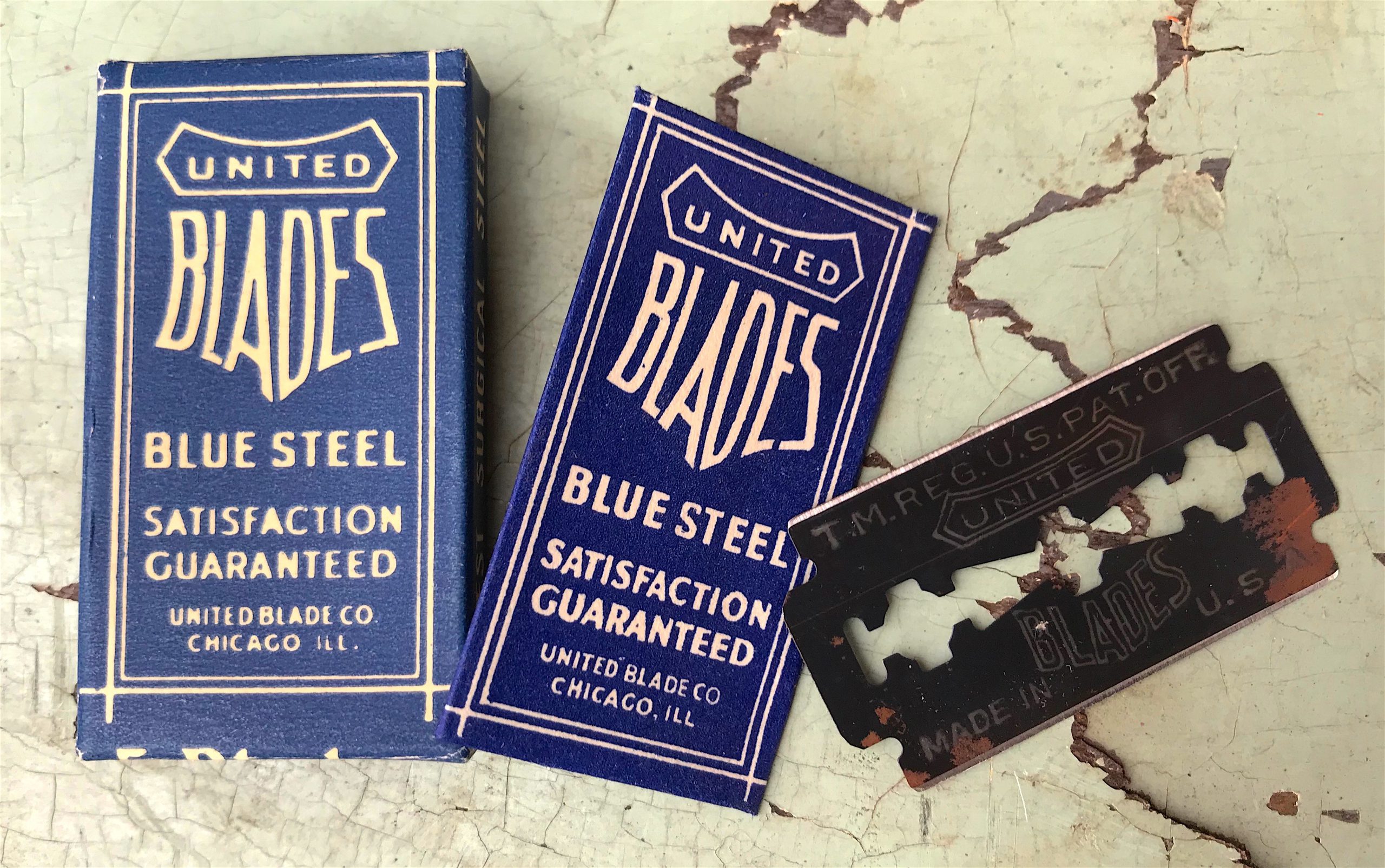

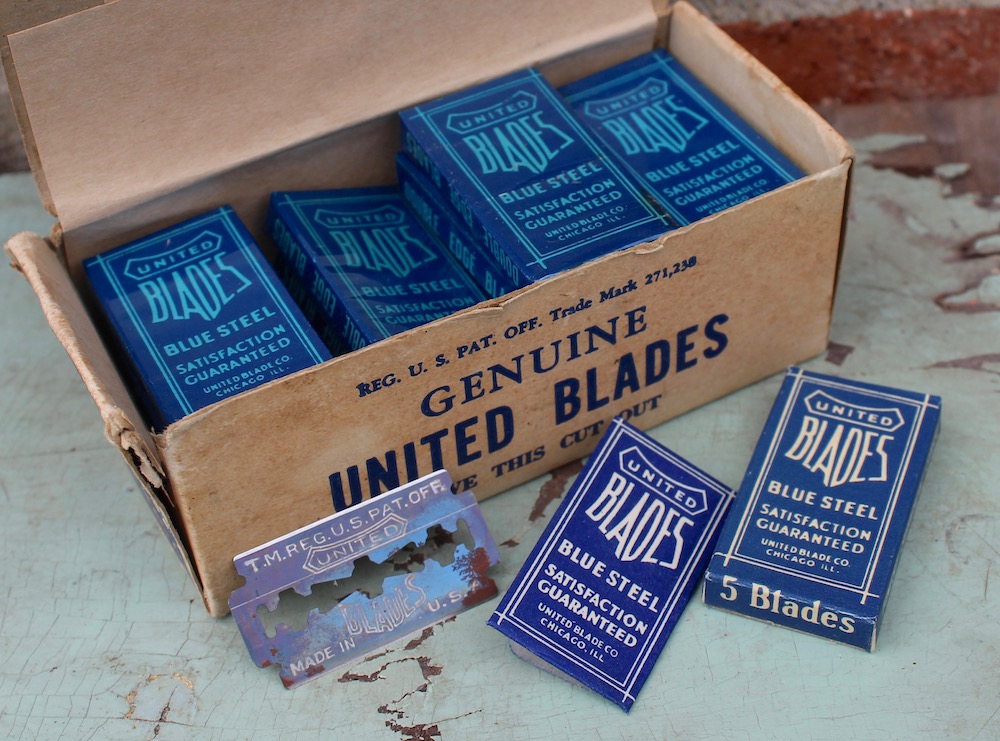

Museum Artifact: Box of Blue Steel United Blades, c. 1937

Made By: United Razor Blade Corporation / United Blade Co., 222 W. Adams Street, Chicago, IL [Downtown / The Loop]

Like the warm analog tone of a vinyl record, sometimes a bit of obsolete technology comes back around again and proves its worth to the modern age. The good old double-edge safety razor blade might be another such example, as many beard-weary men are now converting to the idea—after decades of escalating multi-blade hysteria—that the simpler shave stylings of the “Greatest Generation” might actually get the job done just as well, if not better.

Double-edge stamped steel blades, in their classic form, are still being produced today for a niche market by companies like Gillette, Astra, Feather, Derby, Shark, and others. For the true purists in the retro-minded whisker-trimming community, however, a perfectly preserved 100-count box of “Blue Steel” United Razor Blades—as procured for our museum collection—offers a more genuine peak into grandpa’s medicine cabinet.

Double-edge stamped steel blades, in their classic form, are still being produced today for a niche market by companies like Gillette, Astra, Feather, Derby, Shark, and others. For the true purists in the retro-minded whisker-trimming community, however, a perfectly preserved 100-count box of “Blue Steel” United Razor Blades—as procured for our museum collection—offers a more genuine peak into grandpa’s medicine cabinet.

* * *

The modern safety razor didn’t really come into mass use in the U.S. until the design refinements of the famous King C. Gillette around the dawning of the 20th century. Though his namesake multi-billion dollar business (now owned by Procter & Gamble) has always been a Massachusetts institution, Gillette himself was a Midwestern kid, born in Wisconsin and groomed as a salesman on the streets of Chicago. As an employee of the Crown Cork and Seal Co., he saw the success of new disposable bottle caps in the 1890s and hatched the idea of running the same racket in razor blades. Gillette launched his company in 1901 (by then having relocated to Boston), and 100+ years of disposable blade dominance was thus set into motion.

Today, Gillette has some increasing competition from old rivals like Schick as well as new online razor clubs, but the business model hasn’t changed too much. Importantly, each company makes sure that their respective razors aren’t interchangeable with any others—as all profits are really dependent on forcing customers to re-purchase those all-important brand-compatible blades. By contrast, back in the 1920s and ‘30s, things were a tad more loosey-goosey.

And that’s how we have a mysterious fly-by-night company like Chicago’s United Blade Co., aka the United Razor Blade Corporation.

