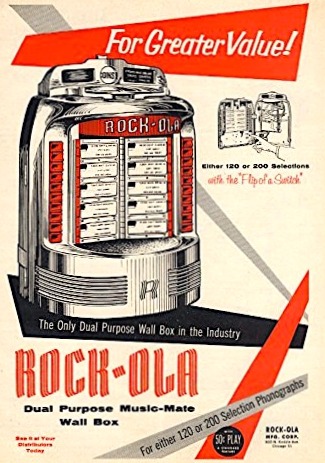

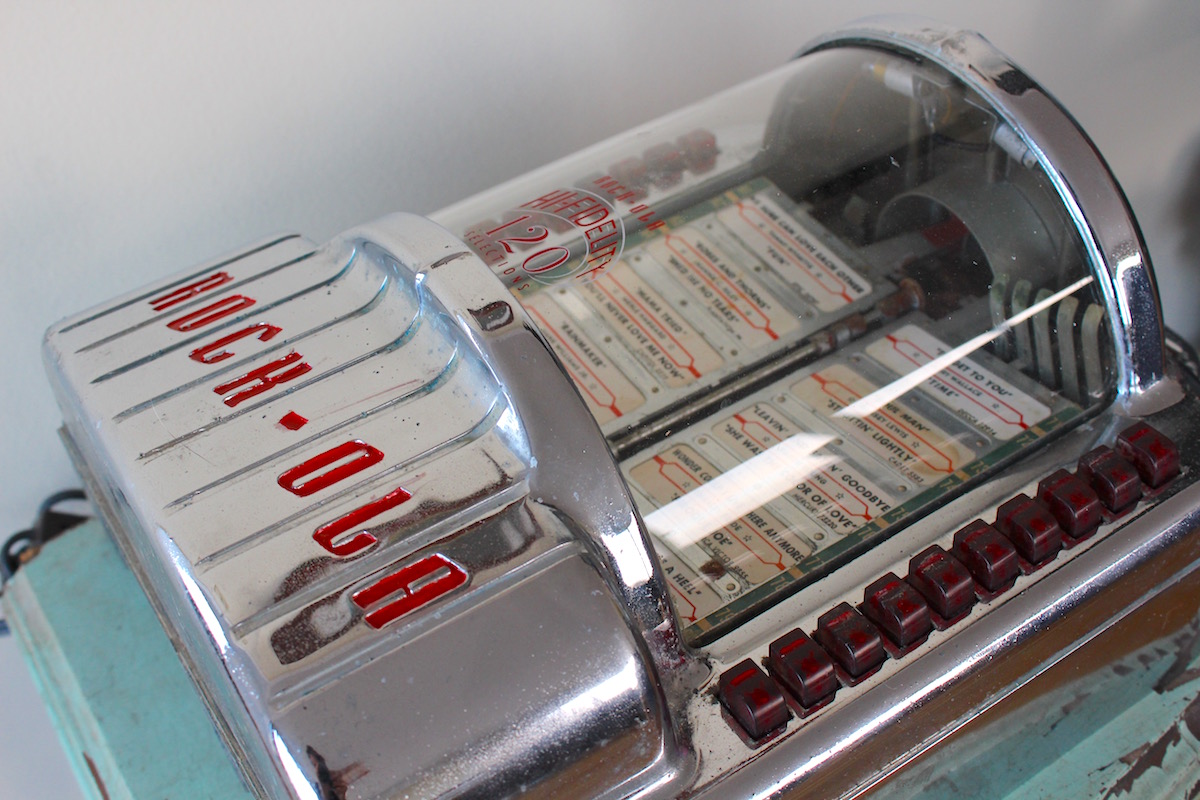

Museum Artifact: Rock-Ola Hi-Fidelity 120 Wall Box, 1953

Made By: Rock-Ola Manufacturing Corp., 800 North Kedzie Avenue, Chicago, IL [Humboldt Park]

It’s one of the quintessential brand names of American pop culture. Rock-Ola—a word that celebrates and encapsulates both the rock n’ roll explosion of the jukebox’s 1950s golden age and the historic roots of the classic “Victrola” talking machines. . . . or so one might presume, anyway.

In truth—and forgive me here as I blow your mind—Rock-Ola (trademark, 1935) was merely the hyphenated, real-life surname of the company’s founder and longtime president, David C. Rockola. His coin-operated sales and manufacturing business predated the rock revolution by decades, but Rockola himself—once known as the “crown prince” of Chicago’s mob-controlled slot-machine underworld—was a rebel from the start.

Before we get to the man, though, let’s have a look at the artifact.

Before we get to the man, though, let’s have a look at the artifact.

