Museum Artifact: Indestro Bottle Capper, 1920s

Made By: Indestro MFG Co., 3429 W. 47th St. [Central MFG District] / Duro Metal Products, 2649 N. Kildare Ave. [Hermosa]

When Gertrude McNaught Odlum died in 1992, aged 96, she was widely remembered as an award-winning breeder of dairy cows, owning a pair of multi-million dollar farms in the Chicago suburbs (“Rolling Acres” and “Odlum Farm”). Far less publicized, unfortunately, were her accomplishments as the matriarch of one of the largest tool and hardware manufacturers in the country. Blue ribbon bovines aside, this was a big city businesswoman, through and through.

The Duro Metal Products Company and its longtime sister/subsidiary business, Indestro Manufacturing, both had roots dating back to World War I, and Gertrude had been there quite literally from the beginning. Born in Chicago to German immigrant parents in 1895 (maiden name: Gertrude Ksionzek), she got married at 18 to a local businessman named Norris F. McNaught, and was by his side in 1917 when he organized the Duro Metal Products Co. on Ohio Street with another toolmaker named William H. Odlum.

The Duro Metal Products Company and its longtime sister/subsidiary business, Indestro Manufacturing, both had roots dating back to World War I, and Gertrude had been there quite literally from the beginning. Born in Chicago to German immigrant parents in 1895 (maiden name: Gertrude Ksionzek), she got married at 18 to a local businessman named Norris F. McNaught, and was by his side in 1917 when he organized the Duro Metal Products Co. on Ohio Street with another toolmaker named William H. Odlum.

Fifty years later, a widowed Gertrude—by then a longtime secretary/treasurer of Duro Metal—wound up marrying Odlum, too, making her a full partner in the company in more ways than one. . . . But I think maybe we’re getting a little ahead of ourselves.

To properly relate this unique story to the specific artifact in our museum collection, we really have to start a couple thousands miles away, in Portland, Oregon, where the “Indestro” half of the equation actually began.

Part I: The Indestro MFG Co.

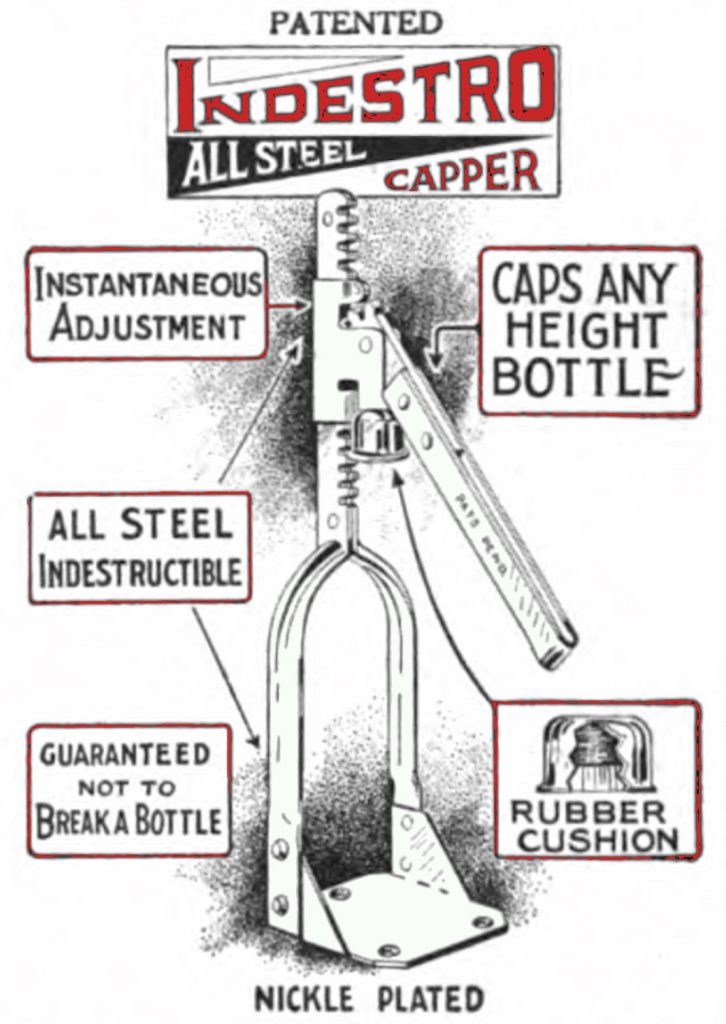

While Duro Metal Products was making a wide variety of “precision tools” from the outset, the Indestro Manufacturing Company started out independently with just a single product to its credit: a bottle capping device.

