— in the anti-Roosevelt merchandising machine of FDR’s 1940 presidential opponent, Wendell Willkie. That year, by early October, Green Duck’s Wicker Park plant had shipped out 20 million Willkie buttons compared to roughly 8 million for the incumbent, with many of the most popular sellers using slogans like: “Roosevelt for Ex-President,” “No Roosevelt Dynasty,” “No Third Termites,” and of course, “We Don’t Want Eleanor, Either.”

Unlike many of their clients, Green Duck was never directly linked to organized crime, but their self-serving modus operandi and political sway bared at least a little resemblance. Unfortunately, when profits took a turn for the worse, the company’s founder also met a tragic and violent end worthy of a gangster story.

History of the Green Duck Company, Part I: Greenburg & Duckgeischel

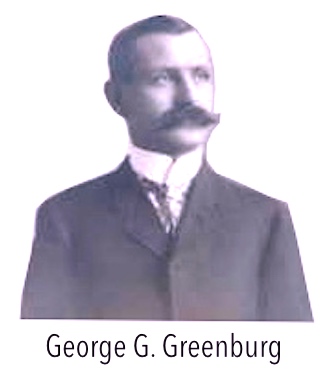

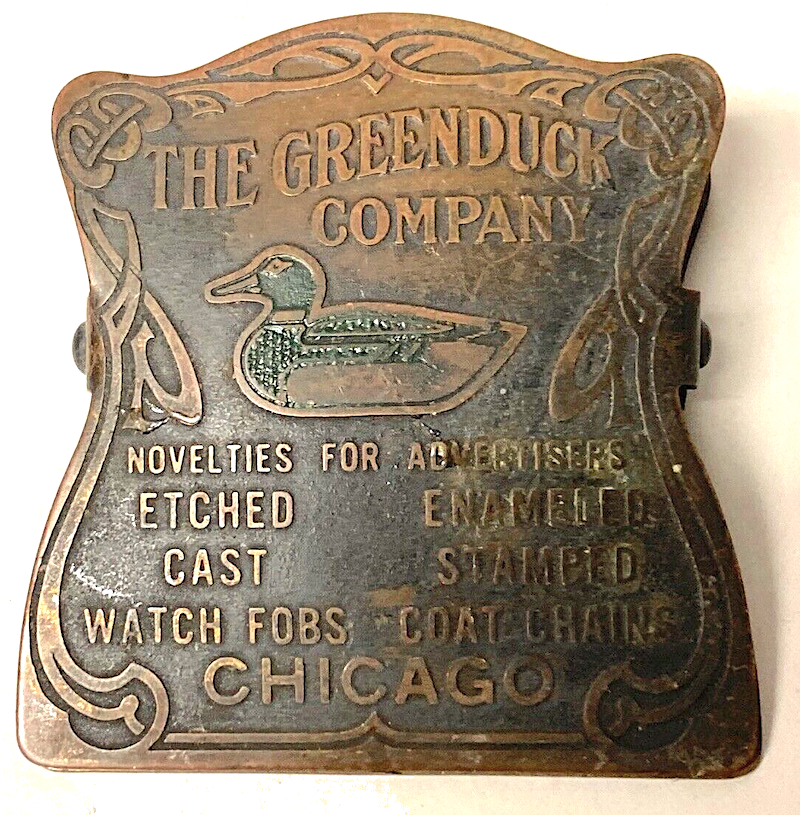

The first order of business in talking about a company called Green Duck, obviously, is the name. While quirky, cutesy animal names are almost standard operating procedure in the age of the 21st century internet start-up, this was decidedly not the case in 1906, when George G. Greenburg and Henry J. Duckgeischel organized their metal stamping business on South Clinton Street. One thing that was kind of trendy at the time, however, was combining the names of two businessmen to form a new joint entity (see John Stewart and Thomas Clark’s “Sterk MFG Co.” or Hal Elliott and Sam Goss’s “Halsam Products Co.”). And so, GREENburg and DUCKgeischel went with the most amusing moniker mashup available to them: “GREENDUCK!” This was originally spelled as a single word, but evolved into two once people lost track of the origin story and focused more on the company’s mallard mascot.

Incidentally, a “green duck” was also a popular new culinary term during this same period in the early 1900s, referring to ducklings that were fattened up and kept immobile before butchering, creating a supposedly more succulent “table delicacy”—like the waterfowl version of veal. I’m not sure if that’s a connotation the company would have found advantageous for selling medals and badges, but there you go.

Incidentally, a “green duck” was also a popular new culinary term during this same period in the early 1900s, referring to ducklings that were fattened up and kept immobile before butchering, creating a supposedly more succulent “table delicacy”—like the waterfowl version of veal. I’m not sure if that’s a connotation the company would have found advantageous for selling medals and badges, but there you go.

Before going into business together, Greenburg (b. 1868) and Duckgeischel (b. 1869) had already been longtime colleagues in the Chicago firm of S. D. Childs & Co., one of the city’s oldest die sinkers and engraving businesses. Duckgeischel was the factory superintendent, while Greenburg was a manager and a standout product developer, having invented and patented a method for making “bi-metallic coins” in 1899. By 1904, Greenburg thought he had a deal in place to become one of the directors of Childs & Co., but when he wasn’t offered the stake he was promised, he took the company to court over it and basically burned all bridges on his way out the door . . . except, apparently, where it concerned Mr. Duckgeischel.

While “Duck” remained dutifully employed with Childs & Co. and would remain so for the rest of his career, he apparently maintained a soft spot for the departed Greenburg, and agreed to help him get a new engraving business off the ground, incorporating the Greenduck Company with him for $10,000 in 1906. What Duckgeischel may not have counted on is the Greenduck Company rapidly emerging as a legitimate rival to Childs & Co. in the metal novelty field—a conflict of interest that might explain why Duckgeischel’s association with Greenburg ended not long after it began. The “Duck” contributed some cash and a fun name to our story, but little more.

Meanwhile, George Greenburg—as president and driving force of the new enterprise—went to work combining his years of experience with a natural knack for schmoozing and deal making. By 1908, he’d already caught his big break, cornering an exclusive and lucrative market in the heat of a presidential election.

Meanwhile, George Greenburg—as president and driving force of the new enterprise—went to work combining his years of experience with a natural knack for schmoozing and deal making. By 1908, he’d already caught his big break, cornering an exclusive and lucrative market in the heat of a presidential election.