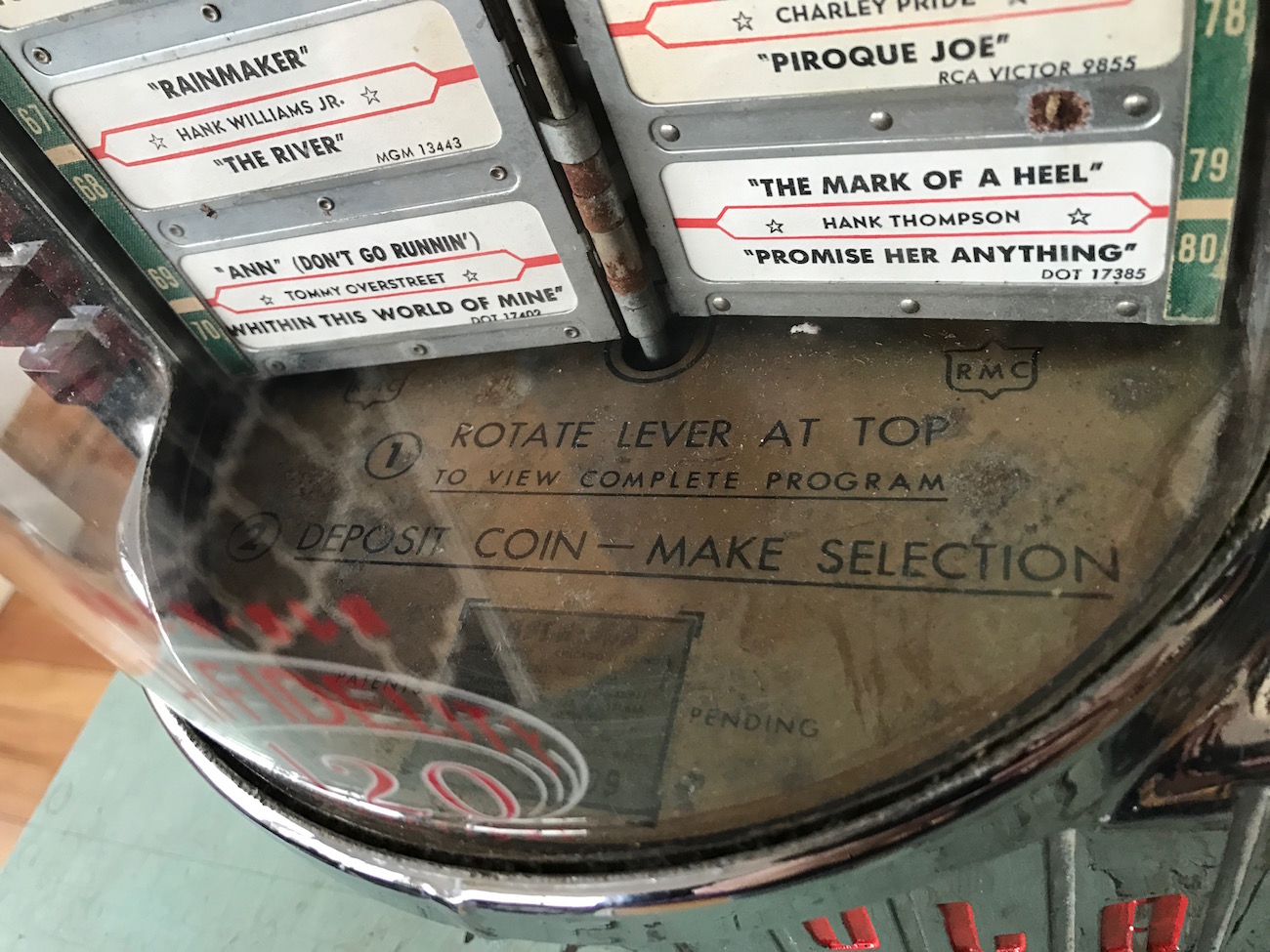

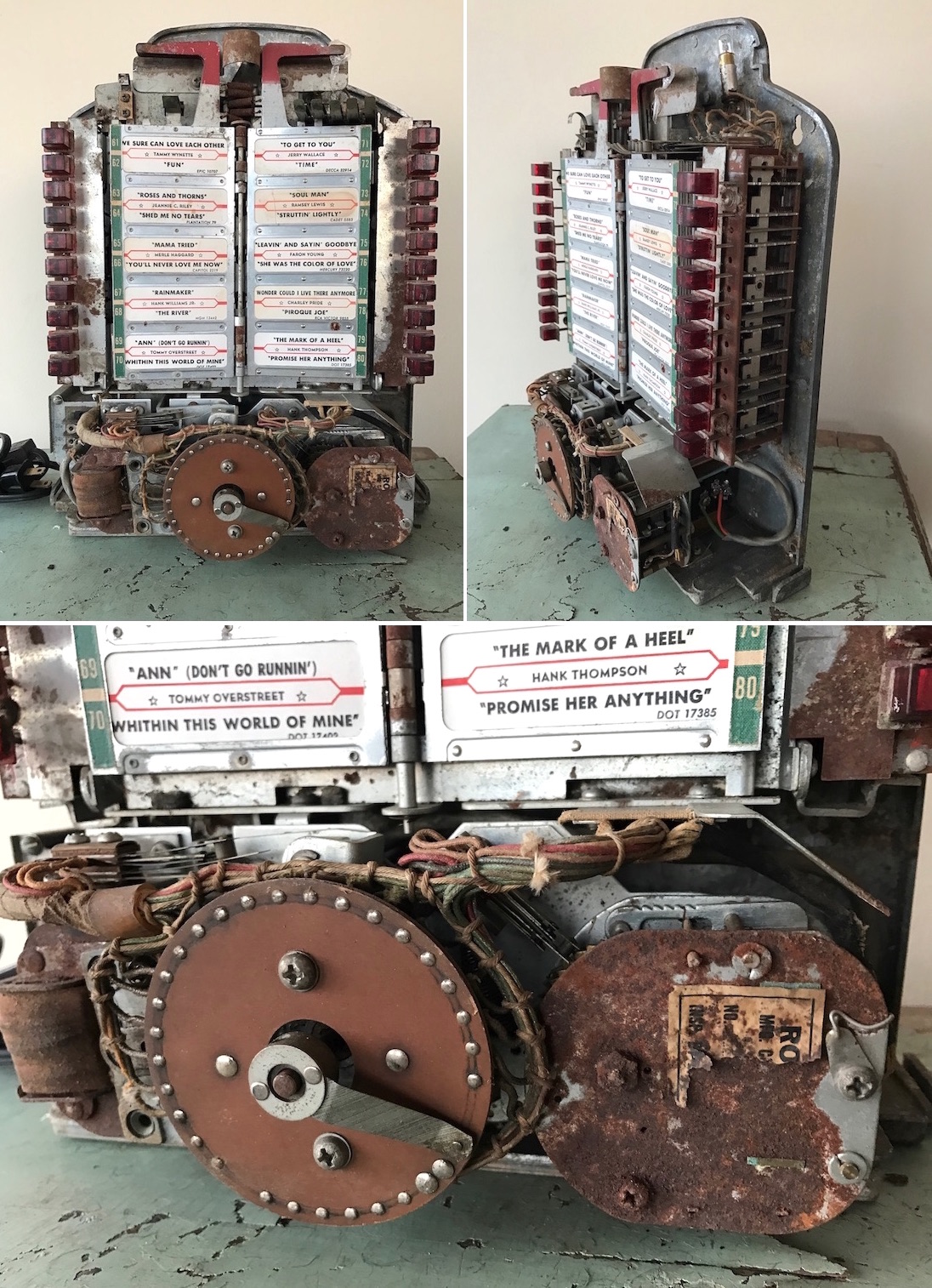

Produced between 1953 and 1957, the Model 1546 Rock-Ola “Comet” Wall Box in our collection was essentially the musical remote control of the greaser era. Rather than depending on your local Fonzie to punch in the right numbers on the gaudy five-foot jukebox in the corner, diner patrons could now flip through 120 song selections on a 14-inch, chrome-plated terminal right at their own table. Each wall box was connected to the establishment’s master jukebox, so whether you paid a dime for one tune or a quarter for five, the machine would slide its corresponding 7” vinyl singles into the proper sequence, creating a proto mixtape or iTunes playlist for the teeny boppers of the Eisenhower administration.

Judging by the song list still visible on our particular artifact, this wall box was retired some time in the early 1970s, just long enough to stock up on the latest hits from Tammy Wynette and Charley Pride. Aesthetically speaking, though, there is no separating a Rock-Ola jukebox like this one from the stainless steel bar stools, neon signs, and checkered terrazzo dance floors of 1950s America. In fact, many historians believe that the popularity of Rockola jukeboxes (one of the “big four” manufacturers of the period along with Wurlitzer, AMI/Rowe, and crosstown rival Seeburg) directly inspired Cleveland radio DJ Alan Freed to coin the term “rock n’ roll” in the early ‘50s. Another theory—of the more conspiratorial variety—claims that Freed picked up the phrase less through inspiration, and more through financial encouragement from Rockola himself. Either way, Rock-Ola and Rock n’ Roll were intrinsically and permanently linked from that point forward.

The connection to early rock music has helped keep the brand name alive among nostalgic collectors well into the modern day, as Rock-Ola jukeboxes are still being produced in Torrance, California, by the Antique Apparatus Co., which purchased the name and patents in 1992. Most of the focus is on re-creating the bubble-style, bright-colored, arched boxes of the ‘50s and ‘60s. The actual production era of the original Rock-Ola MFG Co. dates back long before than that, however. And those early days tell a tale every bit as sorted and dramatic as any rock anthem or country ballad you could pay a nickel to listen to.