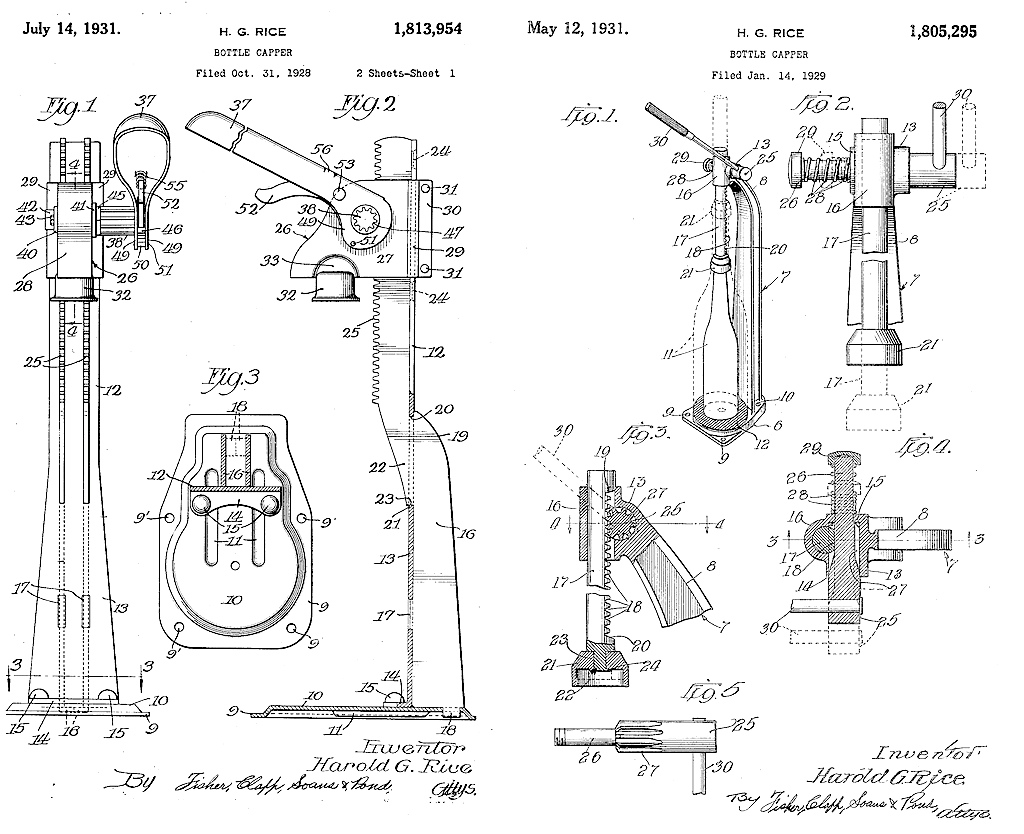

The first patent for the “Indestro All Steel Capper” was approved in February of 1918, and credited to a Portland based inventor named Harold G. Rice. Born in 1876, Rice was already in his 40s by this point, and was a respected man in the community; operating the Rice-Penne supply company in Portland’s busy Front Street wholesale district, and serving as a captain in the Oregon National Guard during the Great War.

The first patent for the “Indestro All Steel Capper” was approved in February of 1918, and credited to a Portland based inventor named Harold G. Rice. Born in 1876, Rice was already in his 40s by this point, and was a respected man in the community; operating the Rice-Penne supply company in Portland’s busy Front Street wholesale district, and serving as a captain in the Oregon National Guard during the Great War.

It wasn’t until the war was over, incidentally, that Rice seemed to seriously consider the wider potential for his bottle capper as a legit business enterprise. From his perspective—and the U.S. patent office seemed to agree—there was no comparable tool available on the market. The 16-inch tall steel appliance operated on a ratcheting lever, with no required screws or bolts. Its adjustability meant it could squeeze a cap down on any size and style of bottle—from ketchup to beer—and the rubber cushioning in the capping segment made it nearly impossible to over-stress and break the glass (a common problem during the era). This sort of item could be of interest to the general public, but it was more appealing to owners of groceries, breweries, or fellow merchants like Rice himself—anyone who’d ever been frustrated with the difficulty of sealing a bottle quickly and effectively.

Rice was confident he could sell his product, but the actual manufacturing and distribution of these heavy metal contraptions wasn’t gonna be cheap. What was a guy to do? (It’s worth noting here that the G. in Harold G. Rice literally stood for “Guy”).

[1931 patent drawings of Harold Rice’s Bottle Capper includes some new additions to a device he’d first patented in 1918]

[1931 patent drawings of Harold Rice’s Bottle Capper includes some new additions to a device he’d first patented in 1918]

Well, in 1921, Harold decided to swing for the fences. He uprooted his business and moved, with his wife and three children, from their Pacific Northwest comfort zone to the comparative chaos of Jazz Age Chicago. His entire motivation, it seems, was to manufacture and sell Indestro cappers from a more convenient center of trade.

In that first year in Chicago, Rice (with some financial aid from his old Portland business partner Landor Penne) made the most of a modest budget. He secured space in a factory at 310 South Canal Street, and with three rented punch presses and his own dies, he started building up a backstock of bottle cappers.

In that first year in Chicago, Rice (with some financial aid from his old Portland business partner Landor Penne) made the most of a modest budget. He secured space in a factory at 310 South Canal Street, and with three rented punch presses and his own dies, he started building up a backstock of bottle cappers.

The company, in these early stages, was known as the “Sure Seal Bottle Capper Co.,” but it was the Indestro trademark that really resonated; a clever reference to the “indestructible” nature of the nickel-plated capper, as well its ability to prevent the destruction of your various fragile bottles.

In an ironic twist, the factory in which the product was made proved far less durable, as a fire in 1922 completely wiped out the entire operation. Undeterred, Rice started over from scratch, spending the next two years in a space at 552 West Harrison Street, followed by a five-year stint at 2650 Coyne Street in Logan Square. Coyne Street is known as Belden Avenue today, and that building is still standing, converted into posh lofts.

[Former Indestro MFG Co. location at 2650 Coyne St. / Belden Ave]

[Former Indestro MFG Co. location at 2650 Coyne St. / Belden Ave]

Anyway, to generate public interest and distribution in the ’20s, Rice used his wholesale background to partner with Chicago suppliers like E. M. Blumenthal & Co., which happily sold the Indestro capper and advertised it in national trade publications such as Hardware Dealers, Good Hardware, and Brewers Journal. The average retail price was usually no more than a dollar or $12 for a dozen (roughly $15 per capper after inflation)—hardly a huge investment considering the thousands of bottle caps it might secure in its lifetime.