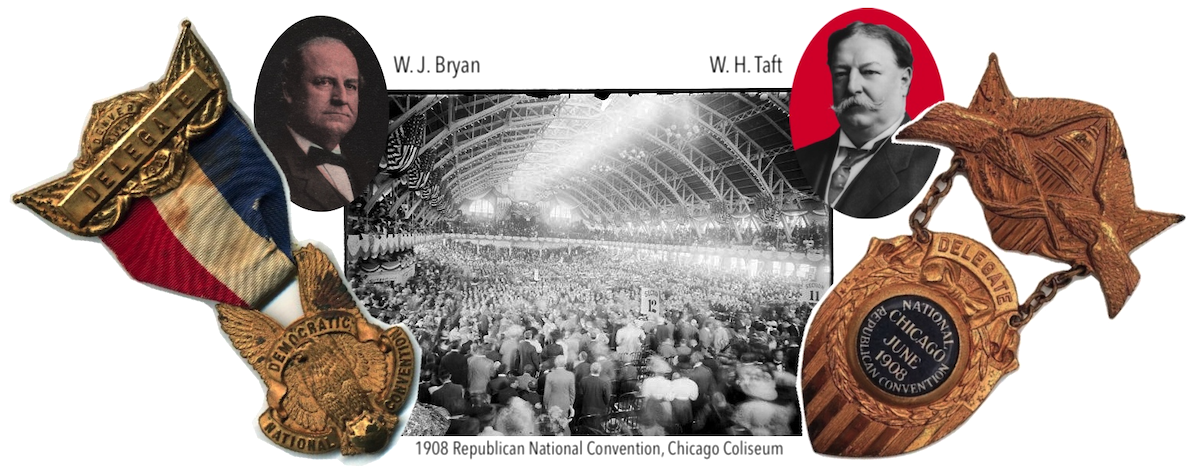

“For the first time in history, one concern has had the honor, as well as the good fortune, of making the official badges for the national convention of the two big political parties,” one newspaper reported that summer. “Both the badges for the Republican and Democratic National Convention have been made by the Greenduck company of Chicago. The badges for each are exquisite articles of rare design. In competition with all the badge makers of the country, all of whom strive for this convention work, the Greenduck company were the victors, winning the big contracts on the merits of their work submitted.”

Setting an important precedent with its first presidential hopefuls, Green Duck played things even-handed with the Republican nominee William Howard Taft and his Democratic opponent William Jennings Bryan, producing snazzy delegate badges with lots of fine, intricate detailing. The company was now officially one of the trusted guns-for-hire in political paraphernalia going forward.

By 1909, the original Green Duck headquarters at 313 S. Clinton Street had 100 workers on staff, with 50 men, 38 women, and 12 children. This forced a move the following year to a larger facility at 2127 Tilden Street (near Hoyne Avenue and Van Buren Street), where the firm continued expanding its catalog with all sorts of metal doo-dads for the political and apolitical alike.

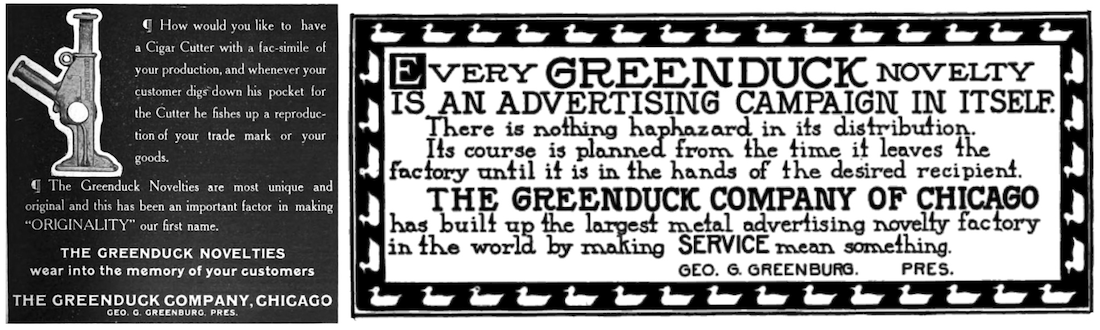

“How would you like to have a Cigar Cutter with a facsimile of your production?” asked a 1911 Green Duck ad. “Whenever your customer digs down his pocket for the Cutter he fishes up a reproduction of your trademark of your goods. . . . The Greenduck Novelties are most unique and original and this has been an important factor in making ORIGINALITY our first name. . . Greenduck Novelties wear into the memory of your customers.”

“Every Greenduck Novelty is an advertising campaign in itself,” claimed a 1916 ad. “There is nothing haphazard in its distribution. Its course is planned from the time it leaves the factory until it is in the hands of the desired recipient. The Greenduck Company of Chicago has built up the largest metal advertising novelty factory in the world by making SERVICE mean something. —Geo. G. Greenburg, Pres.”

[Greenduck Company advertisements from 1911 (left) and 1916]

To his neighbors in Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood (he lived at 915 Margate Terrace), George Greenburg was a well-off, upstanding citizen; a mild-mannered, middle-aged husband and father of two. But evidence suggests he liked to live a bit fast and loose with his Green Duck earnings.

For many years, Greenburg was secretary-treasurer of the Chicago Motor Club and personally drove a Packard in various touring events—earning himself a suspension in 1913 for “violating the rule which forbids carrying women either as passengers or observers” (I suppose his wife could have been the lady in question, but that seems unlikely). That same year, in a far more serious example of living dangerously, Greenburg was investigated by the Illinois Secretary of State for potentially “swindling” the government on a deal to manufacture official automobile license tags. Turns out, the Green Duck factory was making multiples of the same plates, creating a situation in which various motorists were driving around town in different vehicles with identical ID numbers.

Consequences were usually minimal for George, however, until the onset of World War I, when his circumstances—and that of the Green Duck Co.—seemed to change. Suddenly, the idea of using large reserves of metal to make self-described “novelties” didn’t sound like a great pitch to clients or the general public. Greenburg tried to argue the case from a propaganda perspective, even delivering a speech on the subject at the 1918 convention of the National Association of Advertising Specialty Manufacturers. His address was titled, “Is Our Business an Essential Industry—Essential to the Winning of the War?”

Consequences were usually minimal for George, however, until the onset of World War I, when his circumstances—and that of the Green Duck Co.—seemed to change. Suddenly, the idea of using large reserves of metal to make self-described “novelties” didn’t sound like a great pitch to clients or the general public. Greenburg tried to argue the case from a propaganda perspective, even delivering a speech on the subject at the 1918 convention of the National Association of Advertising Specialty Manufacturers. His address was titled, “Is Our Business an Essential Industry—Essential to the Winning of the War?”