For roughly 15 years—from the late ‘20s through the later years of World War II—various iterations of this business produced thousands (perhaps even millions) of single and double-edge razor blades, which they openly promoted for use with Gillette’s wildly popular safety razor. The United Blade Co. didn’t even make a safety razor of their own, and they certainly weren’t associated directly with Gillette in any corporate sense. Instead, they had to cross their fingers every year and hope that Gillette wouldn’t suddenly alter its mechanism and throw this whole lopsided relationship into irrelevance.

Might sound like an unstable business plan, but it had a pretty good shelf life all considering, as United Blade’s lone product—despite no discernible design modifications over the years—was just popular enough (and affordable enough) to survive the Great Depression. It didn’t hurt that the durable Swedish steel, aka “Blue Steel” blades (a big influence on the signature poses of male models for generations to come) were sold in an appropriately sleek midnight blue package with a distinctive, shield-shaped UNITED BLADES logo.

Based on newspaper ad circulation, it looks like the United Blade Co. mostly shipped its goods around the Midwest. They also likely outsourced the actual manufacture of their blades to an unknown Chicago steel mill, and operated primarily as a distributor. Any details beyond that, unfortunately, come almost exclusively from court documents—particularly a civil action brought to the Common Pleas Court of Summit County, Ohio, in 1935.

In that less-than-legendary case, the United Razor Blade Corp. of Chicago accused the Akron Drug Sundries Company of unlawfully using the “United Blades” trademark, and demanded $100,000 in damages. The Akron company—which felt it had rightfully purchased the rights to the name—fiercely refuted the plaintiff’s claim, and the resulting legal skirmish would carry on in both Ohio and Illinois over the next two years. In retrospect, the whole thing has an air of Depression-era desperation to it. But the court documents it produced have at least left us with a rough sketch of the United Blade Company’s key players and early history. It also shows the strange legal loopholes people will often jump through to keep a dream afloat.

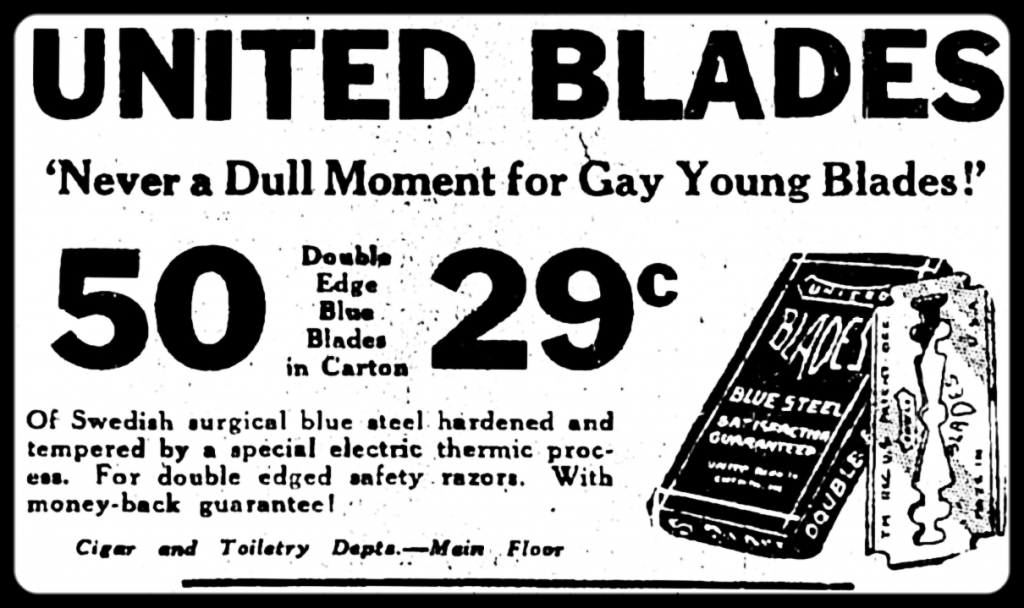

[A newspaper ad for the Goldblatt department store in Hammond, Indiana, included this promotion for United Blades on October 1, 1937. “Never a Dull Moment for Gay Young Blades!”]

[A newspaper ad for the Goldblatt department store in Hammond, Indiana, included this promotion for United Blades on October 1, 1937. “Never a Dull Moment for Gay Young Blades!”]