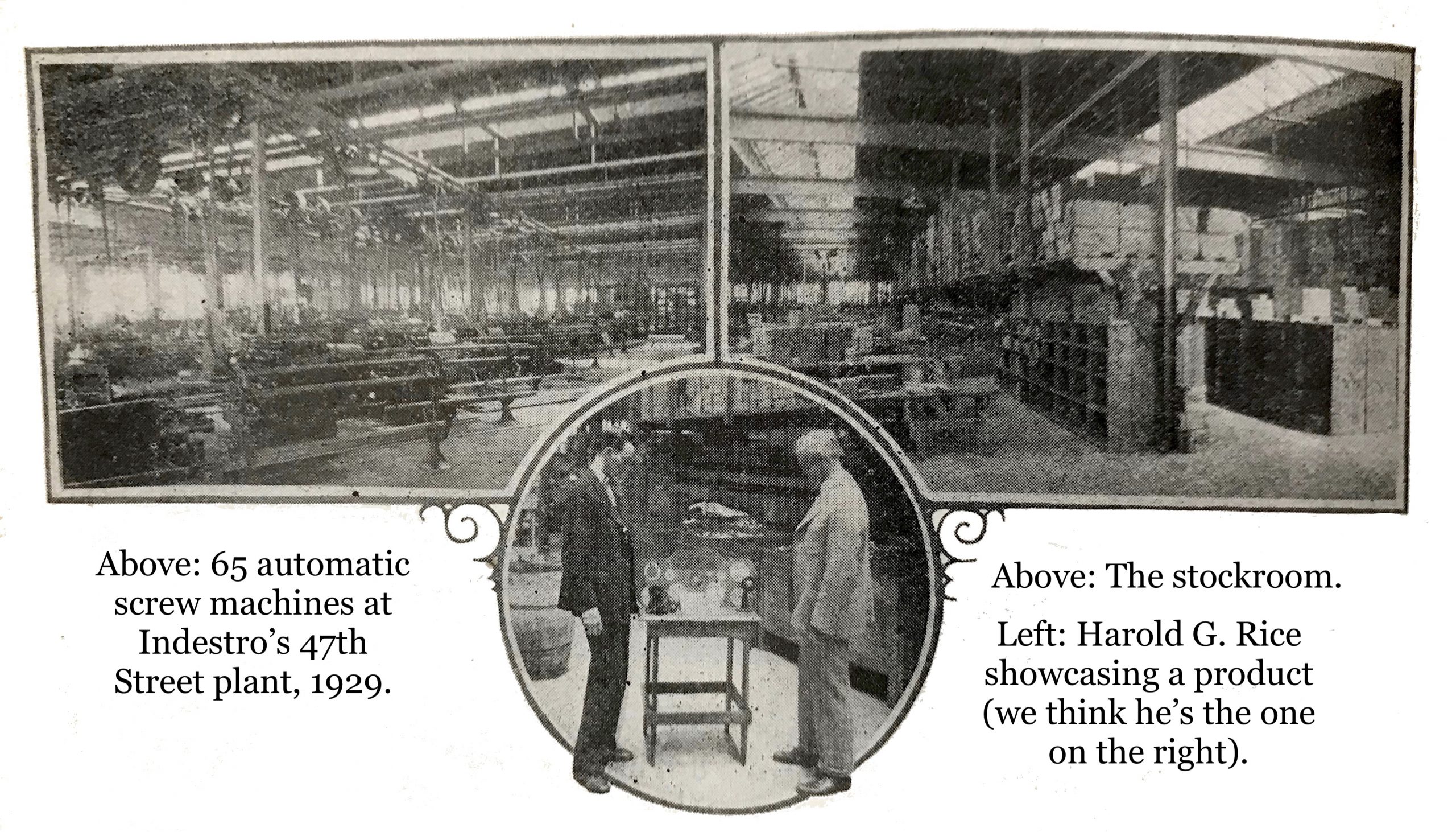

Right up until the stock market crash of 1929, Indestro was one of those hardware firms on a rocket-like upward trajectory. Earlier that same year, the business had settled into a major new 112,000 sq. ft. factory in the Central Manufacturing District (3429 W. 47th St.) and had grown to a workforce of 350, making not only bottle cappers, but a broad line of tools, automotive parts and novelties, from hammers and wrenches to can openers and Christmas tree holders. An Indestro ball peen hammer from this era is also part of our museum collection [click the photo above for more info].

Right up until the stock market crash of 1929, Indestro was one of those hardware firms on a rocket-like upward trajectory. Earlier that same year, the business had settled into a major new 112,000 sq. ft. factory in the Central Manufacturing District (3429 W. 47th St.) and had grown to a workforce of 350, making not only bottle cappers, but a broad line of tools, automotive parts and novelties, from hammers and wrenches to can openers and Christmas tree holders. An Indestro ball peen hammer from this era is also part of our museum collection [click the photo above for more info].

The new plant had arsenals of 65 punch presses and 65 automatic screw machines, along with additional departments for heat treating, finishing, drilling, tool & die, assembling, and shipping. Every worker could also enjoy an in-factory restaurant, modern heating and AC, and solid insurance plans.

“We are making more than 100 shipments a day,” H. G. Rice told the Central Manufacturing District Magazine in June of 1929, “with greater speed and less expense than previously.”

Rice bragged about updating his classic Indestro bottle capper with colorful new finishes, and touted how his business had poured its ample resources into more than 200 products, with 6 million pounds of steel put into use annually. “With us, one thing leads to another,” he said. “Constant research to improve our merchandise reveals, almost incidentally, new ways of utilizing our machinery and new items to produce. In that matter, largely, the expansion accounts for itself.”