The Man From Manitoba

David Colin Rockola (sometimes recorded as David “Cullen” Rockola) was born in Virden, Manitoba, Canada in 1897. Despite the Italian sounding musicality of the name, his father George was actually of Russian descent. George was also an amateur inventor, but it’s hard to say he inspired his son’s interest in machines. The fourth of five kids, David had already endured the divorce of his parents and the death of his mother by age 13, essentially ending his childhood ahead of schedule. Shortly thereafter, he left his home and school to try to make his way in the world. It was a journey into the Canadian wilderness—only instead of mountains and forests, David Rockola was moving from town to town, learning the merchant trade and growing unusually street smart and tough nosed for his age.

[David Rockola showing off some of his early coin-operated gum machines]

[David Rockola showing off some of his early coin-operated gum machines]

He was a bellhop in Saskatoon, then—while still a teenager—opened up his own cigar shop in another hotel in Medicine Hat, Alberta. He recounted the experience in a 1987 interview with a high school student named LeAnn Turbyfill—a cub reporter for her school paper in Kentland, Indiana.

“I went into the cigar business in this hotel and of course, like a fool, I worked all day and night,” Rockola said, hinting at an obsessive streak. “I ended up in the Medicine Hat hospital because I worked too many hours. I had diphtheria fever. They took my cigar store away from me.”

Undeterred, Rockola regrouped in Calgary, briefly running another cigar shop until the fates intervened to his benefit. According to one version of the tale (there are a few), two Australians came in the store one day and offered Rockola a ‘trade stimulator’, a type of coin-operated gumball machine that dispensed prizes—like vouchers for items in the shop. In short order, Rockola’s new machine was getting more business than his cigars, and more attention than the cute girl he’d hired to run the register. Barely 20 years old, he’d found his new life’s calling.