A Loose Timeline of the United Blade Company

1928-1930 – The business is started by a Czech immigrant and Hyde Park resident named Louis Schwarz, an experienced salesman who is also employed as the vice president of a linen imports company. Schwarz is already about 50 years old, and any details about how or why he decided to break into the razor blade game are aggressively absent. We only know that he trademarks the United Blade name for the first time in 1930, and works with an unknown manufacturer to produce them.

[One of the earliest newspaper ads mentioning United Blades, paid for by the E.E. Jandrey Co. in Appleton, Wisconsin, in October of 1930, notes that the blades were “made by a favorably known manufacturer, whose name we cannot use.” Unfortunately, that manufacturer remains a bit of a mystery today]

[One of the earliest newspaper ads mentioning United Blades, paid for by the E.E. Jandrey Co. in Appleton, Wisconsin, in October of 1930, notes that the blades were “made by a favorably known manufacturer, whose name we cannot use.” Unfortunately, that manufacturer remains a bit of a mystery today]

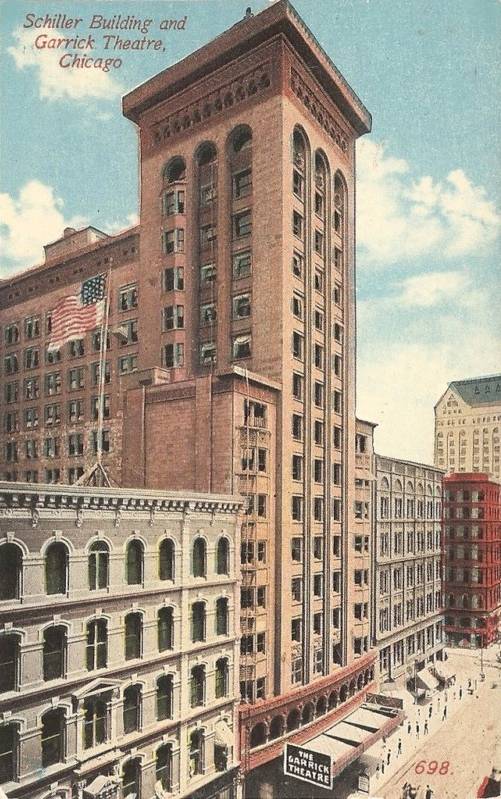

1931 – Schwarz’s business is officially incorporated as the United Razor Blade Corporation, with an office in the old Schiller Building, 64 W. Randolph Street, room 504. As an interesting twist, Louis’s wife Katherine Schwarz (also Czech and of about the same age) is identified as the majority stock owner, and subsequently is named president of the company, even though Louis is still alive and presumably in control of his faculties. As to whether this is done because Katherine is actively involved in selling razor blades, or merely as some sort of legal strategy, is also unclear. It certainly becomes an important factor in the years ahead, though.

1933 – According to Katherine Schwarz’s later claims, the original trademark rights for the “United Blades” name and logo are transferred from the corporation’s control into her own sole possession. No clear paperwork ever emerges to prove this, but if it was done, it was likely to protect the trademark in the event that the United Razor Blade Corp. went out of business.

1933 – According to Katherine Schwarz’s later claims, the original trademark rights for the “United Blades” name and logo are transferred from the corporation’s control into her own sole possession. No clear paperwork ever emerges to prove this, but if it was done, it was likely to protect the trademark in the event that the United Razor Blade Corp. went out of business.

1934 – Sure enough, the United Razor Blade Corp. is dissolved as a result of failing to pay its annual franchise tax to the state of Illinois. #DepressionProblems

Things easily could have ended there, but instead, they start to get increasingly nutty. With their original company kaput, Katherine Schwarz and her two daughters organize a new business to sell their stockpiles of United Blades as well as a range of wholesale pharmaceuticals. They call it the “Louis Schwarz Corporation,” even though Louis Schwarz himself—who is still alive and still married to Katherine—owns zero stock in the new business. I’m sure there is a strategy at work here, and I encourage any lawyers to chime in and explain what Lou and Kat might have been up to.