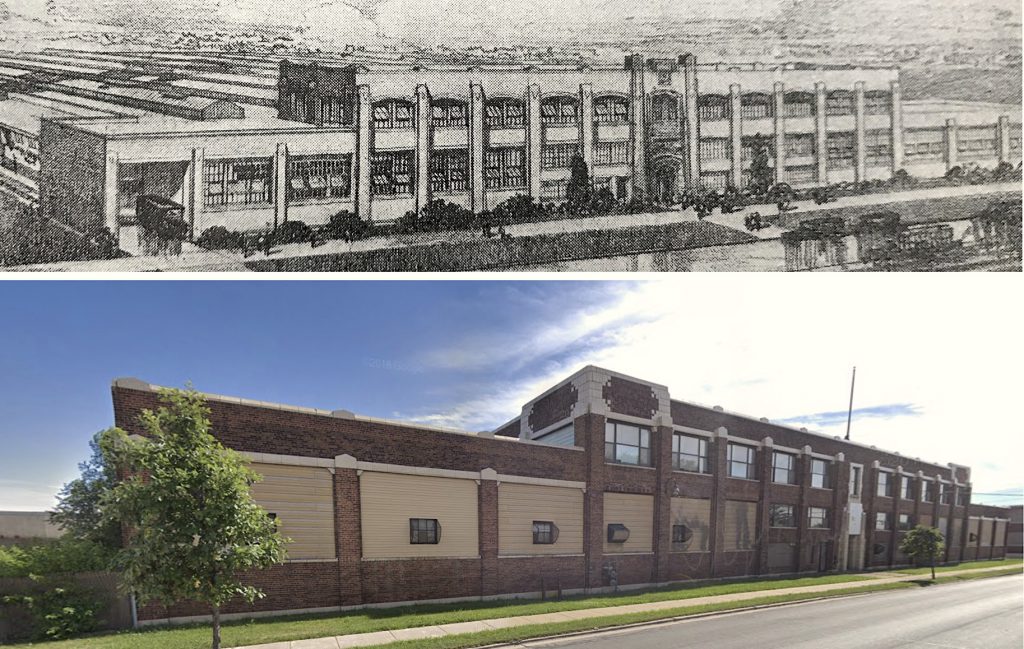

For a brief moment, Indestro was a shining example of a well-run business that had grown 100-fold in less than a decade. Just four years later, that same factory was liquidated, and Harold Rice was on his way back to Oregon. Indestro had stretched itself thin, and the Great Depression had crushed it into dust. Of course, that doesn’t quite put the proverbial cap on our tale.

[Indestro’s last factory as an independent, at 3429 W. 47th Street, is still standing, and was most recently home to a Powell’s Books wholesale warehouse.]

[Indestro’s last factory as an independent, at 3429 W. 47th Street, is still standing, and was most recently home to a Powell’s Books wholesale warehouse.]

II. Duro Metal Products Co.

In the mid 1930s, the Indestro name and many of its familiar products began re-appearing, this time in affiliation with our friends over at the Duro Metal Products Company. From the looks of it, while Harold Rice and countless other toolmakers were marching to their doom in the pre-crash bubble, Duro Metal had managed to armor itself against the blowback, largely by complementing its high-end Duro-Chrome hand tools with new offerings they liked to call “Tools of Progress,” i.e. modern power tools and machines that were a good deal more sophisticated than crank-operated bottle cappers. They also maintained deals with mail order houses like Sears and Montgomery Ward, keeping them in both the home/budget and high-end/trade segments of the industry.

As such, company owners Norris McNaught and William Odlum (along with their current / future wife Gertrude) were in a secure enough position to take over the remnants of Indestro and several other unfortunate victims of the Depression.

As such, company owners Norris McNaught and William Odlum (along with their current / future wife Gertrude) were in a secure enough position to take over the remnants of Indestro and several other unfortunate victims of the Depression.

“Throughout the days of the ’20s, as well as the more strenuous years that followed,” a company catalog boasted in 1935, “DURO has maintained an even keel, with but one thought in mind—PROGRESS!”