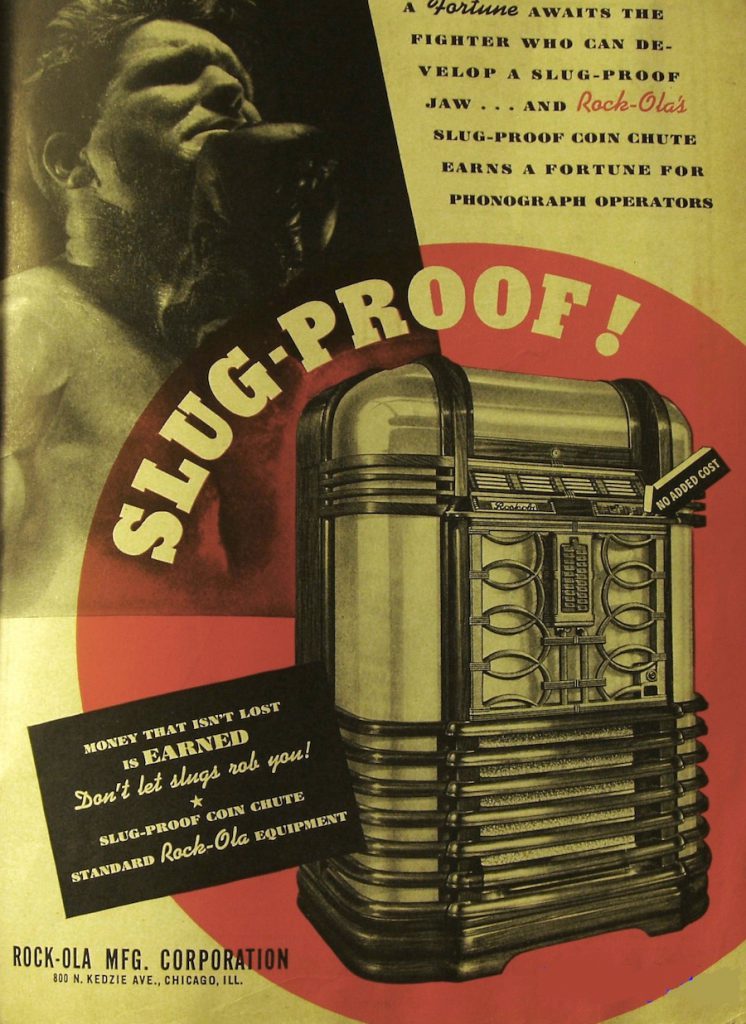

Coin-operated machines, while innocent novelties in many cases, had also generated a fair reputation for trouble by this point in time. For every well-meaning child’s game or weighing scale on the market, there were dozens of shady figures using similar slot gadgets to entice gamblers, rig outcomes, short-change the payouts, and skim off the untraceable profits to avoid taxes. Early on, the baby-faced Rockola seemed to be on the up-and-up with his mechanical interest in the devices. But he may have had his eyes on the bigger prizes down the road.

Chi-Town Bound

Crossing the border and arriving in Chicago in 1919, Rockola quickly took a job as an inspector with O.D. Jennings & Co. (a leading Chicago slot machine manufacturer), then worked for several years as a mechanic for W.E. Keeney and Sons—another local coin-op machine company. By the spring of 1927, a well seasoned 30 year-old Rockola was ready to fly the coup. He purchased roughly 200 slot machines from his cohorts at Keeney and the Watling Manufacturing Co., and set out to make his mark on the South Side.

It’s possible, I suppose, that Rockola was just a wide-eyed Canuck inventor with the purest of capitalist intentions. But considering how quickly he fell in with the city’s criminal element, it’s far more likely that he had his connections established well before going into business on his own.

In its infancy, the Rockola Scale Company operated predominantly as the secret supplier for an illegal “slot machine syndicate” doing business on the city’s South Side. It’s a detail that is often strategically skimmed over in company histories, but it’s a fascinating chapter that left major, lasting repercussions.

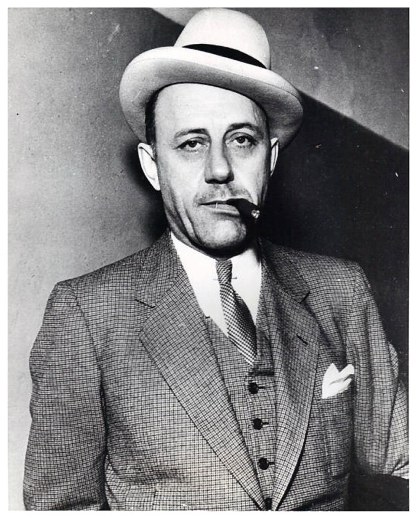

The main kingpins of the operation were three of the most powerful Irish gangsters of the period—the notorious bullet-dodger Edward “Spike” O’Donnell, [pictured], who survived at least a half-dozen attempts on his life, most by machine gun; Danny McFall, a former deputy-sheriff turned killer; and James “High Pockets” O’Brien, so named because, as a tall fellow, his pants pockets were up around most other people’s eyeballs.

The main kingpins of the operation were three of the most powerful Irish gangsters of the period—the notorious bullet-dodger Edward “Spike” O’Donnell, [pictured], who survived at least a half-dozen attempts on his life, most by machine gun; Danny McFall, a former deputy-sheriff turned killer; and James “High Pockets” O’Brien, so named because, as a tall fellow, his pants pockets were up around most other people’s eyeballs.

For the first year or so, the slot machine business flourished—largely because O’Brien had a lot of the South Side’s Irish cops, and even some key government officials, in his back pocket. These men routinely looked the other way as more and more of Rockola’s gambling machines began popping up in establishments large and small. As an important technicality, there were a few types of slot machines that were still legal to operate in the city at the time—particularly ones that gave out tokens or vouchers instead of cash (thus supposedly preventing the operators from short-changing players). With this in mind, the interpretation of the law was often bent and twisted—much as with the speakeasies of the same era— to the advantage of the men with the money and the fire power.

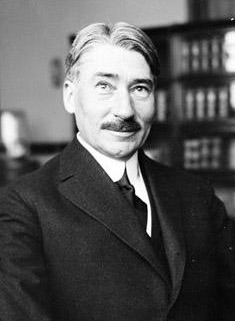

That began to change towards the end of 1928, when a former judge named John A. Swanson [pictured] took over as Cook County’s States Attorney. Though Swanson was a fellow Republican serving under the generally corrupt Republican mayor Big Bill Thompson, he made his reputation as an enemy of organized crime, and set forth on a new mission to break up some of the city’s mob controlled syndicates in 1929.

That began to change towards the end of 1928, when a former judge named John A. Swanson [pictured] took over as Cook County’s States Attorney. Though Swanson was a fellow Republican serving under the generally corrupt Republican mayor Big Bill Thompson, he made his reputation as an enemy of organized crime, and set forth on a new mission to break up some of the city’s mob controlled syndicates in 1929.

That summer, Swanson took on the rapidly growing slot machine racket, putting together the tangled web of wrong-doers and forming a grand jury to collect testimony. Among those who testified were David Rockola and his slot machine mentor William Keeney.

The Silent Snitch

Both Rockola and Keeney spilled the proverbial beans, implicating “High Pockets” O’Brien and acknowledging their own involvement in distributing illegal machines. Rockola even admitted to personally taking part in smuggling some confiscated machines out of police stations and paying off high-ranking officers.

“After May 1927, I entered into an agreement with reference to the operation of slot machines in Chicago,” Rockola told investigators. “I had a talk with James [High Pockets] O’Brien and he told me that if I wanted to pay him 75 percent of the receipts I could go ahead and buy some machines and install them in different districts, which he named at a later date, and for that 75 percent he would take care of the protection of the machines, see that the local police would not interfere and also the police downtown. . . . I was operating those machines practically all over the South Side.”