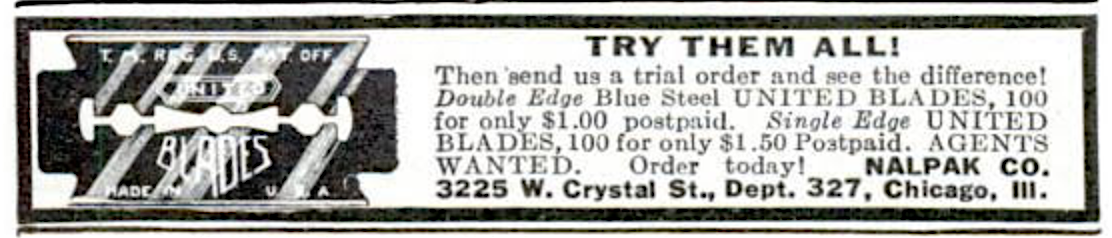

1935 – The new Louis Schwarz Corp., based at 508 S. Dearborn Street, is already hitting big problems of its own, with major debts lining up to its creditors. To survive, they strike up deals with more third-party distributors to peddle United Blades. Thus, we have obscure novelty businesses like Chicago’s Nalpak Company (better known for its line of whoopee cushions) advertising United Blades direct to consumers in 1935 and 1936.

[The Nalpak Company offers its own deal on United Blades above, not to be outdone by its “Poo-Poo Pillow” below. 1936.]

[The Nalpak Company offers its own deal on United Blades above, not to be outdone by its “Poo-Poo Pillow” below. 1936.]

One of the Schwarz Corp’s biggest creditors, incidentally, is the Akron Drug and Sundries Company. And in May of 1935, having failed at all other attempts to level her debts to the Akronites, Katherine Schwarz agrees to sell the major remaining assets of the Louis Schwarz Corp. to them, including—importantly—200 cartons of old United Blades. The Chicago business is now basically an empty shell . . . again.

According to court documents, “After the assignment by Louis Schwarz Corporation for the benefit of its creditors, the defendant Maurice Gussman, who is a stockholder and the secretary of The Akron Drug Sundries Company, went to Chicago and negotiated with the plaintiff, Katherine Schwarz, her husband and daughters, for the purpose of making some arrangement whereby the trade-mark might be used by a new corporation to be formed by Mrs. Schwarz and Gussman, whereby a certain part of the profits arising from the sale of razor blades would be applied toward the payment of the obligation owing by Louis Schwarz Corporation to The Akron Drug Sundries Company. These negotiations failed because Katherine Schwarz refused to associate herself with Gussman under any arrangement of the nature outlined.”

Call it courage or irrational stubbornness, but even with her back against the wall, Kat Schwarz isn’t interested in selling out or giving up the dream. Instead, with their second razor business now sunk into the swamp, the Schwarzes immediately set to work organizing yet another company—this time, a new version of the United Razor Blade Corp. “Third time’s the charm!”

Meanwhile, with his peace offering rebuffed, an annoyed Maurice Gussman goes back to Akron and takes a more aggressive approach, applying for the U.S. trademark on “United Blades,” which he believes is now legally up for grabs after the dissolution of both the original United Razor Blade Corp and Louis Schwarz Corp. The Patent Office agrees, and begins to review the application for approval.

Meanwhile, with his peace offering rebuffed, an annoyed Maurice Gussman goes back to Akron and takes a more aggressive approach, applying for the U.S. trademark on “United Blades,” which he believes is now legally up for grabs after the dissolution of both the original United Razor Blade Corp and Louis Schwarz Corp. The Patent Office agrees, and begins to review the application for approval.

When Katherine Schwarz catches wind of this, however, she files an objection, citing the earlier 1933 move that had supposedly placed the trademark under her own personal control, rather than that of the now defunct corporation(s).

The Patent Office takes a lenient stance on that one, and eventually allows Katherine’s lawyer to fine-tune some legal language and establish Katherine Schwarz as the rightful owner of the United Blades name, once and for all, but NOT retroactive to earlier dates.

Consequently, things don’t go as smoothly when Katherine then tries suing good old Mr. Gussman and the Akron Drug & Sundries Co. which had been selling the very United Blades that Katherine Schwarz handed over to them in the Louis Schwarz Corp. buyout. (Confused yet?)

In December of 1935, the Ohio court rules against Schwarz, essentially determining that, “It would be inequitable and unfair to permit plaintiffs to prevail in this lawsuit by the issuing of an injunction against the defendant, The Akron Drug Sundries Company, which purchased the business and assets, including the good will, of Louis Schwarz Corporation. The record does not disclose any evidence warranting the granting of relief to plaintiffs, or either of them, as against any of the defendants.”

[“State Street Day” promotion for United Blades by the Boston Store, Oct 21, 1932]

[“State Street Day” promotion for United Blades by the Boston Store, Oct 21, 1932]

1936 – Roughly one year after that first verdict, the U.S. Commissioner of Patents basically upholds the ruling, noting that the first supposed transfer of the United Blades trademark to Katherine Schwarz back in 1933 was “null and void.”