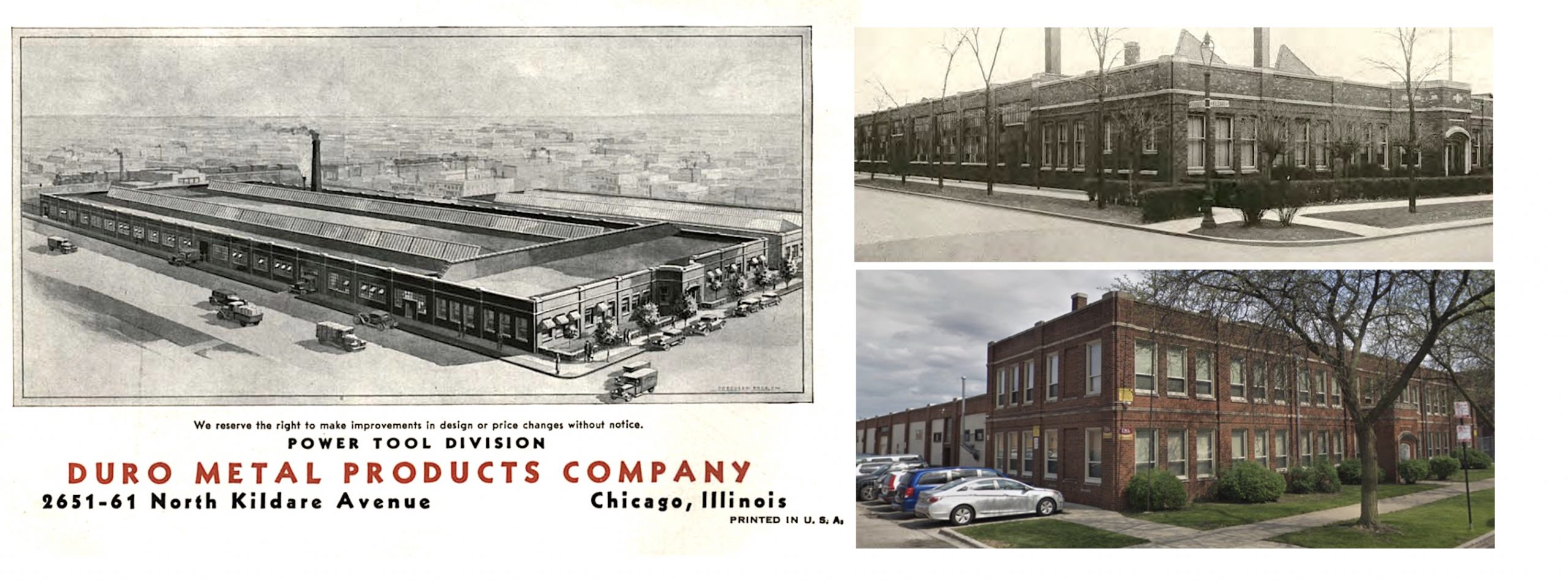

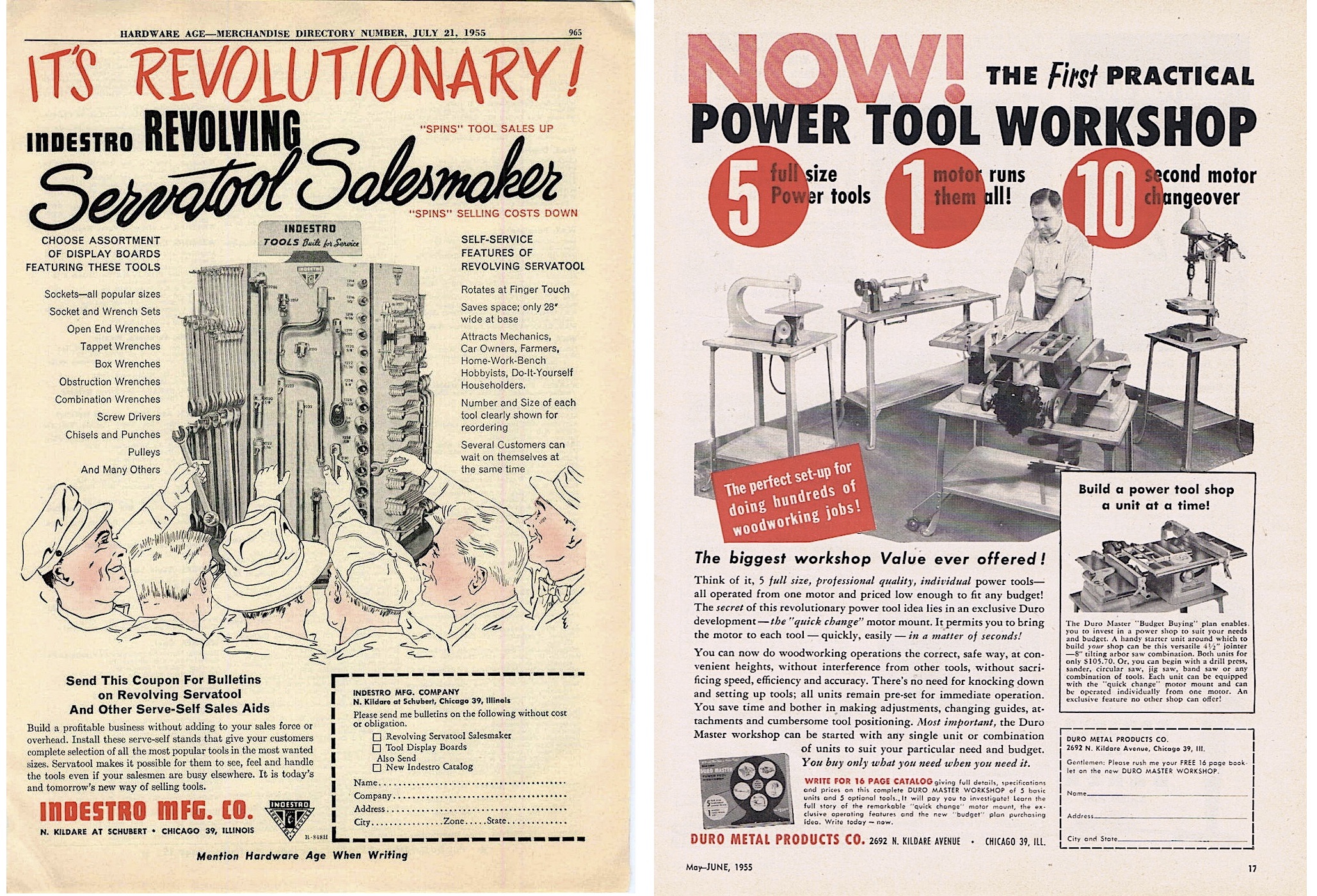

From 1923 to 1990, Duro Metal was based out of the same headquarters at 2649 N. Kildare Avenue in Hermosa. So naturally, when McNaught and Odlum re-organized Rice’s old business as the “Indestro MFG Corporation,” it was listed under that same address. Indestro had become, by any fair assessment, a subsidiary of Duro Metal, but it wasn’t exactly a clearly defined relationship in the public sphere. In fact, McNaught and Odlum treated their Indestro division as a virtual equal to the Duro line. While the latter created the “Tools of Progress” (inspired by the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair and its “Century of Progress”), Indestro was given a slogan of its own: “Tools for Service.”