[Picture Below: David Rockola, left, entering court with his lawyer Louis Piquette, 1929]

Rockola’s full testimony was so thorough and so damning that Swanson essentially built the state’s entire case around it, rounding up more than 20 defendants for a series of criminal trials, including O’Brien, Spike O’Donnell, Danny McFall, a number of policemen, some politicians, and even one of Mayor Thompson’s righthand men, Dr. William H. Reid—whom Rockola had also singled out as a witnessed recipient of hush money.

Rockola’s full testimony was so thorough and so damning that Swanson essentially built the state’s entire case around it, rounding up more than 20 defendants for a series of criminal trials, including O’Brien, Spike O’Donnell, Danny McFall, a number of policemen, some politicians, and even one of Mayor Thompson’s righthand men, Dr. William H. Reid—whom Rockola had also singled out as a witnessed recipient of hush money.

When it came time to tell his story in court, however, Rockola—the man the media had dubbed the “Crown Prince of the Slot Machine Syndicate”—suddenly clammed up.

“David C. Rockola went to jail yesterday rather than tell the jury in the slot machine conspiracy trial the story on which the grand jury indicted the 21 defendants,” the Tribune reported on November 30, 1929. Even in a country still reeling from the stock market crash, this was front page news.

“Judge John P. McGoorty sentenced Rockola to six months in jail when he again refused to testify after he had been given complete immunity from prosecution, and could no longer fall back on his constitutional right to refuse on the ground that he might incriminate himself.”

In other words, Rockola tried to plead the fifth, but having been given immunity, this amounted to calling timeout in a basketball game when you don’t have any timeouts remaining.

Directly stating “I refuse to answer” any further questions, Rockola knowingly shattered the state’s hopes of getting any convictions, thus letting just about all the defendants in that case, and subsequent related cases, off the hook.

After finding Rockola in contempt of court, Judge McGoorty [pictured] read him the riot act. “You are largely the one who started the machinery of the law in motion on this case,” he said. “Now, by your contumacious attitude, you may render it impossible for the state’s attorney to proceed.”

After finding Rockola in contempt of court, Judge McGoorty [pictured] read him the riot act. “You are largely the one who started the machinery of the law in motion on this case,” he said. “Now, by your contumacious attitude, you may render it impossible for the state’s attorney to proceed.”

When Rockola’s lawyer, future John Dillinger attorney Louis Piquette, argued for bail to be set, the judge was stern in his refusal. “I do not wish to take any of his rights from this man,” McGoorty said, “but I will not release him until the Supreme Court compels me to. He has been guilty of a gross contempt in open court. Is the law so helpless and are the courts so impotent that such persons may not be properly punished? No, I will not, of my own volition, admit him to bail.”

And there it was. David Rockola, still just 32 years old, still a Canadian citizen, was sent to the Cook County slammer for six months. It might have seemed like a promising career was at an end. But all things considered, Rockola had actually made the smartest play for securing a long term future for his wife and kids in Chicago.

Maybe the widely published threats from Spike O’Donnell had spooked him a bit [“Wait’ll I get that guy Rockola on the cross-examination, I’ll give him plenty!” the mobster has supposedly boasted], but it was more likely that Rockola simply weighed his options like a street-smart fellow would. Ratting on the mob, the police, AND the mayor’s office would bring him far greater grief that a six month prison sentence for silence. More importantly, that act of sacrifice also ensured that his established business partners would still be there when he became a free man again. The slot machine industry he nearly brought down was, instead, saved by the testimony (or lack thereof) of David Rockola.

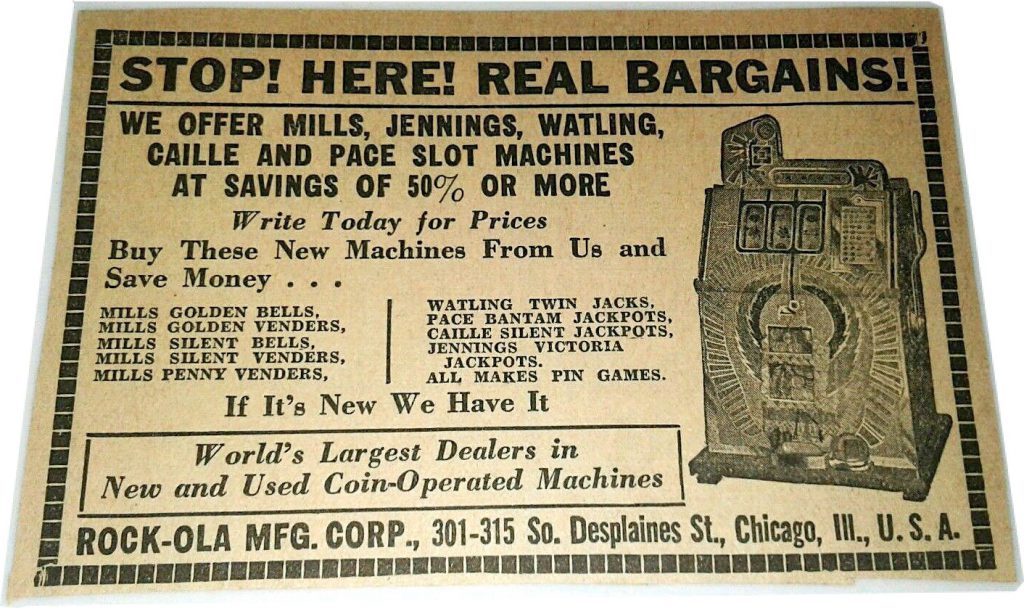

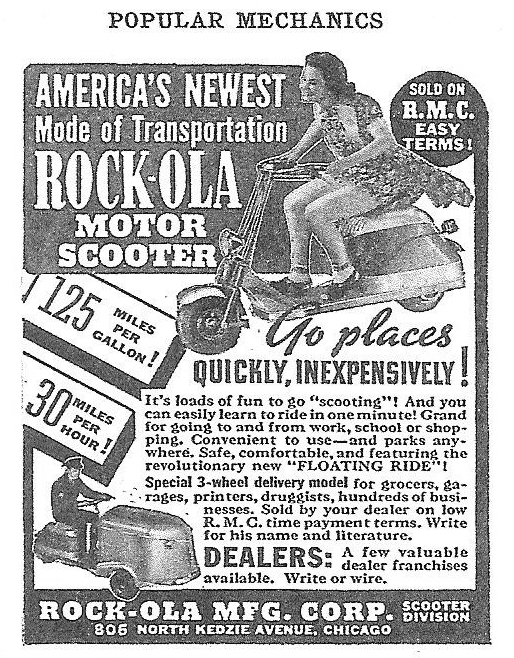

[A Rock-Ola newspaper ad from the early 1930s shows that the “crown prince of the slot machine syndicate” had no shame about setting right back to work after his jail sentence]