“Clearly Katherine Schwarz is estopped by that judgment to further litigate the question,” the judge adds, “and in my opinion the party United Razor Blade Corporation is equally estopped.”

The Schwarzes have lost the battle, keeping them on tenuous financial ground. But they have at least managed to retain their brand name, and so the United Razor Blade Corporation, Version 2.0, carries on.

1939 – In the Certified List of Domestic and Foreign Corporations for the state of Illinois in 1939, the United Razor Blade Corp. is now listed at 222 W. Adams Street, with Katherine Schwarz as president, Ethel L. Schwarz as secretary, and Louis Schwarz as the “registered agent of the corporation.”

1939 – In the Certified List of Domestic and Foreign Corporations for the state of Illinois in 1939, the United Razor Blade Corp. is now listed at 222 W. Adams Street, with Katherine Schwarz as president, Ethel L. Schwarz as secretary, and Louis Schwarz as the “registered agent of the corporation.”

1940 – The census shows Louis and Katherine living together, renting an apartment with Ethel at 5200 S. Blackstone Avenue, still in Hyde Park. Louis is listed as a salesman for a “steel products” business, while Ethel is a secretary for the same business. Interestingly, Katherine Schwarz doesn’t have an occupation listed, even though corporate records still list her as United Razor’s president during this time. This suggests that Louis Schwarz might have been the more public face of the company on the sales front, while his wife might have been more of a figurehead. Or, since it was 1940, the woman might merely not have gotten her proper credit.

1942 – Louis Schwarz dies at the age of 65 while in New York.

1943 – United Razor Blade Corp has moved its office a wee bit to 176 W. Adams Street, Room 1239. A fella named M. W. Gould has taken over as registered agent of the corporation, but Katherine Schwarz and her daughter Ethel are still president and secretary.

1944 – Likely due to rationing during World War II, the production of United razor blades slows or ends entirely. All newspaper ads cease, and the business disappears from most lists of Illinois corporations.

1944 – Likely due to rationing during World War II, the production of United razor blades slows or ends entirely. All newspaper ads cease, and the business disappears from most lists of Illinois corporations.