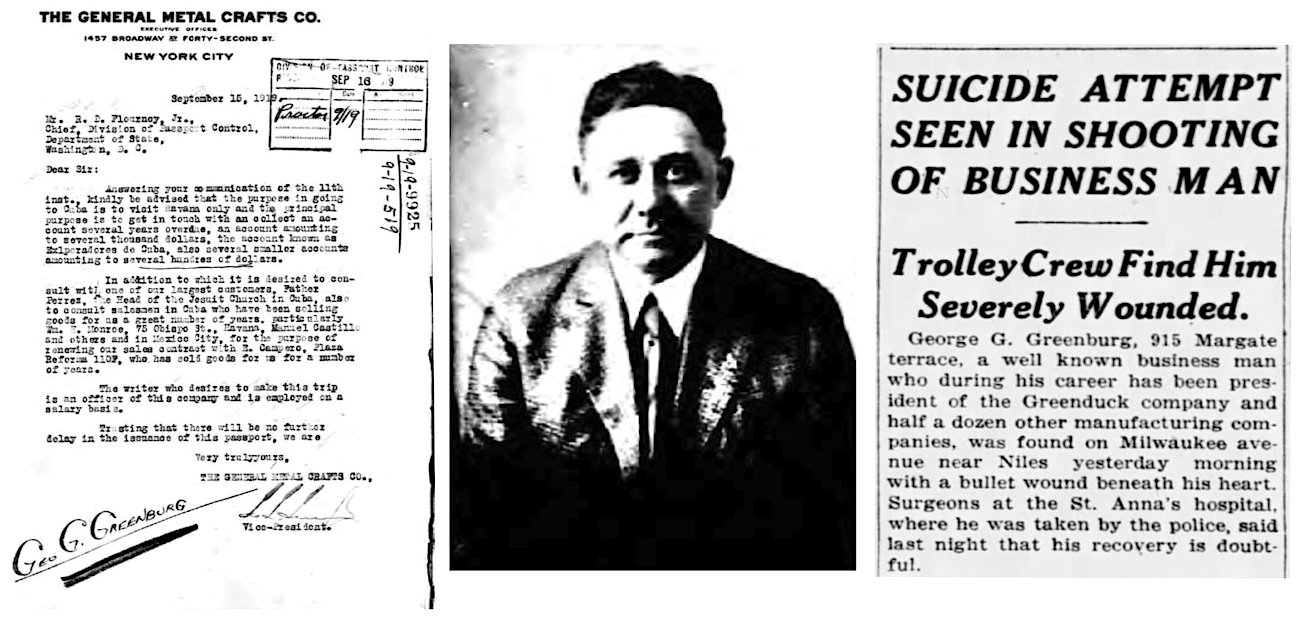

The war was over by the time anybody figured out the answer to that question, but Greenburg seemed to be at the beginning of a downward spiral, losing much of his fortune over the next few years thanks to ill-advised forays into other ventures. In 1919, while still president of Green Duck, George traveled to Cuba as a representative of another firm, the General Metal Crafts Company of New York, explaining to U.S. Passport officials that the principal purpose of his trip was to “collect an account several years overdue; an account amounting to several thousands dollars.” Yes, Meyer Lansky and Lucky Luciano hadn’t brought the mafia to Cuba yet, but this business trip still looks like the odyssey of a desperate man in over his head.

Two years later, sinking in his own debt, Greenburg reluctantly sold the Green Duck Company to outside interests. Shortly thereafter, on March 30, 1922, he was found leaning against a tree on Milwaukee Avenue, near Niles, with a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the chest. He died a few days later at the age of 54.

Police on the scene eventually determined that Greenburg had taken his own life “because of financial worries. . . Several concerns once headed by Greenburg had failed. His wealth, once reported to be more than half a million dollars, had disappeared. So on the records of the Irving Park police station the sentence ‘attempted to commit suicide while despondent’ will be inscribed.”

[Left: George Greenburg’s 1919 letter to the U.S. Passport office, explaining the reasons for his trip to Cuba. Center: Greenburg’s 1919 passport photo, age 51. Right: Tribune report of Greenburg’s suicide attempt in 1922. He died shortly afterwards.]

Part II. The Duck Quacks Back

“Any metal worker can make a copy of your emblem, but it takes Master Crafters to produce Individuality. The products of our great workshop include fraternal badges, advertising novelties, souvenirs, identification tags—in fact anything that can be made of metal, from pure gold to iron. And into every piece is moulded the skill and individuality of our Master Crafters.” —Green Duck ad, 1922

Considering the dismal end that marked the close of Green Duck’s first chapter, it’s somewhat remarkable just how quickly and profoundly things turned around under the company’s new ownership.

Heading this group was William U. Watson (b. 1883), an engineer who studied at the Armour Institute of Technology and served as general manager of the Sunderland Manufacturing Co. before taking over the presidency of Green Duck in 1921. Joining him were vice president R. C. Wheeler and secretary Lawrence E. Duffy, a former sales manager for Life Savers candy. In short order, these seasoned pros established a new subsidiary business, the Green Duck Metal Stamping Company, and absorbed the patents, factories and machinery of two rival Chicago firms: the Sanitary Fibre Company and J. L. Lynch Company. The latter acquisition was particularly important, as James L. Lynch owned the 1917 patent for making lithographed pinback buttons, a new method that was far cheaper and easier to replicate than the traditional celluloid buttons Green Duck had been making.

Heading this group was William U. Watson (b. 1883), an engineer who studied at the Armour Institute of Technology and served as general manager of the Sunderland Manufacturing Co. before taking over the presidency of Green Duck in 1921. Joining him were vice president R. C. Wheeler and secretary Lawrence E. Duffy, a former sales manager for Life Savers candy. In short order, these seasoned pros established a new subsidiary business, the Green Duck Metal Stamping Company, and absorbed the patents, factories and machinery of two rival Chicago firms: the Sanitary Fibre Company and J. L. Lynch Company. The latter acquisition was particularly important, as James L. Lynch owned the 1917 patent for making lithographed pinback buttons, a new method that was far cheaper and easier to replicate than the traditional celluloid buttons Green Duck had been making.

“President Watson is reported to estimate that the 1923 business of his firm will be 800 percent greater than that of last year,” Chicago Commerce reported at the time, adding that Green Duck now had the capacity to produce a million pieces per day. “The company also has a contract for 1923 to deliver 20,000,000 buttons to the Red Cross. Of course these same masterful manufacturers expect to have quite a few buttons circulating for the presidential campaign of 1924.”

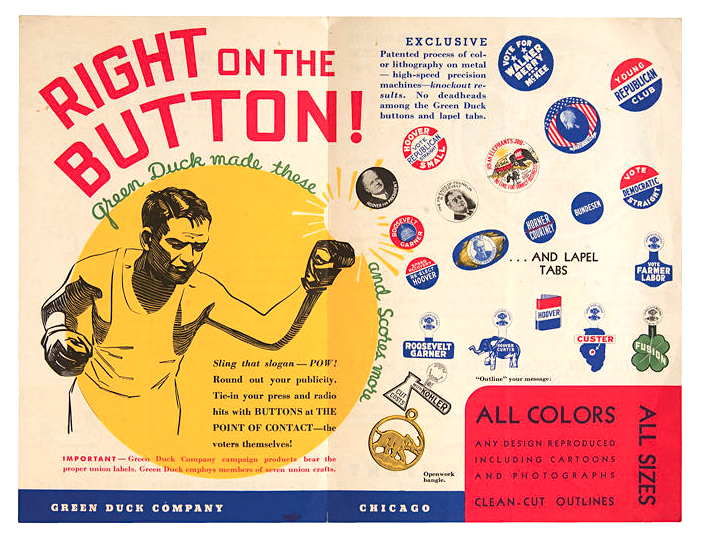

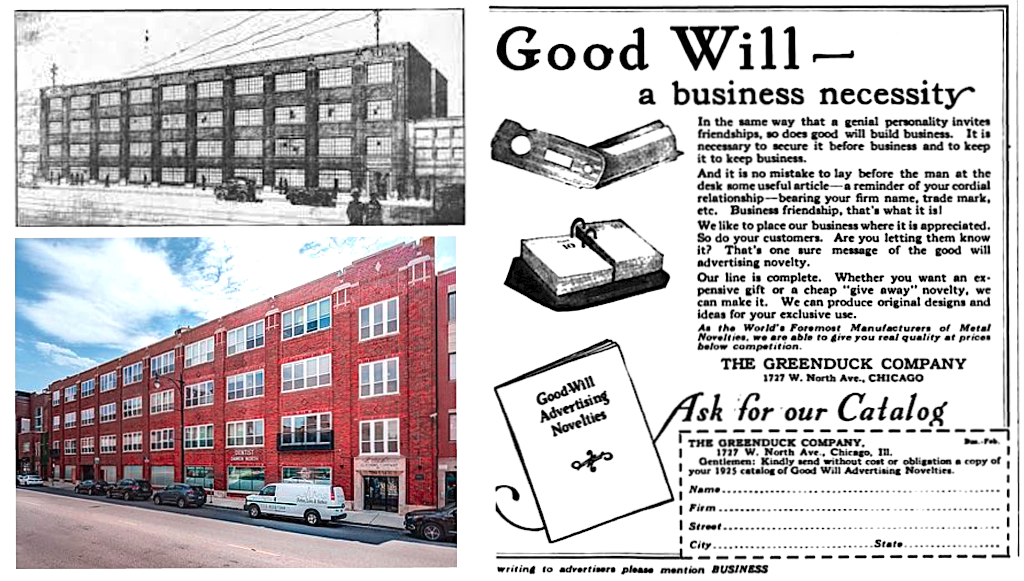

Perhaps recognizing where George Greenburg had gone wrong in the past, Watson and his crew didn’t rest on their laurels. Lynch’s lithograph technology and a new primary headquarters at 1727 W. North Avenue opened up the opportunity to dive headfirst into any and all new orders, with fewer limits on design. A new Chicago ad agency was also hired, Lucien M. Brouillette, to help Green Duck better express the “essential” values of its otherwise functionless products.