[A Rock-Ola newspaper ad from the early 1930s shows that the “crown prince of the slot machine syndicate” had no shame about setting right back to work after his jail sentence]

Back In Business

Sure enough, despite Swanson and other crime fighters’ attempts to hound the syndicate members in the years ahead, Rockola managed to get his record completely expunged and re-emerge as a major industrial figure, successfully swimming upstream out of debt during the Great Depression to become a revered, upstanding business owner.

Along with slot machines and scales, he became a major designer and manufacturer of coin operated games, including a couple innovative pinball games, starting with Juggle Ball (1932), followed by two entries for the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair—“Jig Saw” and “World Series Pinball.” The semi-legendary horse race trade stimulator known as “Sweepstakes” (where players pay a penny to gamble on mini horsies rotating on a turntable) was also produced starting in 1933. And did I mention the Rockola phonograph cabinets, bar cabinets, parking meters, gumball machines, and motor scooters? The business was versatile and prolific.

[Ads for two of Rock-Ola’s early pinball games, “Juggle Ball” and “Jigsaw”]

[Ads for two of Rock-Ola’s early pinball games, “Juggle Ball” and “Jigsaw”]

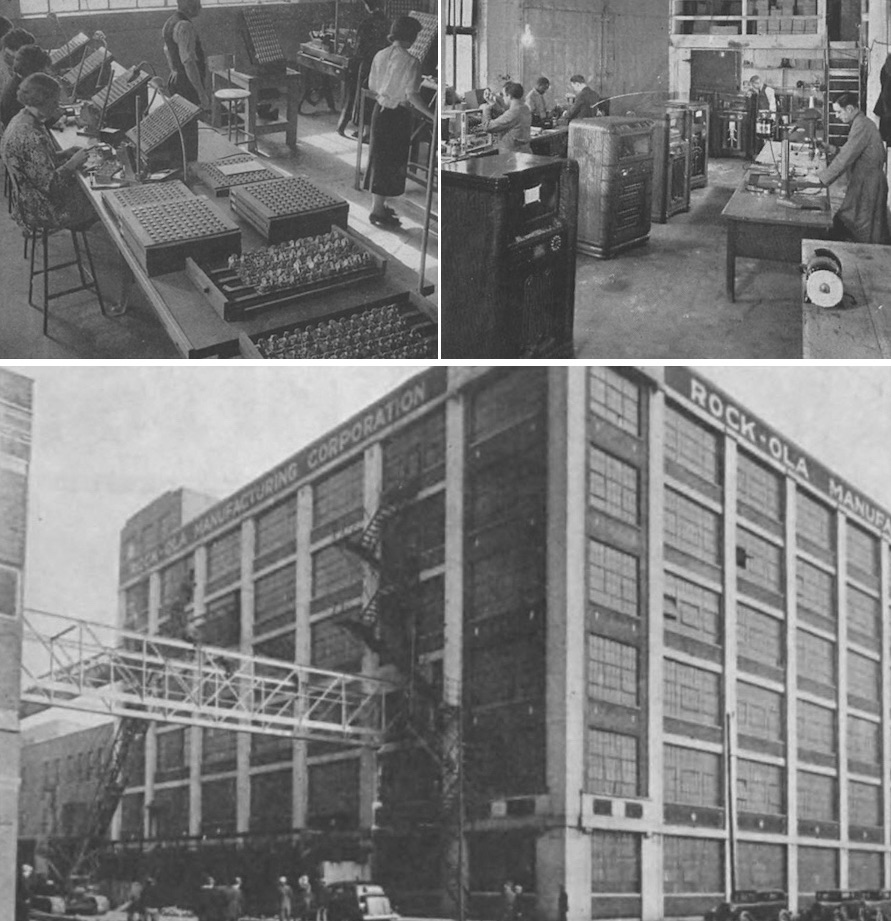

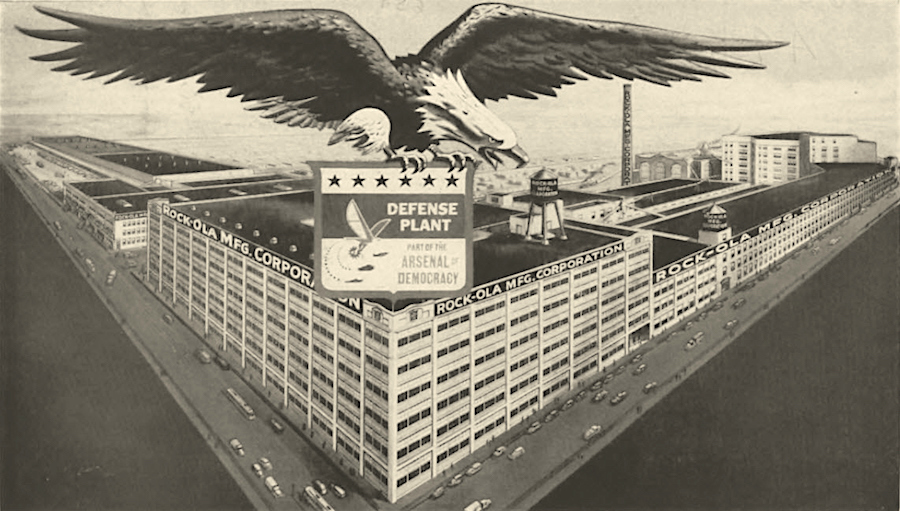

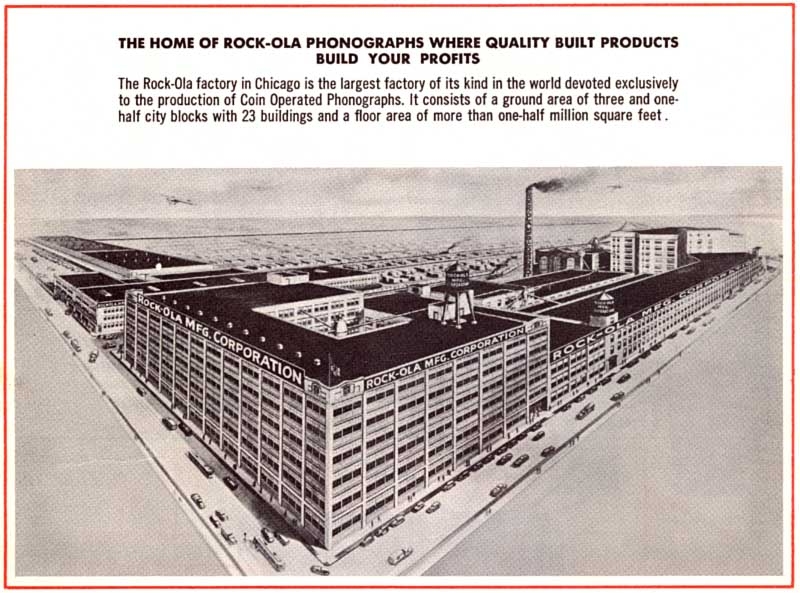

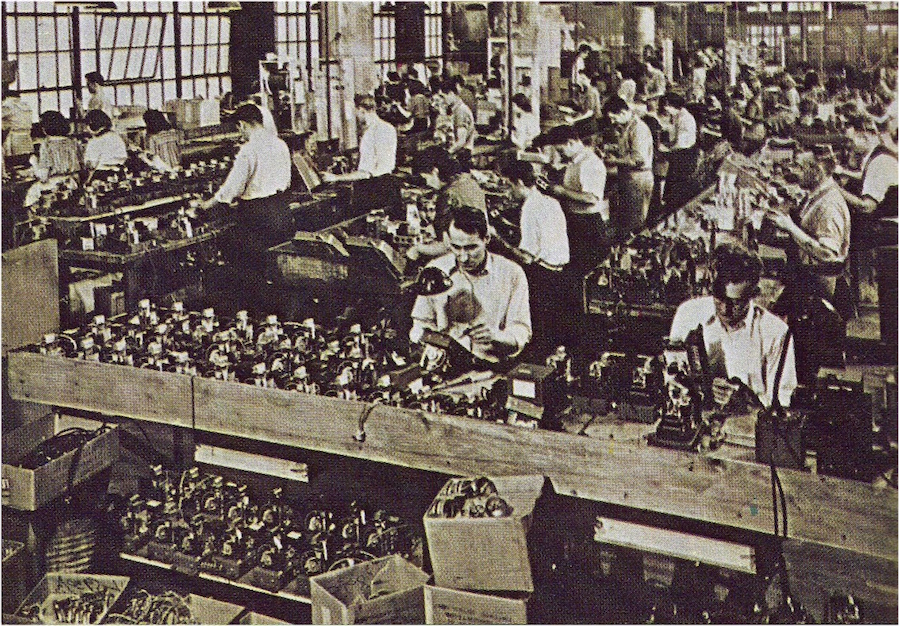

In 1934, when many factories were shrinking or shuttering, the Rockola MFG Corp. moved from a perfectly reasonable space at 625 West Jackson Blvd. to a massive 250,000 square foot monstrosity at the northwest corner of Chicago Avenue and Kedzie. The building’s previous owner, the Gulbransen Piano Company, stayed in business by leasing about one-third of the space from Rockola. The full deal, though, also included nineteen other small industrial buildings, totaling 600,000 square feet. Rumors swirled for years as to what might be going on in some of those facilities, but no raids ever occurred, and the company’s workforce continued to grow—reaching more than 3,000 men and women at its height.

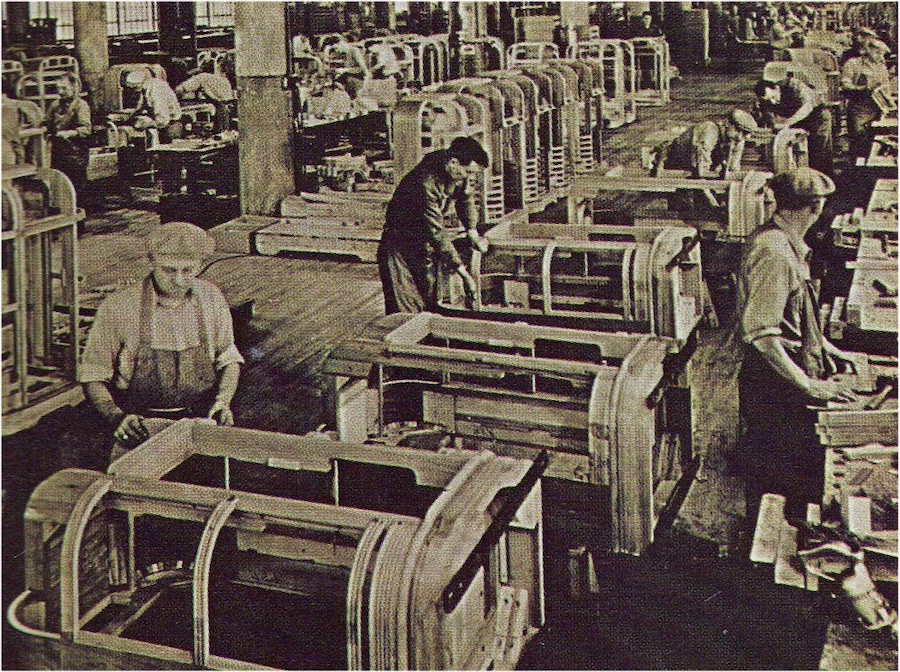

[Workers assembling machines at the new Rock-Ola factory at 800 North Kedzie Avenue, 1930s]