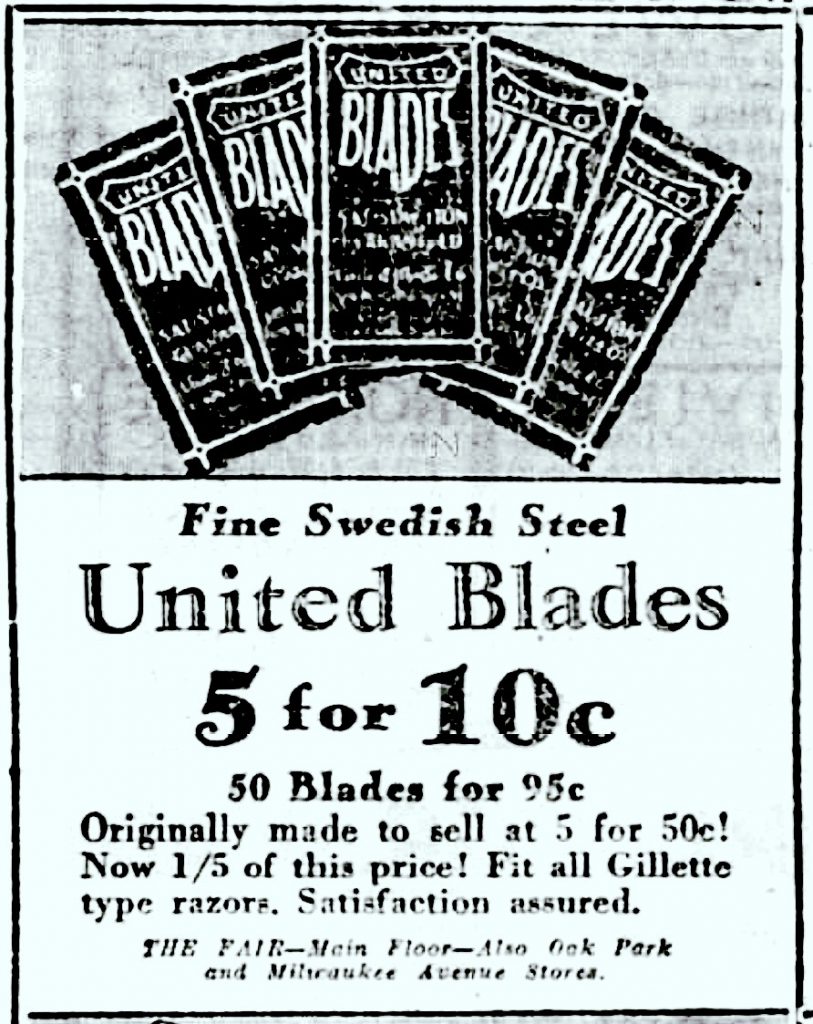

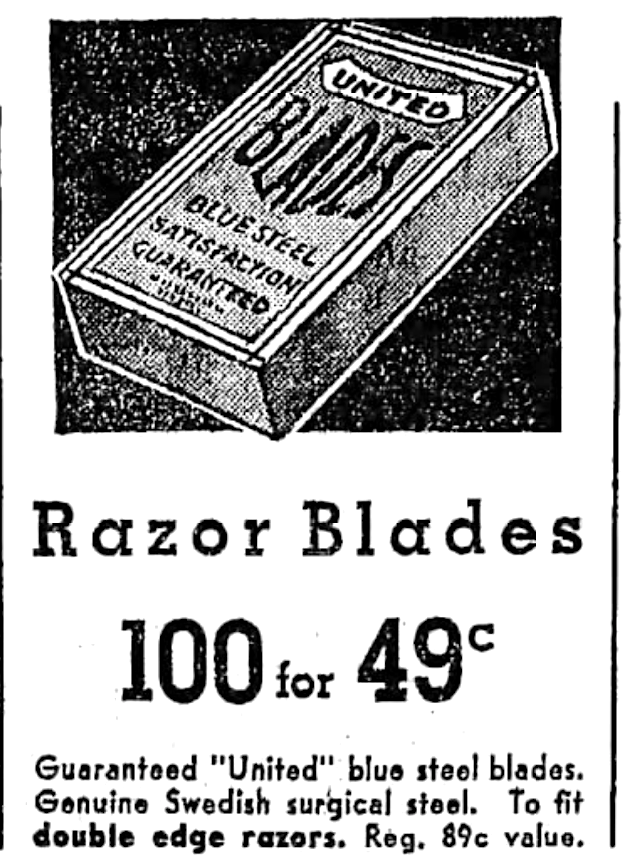

Back in 1930, you could generally buy a 10-pack of brand new United Blades for 50 cents (about $7.50 in today’s terms), meaning a set of 100 could set you back the equivalent of $75. By the time the second version of the United Razor Blade Corporation was in operation in the late ’30s and early ’40s, however, the blades’ market value had plummeted. In the 1938 newspaper ad show above, the same 100-count box from our museum collection was going for just 49 cents, or about $9 in modern terms. By 1944, some merchants were offering 25-count sets of United Blades for just 5 cents total. That means you could spend two dimes for 100 blades . . . seemingly endless shaves for less than $3 in modern-day money.

Complicated Depression economics certainly had a lot to do with that enormous drop in razor values, but even so, the business never had a chance of surviving when they were giving away their goods at the end. If only the Schwarz family had known that people would be willing to spend $15 to $20 on a meager 4-pack of quatro and cinco blades . . . the United Razor Blade Corp. might still be in business yet.

Sources:

“United Razor Blade Corp. v. Akron Drug Sundries Company,” 1936

Certified List of Domestic and Foreign Corporations, Illinois, Vol. 2, 1939

Certified List of Domestic and Foreign Corporations, Illinois, Vol. 2, 1943

Chicago Tribune, October 21, 1932

Chicago Tribune, June 24, 1932

Chicago Tribune, April 3, 1938

Chicago Tribune, Jan 10, 1943

The Dispatch (Moline, IL), April 16, 1943

The Times (Hammond, Indiana), October 1, 1937

The Post-Crescent (Appleton, WI), October 15, 1930

Archived Reader Comments:

“Thanks for a very informative article. I am a traditional “wet-shaver”, meaning that I use double-edge razors (albeit with modern stainless steel blades), shave soap or cream, and a shaving brush. I can today buy 100 blades for around $10…not much different when adjusted for inflation, as when compared to the United Blade 100 pack in 1938.” —Robert M. Kain, III, 2019