[Left: Former Green Duck factory at 1725 W. North Ave., 1920s vs. today. Right: 1925 ad for Greenduck’s “Good Will Advertising Novelties”]

“Good Will—a business necessity,” read a 1925 ad. “It is no mistake to lay before the man at the desk some useful article—a reminder of your cordial relationship—bearing your firm name, trade mark, etc. Business friendship, that’s what it is! . . . Whether you want an expensive gift or a cheap ‘give away’ novelty, we can make it. We can produce original designs and ideas for your exclusive use.”

After the market crash of 1929, when many of its competitors went belly up, Green Duck, naturally, stayed afloat. Sometimes it required promotional gimmicks, like having their own showcase inside the Hall of Science at the 1933-34 Chicago World’s Fair, where visitors could buy exclusive souvenir spoons—some sterling, some nickel, and some Dirigold. Client loyalty was the bigger separator, though, and while Green Duck maintained its unbiased approach to political electioneering, the company did take at least take one stance when it came to labor unions.

Early on in his tenure, William Watson had seen one of Green Duck’s oldest rivals—New Jersey’s Whitehead-Hoag Company—damaged by labor skirmishes, and he wisely took advantage of the situation by positioning Green Duck as the worker-friendly alternative in the button business. Since it was common for union members to receive new pinbacks every month to signify their good standing, this was a particularly valuable demographic to lock down.

“A complete knowledge of union requirements puts us in a position to offer you superior merchandise at exceptional prices,” read a Depression-era Green Duck ad. “Dues buttons are an important item to every union local. We are supplying hundreds of locals throughout the country and would appreciate a chance to serve you.”

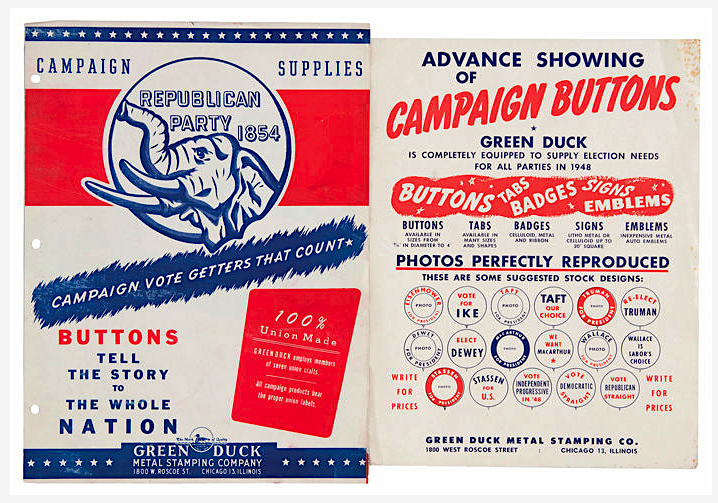

Green Duck signed agreements of good faith with the Metal Polishers’ International Union, Metal Workers International Union, Photo Engravers International Union, International Association of Machinists, and Type Printers’ International Union, and these relations remained significant for many years, as evidenced by the union labels inside the 1936 FDR button in our museum collection.

Green Duck signed agreements of good faith with the Metal Polishers’ International Union, Metal Workers International Union, Photo Engravers International Union, International Association of Machinists, and Type Printers’ International Union, and these relations remained significant for many years, as evidenced by the union labels inside the 1936 FDR button in our museum collection.

You’ll notice that our FDR pinback also includes a mention of James Lynch’s 1917 litho patent (No. 1,215,675). Not referenced, however, is a key tech innovation of the early 1930s, as Green Duck’s new quick enameling processes “enabled vast quantities of buttons to be stamped out of lithographed sheets bearing as many as 400 impressions.” Some of these designs, such as the portrait of Roosevelt, were merely adapted from existing campaign materials, but others were born more directly from the creative minds of the Green Duck art department, who could now produce thousands of new buttons, almost in real time, inspired by the latest developments from the campaign trail.

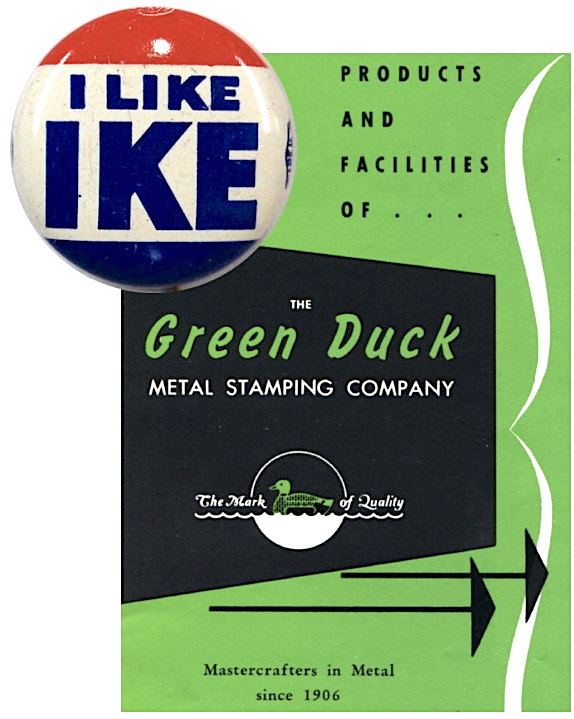

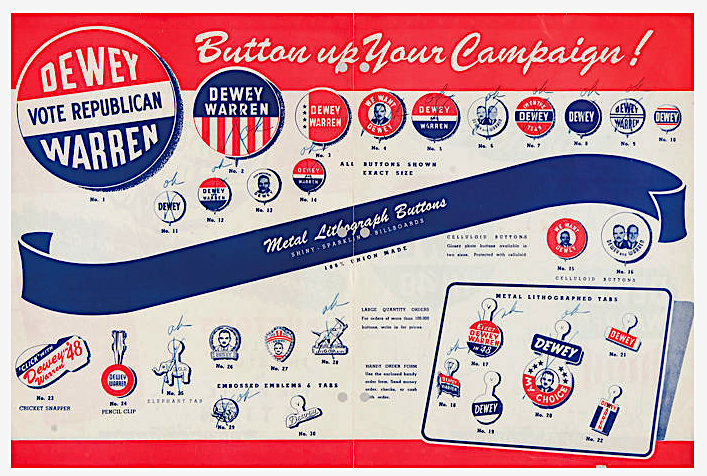

Savvier politicians like Republican Wendell Wilkie recognized how to weaponize this, and rather than just ordering a few “Vote Wilkie” buttons from Green Duck, his staff continued to order new designs and slogans throughout the 1940 presidential race, creating the equivalent of pre-internet political memes, as noted in the intro to this article. Wilkie’s barrage of buttons wasn’t enough to give him a prayer of beating Franklin Roosevelt, but it set the tone for the high-point of campaign button relevance in the ‘40s, ‘50s, and ‘60s, when slogans like “I Like Ike” went from catchy to iconic.