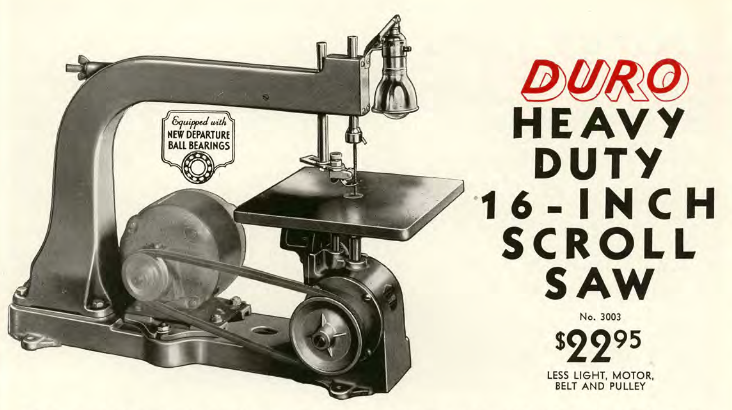

The two entities maintained their own separate catalogs for decades, with Duro offering an expanding line of automotive, power tools, and industrial machine tools (band saws, drill presses, lathes, etc.), and Indestro specializing more in quality handyman classics: sockets, wrenches, ratchets, etc. Still, the lines were often blurring, as the R&D department at the Kildare plant, it seemed, might arbitrarily push one product down the Duro hatch and another comparable item down the Indestro hatch.

“We do not claim to make all the good machinery,” read the Duro catalog of 1935, “but we do state that whatever we do make is the best that can be purchased at that price. . . . We have all the necessary facilities–Executive ability, and experience; Modern plant and equipment; Buying power and Mass production. Plus the fact we are an entirely self-contained organization that is not forced to pay a second profit on a great many parts as others do because of a lack of facilities or a limited production.”

[The Duro Metal / Indestro Factory No. 1 at 2649 N. Kildare Avenue, as seen in the 1930s and today; a second story was added to the front of the building some time in between. It’s still in use as a multi-purpose warehouse and recording studio. At its height, Duro also operated two other facilities in the city.]

[The Duro Metal / Indestro Factory No. 1 at 2649 N. Kildare Avenue, as seen in the 1930s and today; a second story was added to the front of the building some time in between. It’s still in use as a multi-purpose warehouse and recording studio. At its height, Duro also operated two other facilities in the city.]

[Duro Heavy Duty 16″ Scroll Saw from a 1930s catalog]

In the 1940s, as all production shifted to government contracting, there was also a slight shift in power within the company. Norris McNaught’s death in 1942 increased William Odlum’s responsibilities as president, as well as his reliance on McNaught’s grieving wife, who also happened to be Duro Metal’s secretary/treasurer.

At the time, some advisors discouraged Gertrude McNaught, who was now 47, from keeping an active role in the company. And almost everyone told her to sell the sprawling farm in Schaumburg that she’d purchased with her husband just a few years before his death. To her credit, she ignored the naysayers, and instead helped lead Duro into its post-war heyday, while also developing her farmland into the nationally renowned “Rolling Acres” dairy estate, home to a dynasty of champion guernsey cattle.

“I had never seen a cow in my life, had never visited a farm when we bought the place,” Gertrude admitted to the Tribune in 1958. “I was a city girl. Isn’t that terrible? If I had my life to live over, I’d be a farmer.”

“I had never seen a cow in my life, had never visited a farm when we bought the place,” Gertrude admitted to the Tribune in 1958. “I was a city girl. Isn’t that terrible? If I had my life to live over, I’d be a farmer.”

In essence, that’s kind of what Gertrude McNaught did in her later years: she lived her life anew. Sure, she was still an executive with Duro and a board member with four other Chicago businesses, but her heart was rerouted.

“Somehow I never get tired of winning,” she told reporters after taking top honors at the 1967 International Livestock Exposition. It was her fifth consecutive title, but her first as a newlywed. Twenty-five years after losing her first husband, she finally made an honest man out of the other co-founder of Duro Metal. William Odlum wasn’t just her business partner of 50 years, he also had his own 400-acre dairy farm just a few miles from Gertrude’s. So, to their rivals on the guernsey cow circuit, it was quite the unholy alliance.

After Odlum’s death in 1974, Gertrude was finally elevated to the Chairmanship of Duro Metal. She was 79 years old, and likely committing more of her time to her farms than the daily goings on at the Kildare factory, but her presence was always larger than life.

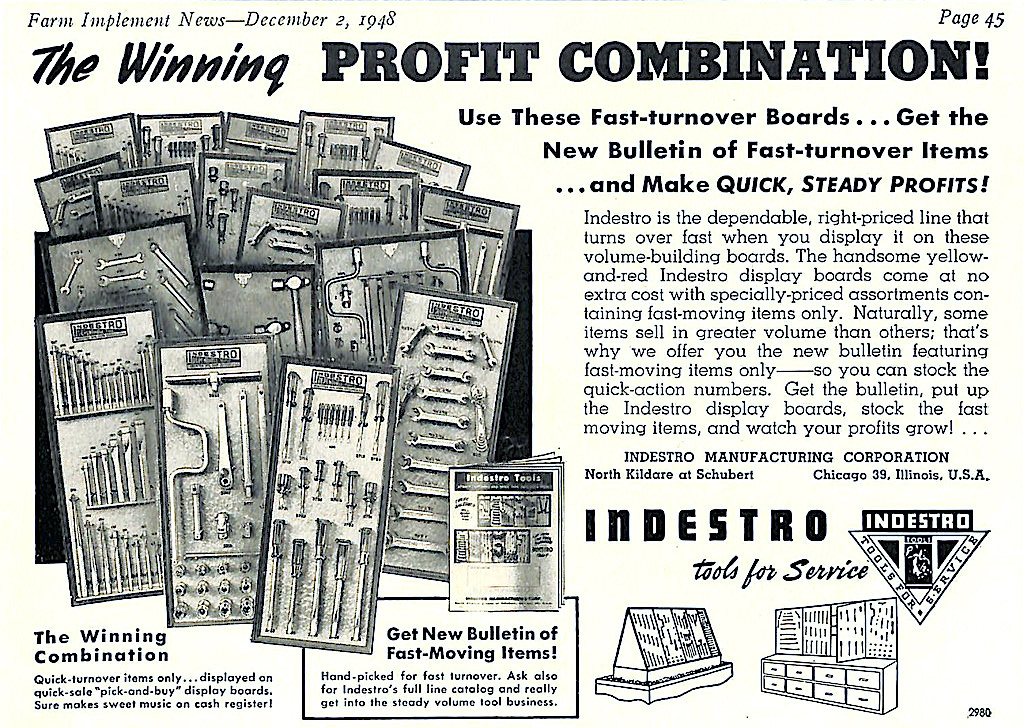

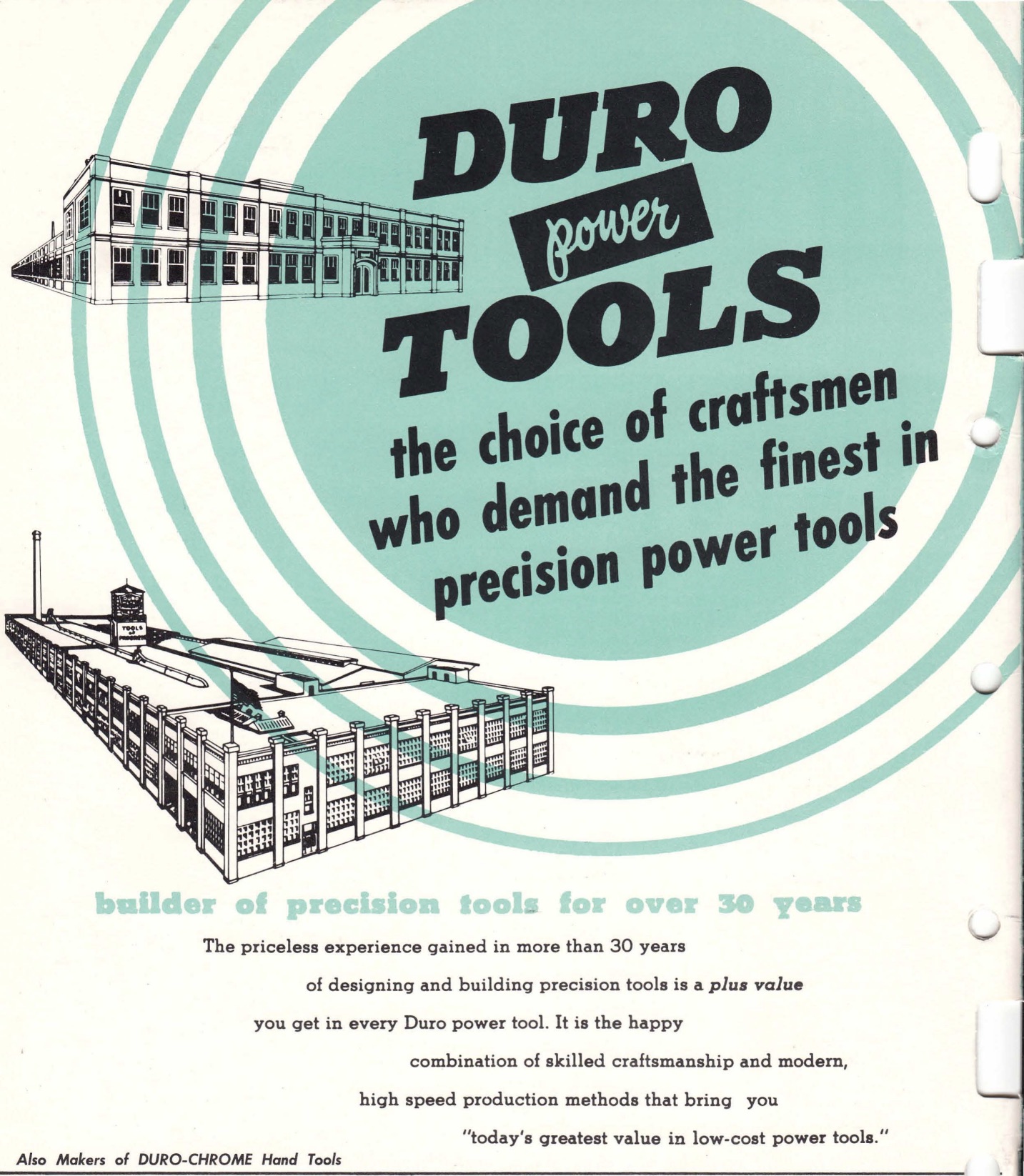

[1950s ads for Indestro and Duro Metal Products]

[1950s ads for Indestro and Duro Metal Products]

Unlike Harold Rice’s sudden financial collapse with Indestro in the early 1930s, Duro Metal’s eventual demise was a slow, 20 year wind-down from its heights as a tool titan of the mid-century. Despite the sterling reputation of the Duro-Indestro brand(s), cheap foreign competition was killing their marketshare, and a once state-of-the-art factory was now a relic from another time. Still serving as chairwoman in 1990, Gertrude McNaught Odlum, the widow of both company founders, agreed to dissolve the business after 73 years in Chicago. She passed away, as well, less than two years later.

Fortunately, many of the quality tools produced by Duro-Indestro are still in circulation—in some cases passed down across several generations, revered with a sort of wistfulness by the gearheads and handymen who wield them.