[Top Left: Roosevelt “A Gallant Leader” poster, 1936, featuring the same portrait used in Green Duck campaign buttons. Top Right: Selection of 1940 presidential campaign buttons. Bottom: A selection of specially designed buttons for the 1936 presidential campaign of Republican Alf Landon and VP candidate Frank Knox]

Interestingly, Green Duck’s last association with Franklin D. Roosevelt was a somewhat controversial one. In 1944, Roosevelt’s War Production Board granted 100 tons of surplus steel—during a time of rationing—to the Green Duck Company for the purpose of making “buttons and tabs for religious, educational, charitable, patriotic, safety, and political organizations.” Reporters seized on the story and suggested the whole arrangement was an excuse for Green Duck to shamelessly make “I Want FDR Again” re-election buttons. William Watson strongly denied these accusations, even though plenty of those exact buttons were clearly made. “Not a button has been ordered from us,” he said, “and if any had been ordered or were being made anywhere, I’m sure we’d know about it.”

Watson added that Green Duck’s wartime plans included making 50 million buttons and tabs for the Red Cross and 7 to 8 million more for community funds and chests. The company also had a contract to produce brass metal clickers, called “crickets,” which were used by the U.S. Army to signal codes to one another. After the war, the same sort of devices would be used for animal training.

Watson added that Green Duck’s wartime plans included making 50 million buttons and tabs for the Red Cross and 7 to 8 million more for community funds and chests. The company also had a contract to produce brass metal clickers, called “crickets,” which were used by the U.S. Army to signal codes to one another. After the war, the same sort of devices would be used for animal training.

Turning 60 in 1943, Watson may have seen WWII as the final big challenge of his long journey with Green Duck. In 1945, he bowed out of the business, selling the firm to an investment group led by John E. DeWolf, Jr. The new owners came in with a plan similar to the one Watson had ushered in back in the ‘20s—to expand the business and capitalize on an expected big demand for metal novelties in post-war America.

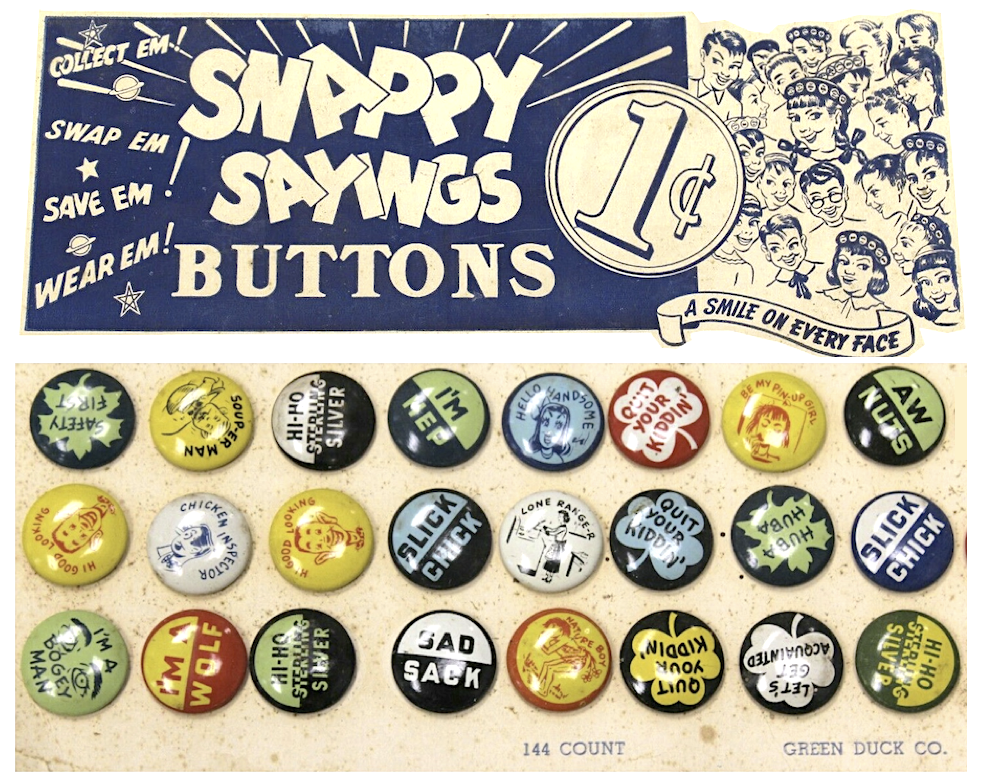

[Green Duck’s “Snappy Savings Buttons” sold for 1-cent a piece in 1949]

Part III. A Hundred Million Walking Billboards

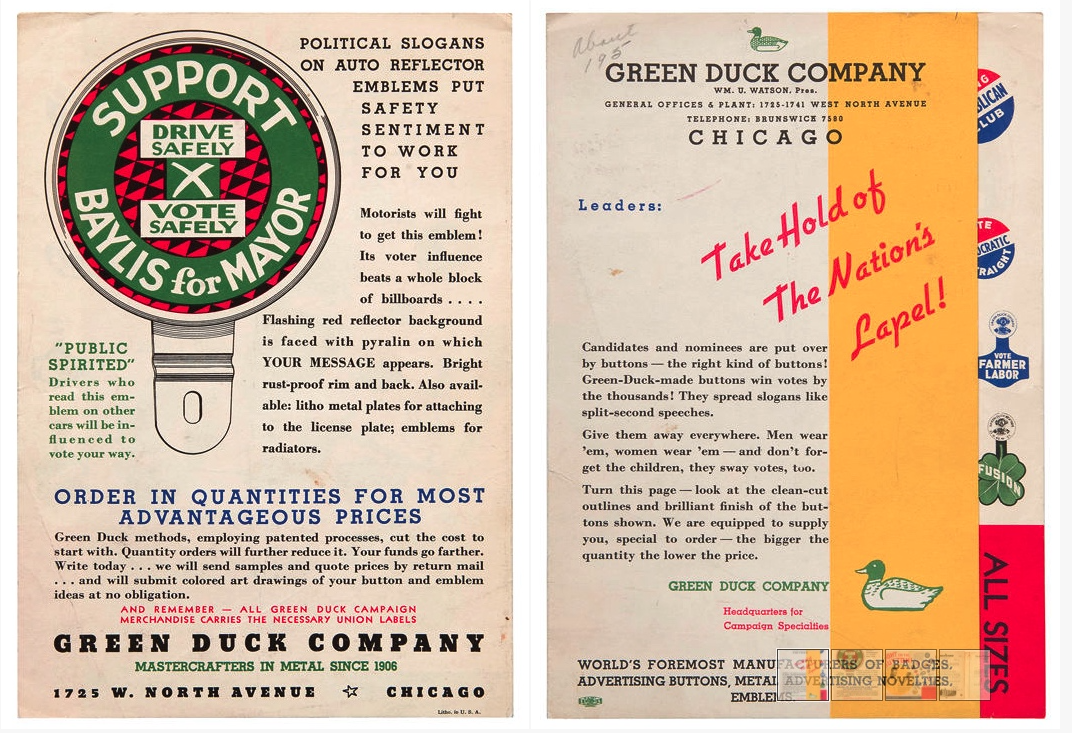

“Take Hold of the Nation’s Lapel! Candidates and nominees are put over by buttons—the right kind of buttons! Green-Duck-made buttons win votes by the thousands! They spread slogans like split-second speeches. Give them away everywhere. Men wear ’em, women wear ’em—and don’t forget the children, they sway votes, too.” —Green Duck sales flyer, 1940s

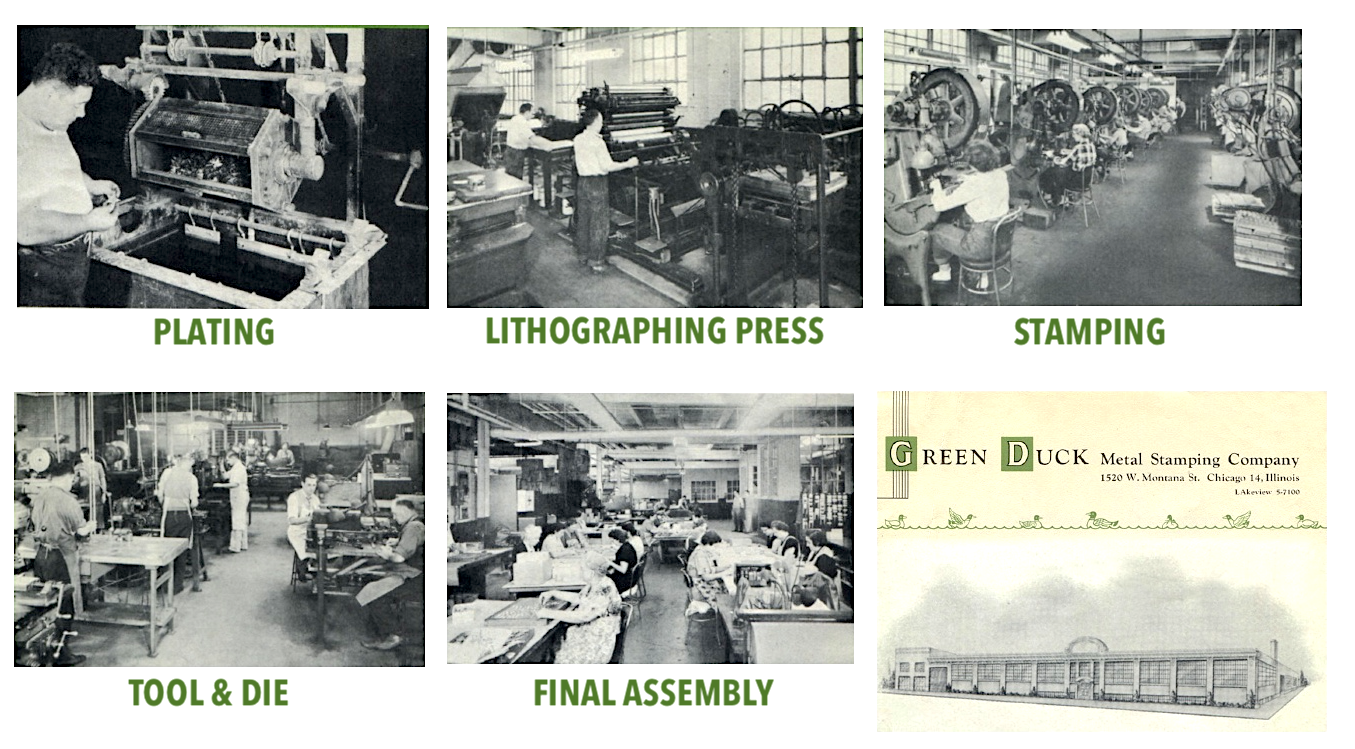

During and after the war, Green Duck’s manufacturing plant was located at 1800 W. Roscoe Street, but by 1951, they relocated again to a bigger factory at 1520 W. Montana Street in Lincoln Park.

This facility, which has since been demolished, included departments for plating, stamping, tool & die, litho pressing, and assembly. It would have to run at full capacity to keep up with the massive orders for the 1952 campaign season, including the legendary “I Like Ike” pinbacks made for Republican presidential candidate and eventual winner Dwight Eisenhower.

This facility, which has since been demolished, included departments for plating, stamping, tool & die, litho pressing, and assembly. It would have to run at full capacity to keep up with the massive orders for the 1952 campaign season, including the legendary “I Like Ike” pinbacks made for Republican presidential candidate and eventual winner Dwight Eisenhower.

“The consensus among leaders of the button industry is that there never has been anything like the vigor of the current campaign at this stage,” according to one syndicated news report from April of 1952. “The Green Duck Metal Stamping Company foresees a political-button volume of at least 100 million from their own shop. . . . Automatic gas-fired tunnel ovens at Green Duck have a capacity of 2,000 sheets an hour [with 400 impressions on each sheet], giving an indication of how fast they can be turned out. . . Six-hundred-ton stamping machines blank and crimp the buttons and other machines pin them. They pour into bags containing 1,000 each.”

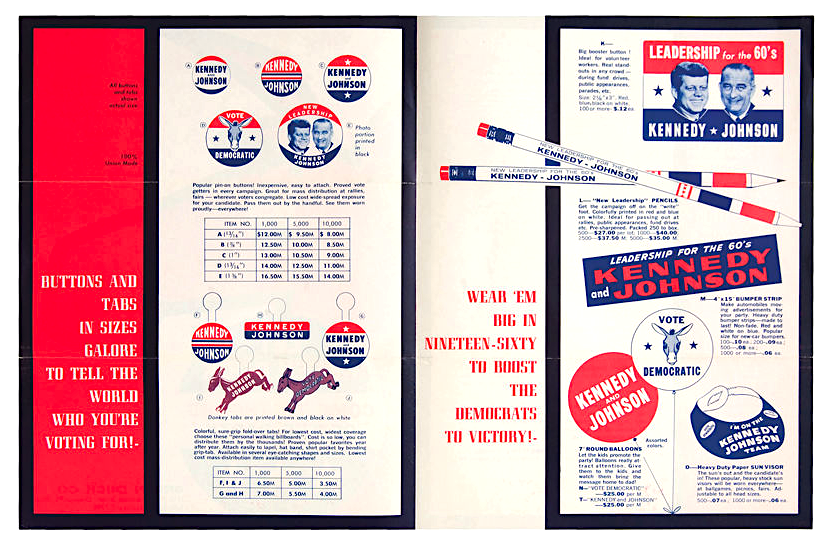

Green Duck was believed to have a hold on about 80% of the campaign button industry in the ‘50s, with smaller Chicago firms like the Union Litho Metal Corp. and L. J. Imber & Co. picking up the scraps (Imber, himself, had previously worked with Green Duck for 20 years). For Green Duck it was “strictly a large-volume business,” with most orders requiring a minimum of either 10,000 buttons or 25,000 lapel tabs. According to another 1952 featurette, “The size of the order governs the cost.” A red, white and blue 3-inch pinback might cost 15 cents each in a small batch, but the 1-inchers could go for half-a-cent each in a lot of a million or more. Since they were all made from cheap black-plate tin—the type rejected by the canning industry—costs of production were minimal. As a general rule, though, all clients were asked to pay in advance.

Inside the Montana Avenue Factory, 1952

“We insist on cash,” Green Duck’s new VP Earl Butler explained in 1952, “because we can never tell when a candidate might suddenly withdraw from the race, leaving us with thousands of dollars worth of meaningless buttons on our hands.”