Sources:

“Duro and Indestro: The Tools of Progress” – AlloyArtifacts.com

“Study of a Successful Business Enterprise: Indestro Manufacturing Company” – Central Manufacturing District Magazine, June 1929

“Indestro All Steel Bottle Capper” – Hardware News, October, 1921

“A City Woman Is Right at Home on Farm” – Chicago Tribune, Sept 30, 1958

“Top Guernsey Breeder Wins with Relish” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 23, 1967

“Odlum Farm’s Gertrude M. Odlum, 96” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 23, 1992

“Large Plant for Central Factory Area” – Chicago Tribune, July 22, 1928

Duro Tools of Progress catalog, 1935

Bottle capper patent US1257637A

You guys with stripped ratchets might revive them by haunting swap meets, looking for rusty ones which are losing chrome plating.

If there is proper oil in the works, they might be good to swap innards.

Note that Indestro Select is bottom of the line, Indestro is middle, Super is tops.

Find out more about Duro at Alloy-Artifacts.com/

Without the cachet or collectability of Plomb, sockets may be had for one thin dollar

and I still see boxes for the sets with decal still inside.

Good idea about locating rusty or worn chrome Indestro ratchets to locate internal, replacement gears for good ones. Last year, 2023, I found at a flea market a nice, almost complete (missing one socket, replaced later) Indestro 1/2 drive, ratchet set with speeder and extensions AND the large red toolbox with the outside Indestro label and adhesive sticker inside listing all the sockets and additions for the complete set.

Back in 1967 while working at my first job at a True Value Hardware store, I bought my first tool set, an Indestro Super 1/2″ drive ratchet and socket set. Over the years, I added both straight and flex head Indestro Super 3/8″ ratchets. Today I still have and use the 1/2″-12 point socket set, and although I’ve kept the ratchets, regrettably the internal gears are stripped. I had hoped to repair them. In thier time, those tools were every bit as good as tools my Snap On tools. BTW, as I spent a lifetime working in the automotive trade, those tools were used everyday.

Since it’s unlikely that I will find replacement gears for the ratchets, I’d happily donate them to the Made in Chicago museum.

I meet Gertrude as a Associate Pastor at St Peters UCC in Chicago in the Golden fellowship group. I helped her sister by changing her tire in the winter. That next week Gertrude gave me a winderful gift of Duro tools and Indestro tools also which I still use to thus day 45 years later.

Her nephew also gave me a great grinder which I use every week. The whole family were wonderful and until I moved away s visited often and was able to visit her neice who was confinded to a Nursing Home as a pastor.

I worked in the Marketing department in the early 1980s producing catalogs and flyers for both product lines. Copies are still in my collection of past work. On one occasion while the plant was on strike, we in marketing were packing and shipping product to customers. Mrs. Odlum stopped by to see how we were getting along since she heard we had made paper pirate hats to wear while we worked. She got a real chuckle out of it.

I have a bottle caper paten is NOV 1921 It is in good condition I would like to sell it what is it worth hope someone can help.

I have a pair of fence pliers made by Indestro. They are of good quality and still work like new. Someone will likely still be using them 100 years from now.

I have 2 ratchets. one is a #4582 and #6272. I need the refills for them.

I’m glad to find the history behind the capper. I have recently obtained one of these great historical tools, and plan to continue using it.

I have 4 wooden bars tiles with a duro tag on all of them and can’t find nowhere on iternet also have a. Capper

My dad was the export manager for Duro/Indestro for many years. He took great pride in the products they made. I remember one country where they exported to was Iran. It is memorable because the son of dad’s customer came to the US and stayed with us for a while before heading out to Utah to attend BYU! He didn’t stay long, as he was a party boy, and oddly enough, the school didn’t meet his expectations 🙂 I visited Rolling Acres farm sometime in the 1960s and remember well the Guernsey cows. It seems to me that the farms were out near Rolling Meadows. We lived in Glenview, and it seemed like a real ride out into the country to get there.

There is a large collection of pictures of Duro tools here

http://vintagemachinery.org/mfgindex/detail.aspx?id=270&tab=4

I believe it was more the decision of the retailers like Montgomery Wards and Sears to stop selling large shop power tools in their stores which was much more responsible for the end of Duro. Duro was a large OEM for Montgomery Wards and after the war likely produced far more materials for sale in their network of stores than they sold for themselves. I do not think they had much in the way of retail outlets such as a large network of hardware stores. When Montgomery Wards dropped most of their larger hardware in the 80’s that likely spelled the end of Duro. Duro could have done what Craftsman and others did and outsourced to Japan but while Craftsman had Sears (and now Lowes and to a lesser extent Home Depot) Duro did not have that so what would have been the point.

I own a Duro floor standing drill press that was manufactured sometime in the 1940’s. A modern similar drill press would be the Delta Machinery model 18-900L and cost on that is $1,500 from Lowes. The runout on my Duro is not good but that’s because it’s old. I could have the quill rebuilt and the taper reground for around $500 and it would be good as new. So as you see brand new machines even with manufacturing outsourced to China or Japan are much more expensive than older machinery that is still around, in many cases.

I have a tool that may be called an adjustable face spanner from an Indestro 1/2” socket set.

It basically looks like an adjustable width, flat screwdriver for a 1/2 inch ratchet, but I’m not sure what its uses might’ve been because it’s basically made out of Sheet Metal. Where would engage whatever it’s turning.

DoesIt basically looks like an adjustable width flat screwdriver for a 1/2 inch ratchet, but I’m not sure what it’s uses might’ve been because it’s basically made out of Sheet Metal. Where would engage whatever it’s turning.

Does anyone know the specific use of this tool?