Interestingly, one of the 1952 news reports notes that all button makers “steer clear of ‘derogatory’ buttons, reflecting a professed industrial pride for being artistic and in good taste, and also because they have been advised that as ‘publishers’ of buttons they might be liable for defamation.”

Interestingly, one of the 1952 news reports notes that all button makers “steer clear of ‘derogatory’ buttons, reflecting a professed industrial pride for being artistic and in good taste, and also because they have been advised that as ‘publishers’ of buttons they might be liable for defamation.”

By 1960, Green Duck was still the big player in its industry, making 24 designs each for both John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon’s campaigns; JFK’s camp, unsurprisingly, favored the portrait-style buttons a lot more than Nixon’s did.

“From the middle of August to the last week in October we were producing full tilt,” Earl Butler told the American-Statesman newspaper after Kennedy’s win, “between one million and two million buttons a day, working two shifts of 125 employees. Speed is our big problem, because when political workers get all fired up, they think they should be able to place an order at 4pm and get shipment at 2pm the same day.”

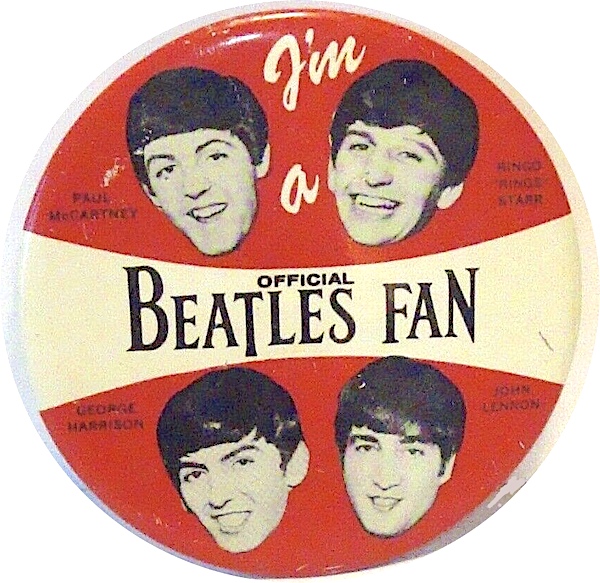

Taking into account the 1960 election plus contracts with charities and corporations, Green Duck’s estimated production of buttons and badges was still over 100 million per year, according to Butler. Political button demand wasn’t quite as hot by 1964 (LBJ was no JFK when it came to marketability), but that was more than balanced out by the cash windfall that came from selling 30 million “Beatles Fan” buttons as the Fab Four conquered America. Signing up John, Paul, George and Ringo was a bet that paid off, but when you’re talking about pressing this much metal, not every swing is going to make contact.

“It’s risky, all right, and I can’t say we’ve always guessed right,” Green Duck president Victor Milazzo told the Tribune in 1964. “We can turn out one million buttons a day, but you have to work ahead and anticipate the demand.”

“It’s risky, all right, and I can’t say we’ve always guessed right,” Green Duck president Victor Milazzo told the Tribune in 1964. “We can turn out one million buttons a day, but you have to work ahead and anticipate the demand.”

Unfortunately for Milazzo, that demand was clearly trending in the wrong direction when it came to campaign buttons. In 1968, an Associated Press story examined the waning interest in all political pinbacks, citing the competition from more effective TV advertising as well as general button fatigue among the populous—particularly conservatives who were turned off by the more aggressive or perplexing designs sported within the hippie movement. In the wake of the assassinations of President Kennedy, and now Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, being a “walking billboard” for a candidate—as Earl Butler once put it—also started to feel a tad dangerous, or at the very least, less fun.

And so, in another example of “working ahead,” Milazzo sold Green Duck in the summer of ’68 to Ero Industries, a Chicago firm that had originally specialized in car seat covers.

IV. Sinking in the Mississippi Mud

Ero’s ambitious president, Martin N. Sandler, rolled into the 1970s with big plans. He set up Ero with new kitchen appliance and sporting goods divisions, and broke off part of Green Duck into a specialized coin and medal firm called the Lincoln Mint (714 W. Monroe St.), intended to compete directly with the dominant Franklin Mint in the world of limited-edition collectibles. Despite Ero’s Chicago roots, however, the decision was made to move Green Duck’s button manufacturing out of state, to a more modern, cost-efficient plant in Hernando, Mississippi. After 65 years, Chicago would no longer be the nation’s pinback headquarters.

Around the time of the move, in 1970, Green Duck was supposedly on an upswing, with assistant sales manager Marsha Geraghty telling the Associated Press, “We’re expanding all the time, buying new machinery, looking for new ways to make buttons and slogans to put on them. We’re growing constantly and there’s no end in sight.”

Around the time of the move, in 1970, Green Duck was supposedly on an upswing, with assistant sales manager Marsha Geraghty telling the Associated Press, “We’re expanding all the time, buying new machinery, looking for new ways to make buttons and slogans to put on them. We’re growing constantly and there’s no end in sight.”

When the 1972 election rolled around, though, Green Duck’s first campaign season in Mississippi proved mighty disappointing. Ira Urbach, the new head of Ero’s Green Duck division, said he believed his firm still held 50-60% of the political button market, but that profits were much lower than expected. Ero chief Martin Sandler added that there were “sharply decreased orders coming from both the Republican and Democratic parties,” and that sales into October hadn’t topped $400,000, compared with $1.2 million in the 1968 race.

Ero Industries’ hopes of becoming a powerful conglomerate blew up, and Green Duck was sold yet again in the mid ‘70s, this time to investors Elliot Sklar of New York and Ronald Stein of Chicago, who continued operating the Mississippi button factory.

[Elliott Sklar, who owned the Green Duck Corporation in its later years]

In the ‘80s and ‘90s, Green Duck shifted into arenas that were almost as debaucherous as politics, producing Mardi Gras doubloons and slot machine tokens and poker chips for riverboat gambling companies and casinos.

“We made three-and-half million dollars in tokens for Donald Trump’s Taj Mahal just before it opened,” operations manager Roy Houston told the McComb Enterprise-Journal in 1991, noting that Trump seemed determined not to pay them for their work. “It was four months before we got paid, but we were paid,” he said.

Elliot Sklar sold Green Duck to a British firm in the 1990s, and the Mississippi factory was later abandoned. All remaining signs of the business evaporated by 2004, just shy of its 100th birthday. Well, almost all signs.

In 2008, construction crews tearing down the old Mississippi plant unearthed a treasure trove of highly collectible “Playboy Bunny” gambling chips from the defunct Playboy Casino in Atlantic City. The chips—which Green Duck had been contracted to break down and re-use for their metal after the casino folded—had somehow wound up buried under a slab of concrete, all fully in tact. Because the same type of Playboy chips were selling for big money on eBay at the time, a mad dash suddenly began on the construction site, as people grabbed up the buried chips and tried to cash them in. This ultimately flooded the market and rendered all the chips collectively worthless. Some treasures are better left buried.

In 2008, construction crews tearing down the old Mississippi plant unearthed a treasure trove of highly collectible “Playboy Bunny” gambling chips from the defunct Playboy Casino in Atlantic City. The chips—which Green Duck had been contracted to break down and re-use for their metal after the casino folded—had somehow wound up buried under a slab of concrete, all fully in tact. Because the same type of Playboy chips were selling for big money on eBay at the time, a mad dash suddenly began on the construction site, as people grabbed up the buried chips and tried to cash them in. This ultimately flooded the market and rendered all the chips collectively worthless. Some treasures are better left buried.

Other treasures, like Green Duck’s seemingly endless contributions to the pinback universe, seem to keep on giving as time goes by. Collectible values may rise and fall, but from political hopefuls to punk rockers to Playboy bunnies, Green Duck, even in its retirement into vintagedom, is still spreading slogans like split-second speeches.

Sources:

“Scanning Around With Gene: Clicking at the Green Duck” – CreativePro.com

“Lithograph Pinback Buttons (And One Unique Contraption)” – BaseballPinbackButtons.wordpress.com

“Green Duck” – Busy Beaver Button Museum

“Tokens” (S. D. Childs & Co. history), by David E Schenkman, 2013

“One Concern Makes Both Convention Badges” – Fort Collins Express, July 1, 1908

“Greenburg vs. S. D. Childs & Co.” – Appellate Courts of Illinois, 1909

“Duplicate Auto Licenses?” – Moline Daily Dispatch, Oct 3, 1913

“National Board Bars Greenburg” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 2, 1913

“Chicago Form Company v George G. Greenburg and Henry Duckgeischel,” Appellate Courts of Illinois, 1914

“Business Convention for Specialty Manufacturers” – Printers Ink, Sept 26, 1918

“Suicide Attempt Seen in Shooting of Businessman” – Chicago Tribune, March 31, 1922

“Button, Button, Who’s Got the Button? Right Here on Chicago’s Own Breast” – Chicago Commerce, Aug 18, 1923

“To the Metal Trades Department of the American Federation of Labor in Convention Assembled” – Our Journal, Dec 1924

“Full Dirigold Exhibit” – Kokomo Tribune (Indiana), May 24, 1933

“‘I Wan To Be a Captain’ Tag Sales Boom in Slap at Elliott” – Indianapolis News, Oct 2, 1940

“WPB Grants 100 Tons of Steel on Button Job” – Chicago Tribune, June 15, 1944

Henry J. Duckgeischel (obituary) – Chicago Tribune, Jan 28, 1947

Green Duck Metal Stamping Co. catalog – 1952

“Eisenhower Leading Taft in Political Button Race” – Muncie Star, April 15, 1952

“Sure Thing for 1952: the Button Business” – Holdrege Daily Citizen (Nebraska), May 27, 1952

“Firms Zips Up Production of New Political Buttons” – Boston Globe, April 4, 1956

“Green Duck Strictly for Green Duck” – American-Statesman (Austin, TX), Nov 20, 1960

“Pin Point Poll Shows All Even” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 3, 1964

We Made Our Deal: A Magical Mini-Tour of the Official Beatles Fan Button from 1964, by Terry Crain, 2019

“Campaign Buttons Losing Appeal with the Public” – Kansas City Star, Sept 8, 1968

“Button Firm Has Motto: Be Prepared” – Miami Herald, Aug 6, 1968

“Medal Firms are Making a Mint” – Kansas City Star, July 6, 1969

“Button Industry Expands with Times Looking Bad” – Clarion-Ledger (Jackson, MS), June 19, 1970

“102 Years Experience by Father-Son” – McHenry Plaindealer (Illinois), Feb 19, 1971

“Button Headquarters” – Clarion-Ledger (Jackson, MS), June 6, 1971

“Political Buttons Losing Their Zip?” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 19, 1972

“Green Duck’s More Than Buttons; It’s a Business” – Clarion-Ledger (Jackson, MS), Jan 11, 1977

“Hernando Firm Finds Mint in Riverboat Casino Contract” – McComb Enterprise-Journal (Mississippi), Jan 28, 1991

“An Unwelcome Jackpot” – Honolulu Star-Bulletin, May 4, 2008

I have a small square “pin” with Greenduck on the attachment circle, which screws on to the back of the “pin”. The pin itself has a blue X in the middle on a white cirdular background, surrounded by a red circle. The corners outside of the circle are the same blue as the X. I assume it is a lapel pin as other than a little prong that would help old it in position, there is just the screw and screwback which must have fit into a lapel slit. Can anyone give me information about this?

I have an Abraham Lincoln fob from you guys and was wondering if you could tell me something about it

I found a pin with The Old Duck Co, name on the back in my mother collectables. It is a 3/4 x 3/8′ pin with a horizontal pin on the back. White back ground, red boarder and a single blue star in the middle. I’m sure is is quite old. Could you please tell me what it might represent? I would like to donate in to the museum.

I have what looks like a copper cufflink. It has a monogram on it that looks like “HB.” Member of the HB idea club. Keep the quality up. Looks like an old copper penny in color similar to the Greenduck medallion shown above.. Any ideas?

I have a medallion (“dog tag”) for the Military Order of the Devil Dogs that is made by the Green Duck Co Hernando MS. Just another product they made.

I have some Green duck tokens that have a picture of a mouse on one side and a picture of what appears to be Tarzan on the other, On the Tarzan side it says “charter member”. Any idea what they were for and if the hold any value?

Have 2 metals there pin on.

#1march 9th 1952

#2 June 21st 1953

They both say Greenduck Co. on top and Chicago on the bottom, one is silver edge white with a griphen/lion and the other one is copper/gold with the same middle part

I have a button that is from Green Duck Co. Chicago that is “A Gallant Leader Franklin D. Roosevelt “.

What is it worth?

I haven’t been able to find any information about some “In Service” pins for USN, Marines, Coast Guard, Army and Air corps Greenduck pin back buttons. There are four mint marks with a Greenduck Co. Chicago on the back. I was told they were WWI pins my great grandfather had. Any info would be greatly appreciated.

I have a metal cream color 51/4 oval with make our state 100% union on top with lets go on the bottom with a 4 1/4 red refector in the middle with a small local 115. I think it was made to bolt top a license plate. Do you know what year it was made

Thank you

My name is Donna Butler Uhlig…my Father Earl Butler was Sales Manager at Green Duck from approximately 1952 to 1968..My Brother and I grew up spending Saturday mornings with my Dad at the plant.We were fascinated by the metal stamping machine and the rolls of celluloid traveling down the line to be cut and stamped into buttons…the only thing better was rummaging through the sample drawers where examples of each product were kept. We never tired of looking at all the amazing coins..keychains..and buttons. This truly was an amazing company.

I have a Green Duck stamped badge that reads “US Postal Employee”. I have never seen one like it. Anyone ever seen anything like that?

I have a state farm pocket watch made by greenduck, I want to know more about it, it’s still in working condition

My father, Stanley Bush, worked for Green Duck as a tool and die maker after WWll.

My mother used to pin the buttons. I still have a cloth bag with Green Duck’s name on it which held the buttons. After my parents passed away I found a solid metal paper weight Duck. Wonderful article.

Looking for contact with anyone from Green Duck, to find out who/engraver that produced the Mark Twain Series slot machine premium Silver Strike. Interested in purchasing the molds

I have a brass or bronze campaign pin with cameo type profiles of Franklin Roosevelt and John Garner. I would like to know the year of this pin. I could send a picture if I hear from you. On the back of the pin, Green Duck Co, Chicago is imprinted with two hallmarks as well.

Sorry, I wasn’t able to upload photos. The fob was mfg’d by Greenduck in 1920.It says Chicago 1920 and then IRFA below that and IRSMA below that.

What can you tell me about this fob I have…specifically what do the initials I.R.F.A. and I.R.S.M.A. stand for?