[Workers assembling machines at the new Rock-Ola factory at 800 North Kedzie Avenue, 1930s]

Thinking Inside the Box

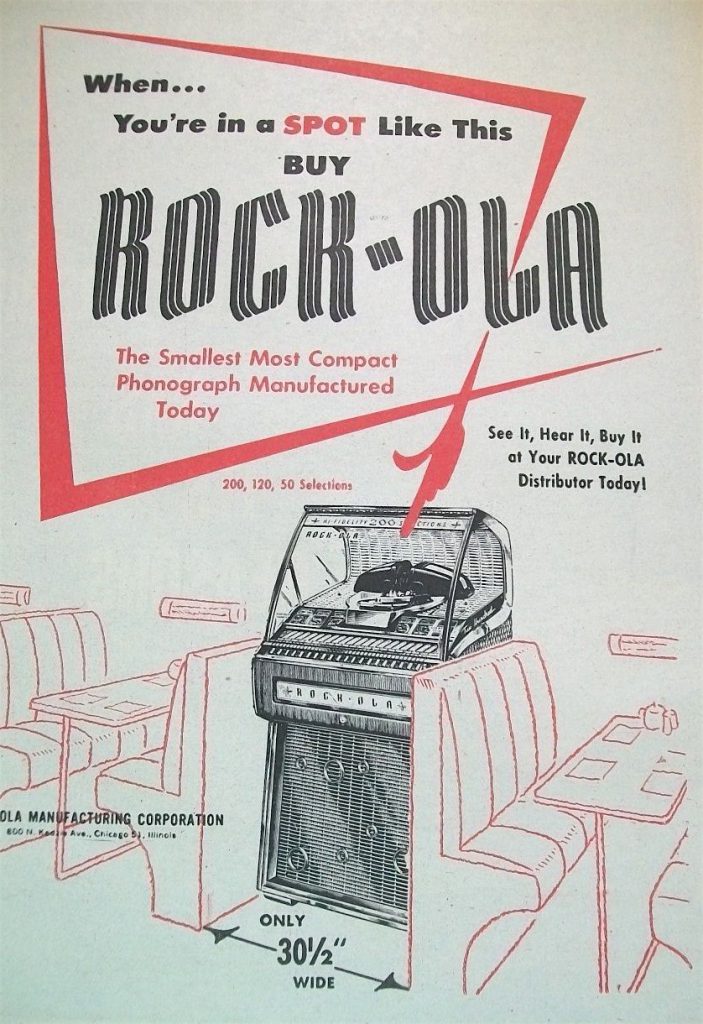

Within the first year at the Kedzie factory, Rockola—now officially known corporately as “Rock-Ola” (supposedly because David wanted people to pronounce his last name correctly)—started making “coin-operated phonographs.” The term “jukebox” didn’t actually enter the mainstream until a few years later.

In the mid 1930s, Wurlitzer was already well established in the field, and Seeburg was entrenched, as well. Seeing Rockola’s success in games and other coin-op products, the other jukebox giants supposedly offered him a deal to stay out of their arena. He naturally refused, launching what would be a long and contentious, if not entirely unfriendly, rivalry.

[Early models for jukebox cabinets at Rock-Ola basically just carried over the established shape of radio cabinets from the 1920s and ’30s.]

[Early models for jukebox cabinets at Rock-Ola basically just carried over the established shape of radio cabinets from the 1920s and ’30s.]

Purchasing some existing patents and adding some aesthetic tweaks, Rock-Ola debuted its first jukebox, the Multi-Selector, in 1935. It had just 12 song selections and stood four feet tall, but unlike some of its contemporaries, it allowed the user to pick multiple records at once, which the machine would “remember” in the chosen sequence. It set the tone for the company’s willingness to push the creative envelope, even if Seeburg and Wurlitzer might have had the technical superiority.

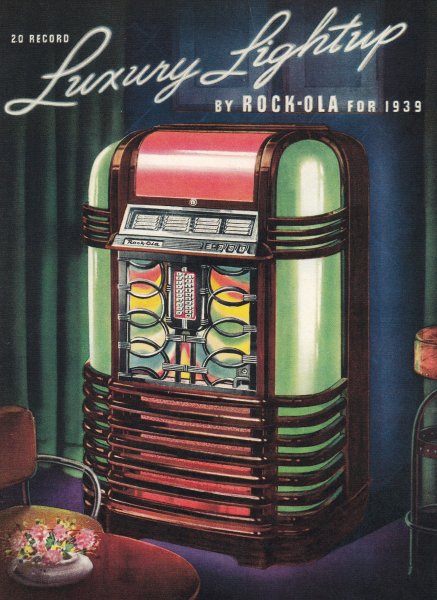

Come 1939, Rock-Ola had ticked its song count up to 20 per box (where they stayed through the entire 1940s) and introduced its first “Luxury Light Up” model—a colorful art deco cabinet that would become one of the standard bearers for our modern conception of the “classic jukebox.”

Come 1939, Rock-Ola had ticked its song count up to 20 per box (where they stayed through the entire 1940s) and introduced its first “Luxury Light Up” model—a colorful art deco cabinet that would become one of the standard bearers for our modern conception of the “classic jukebox.”

“Back then,” an older Rockola once said, “if someone had a new song, the first thing they wanted to do was get it on a jukebox, because that’s how everyone would hear it. It was the way people got to hear music—it was very important to them.”

The actual artistic nature of that music was notably of far less significance to Rockola. Whether it was Doris Day or The Doors, his business was the platform, not the message.

During World War II, the North Kedzie plant switched over much of its man power to building carbine rifles for the Allies, turning an underground bunker below the factory parking lot into a makeshift shooting range. The firearms have since become quite rare and collectible.

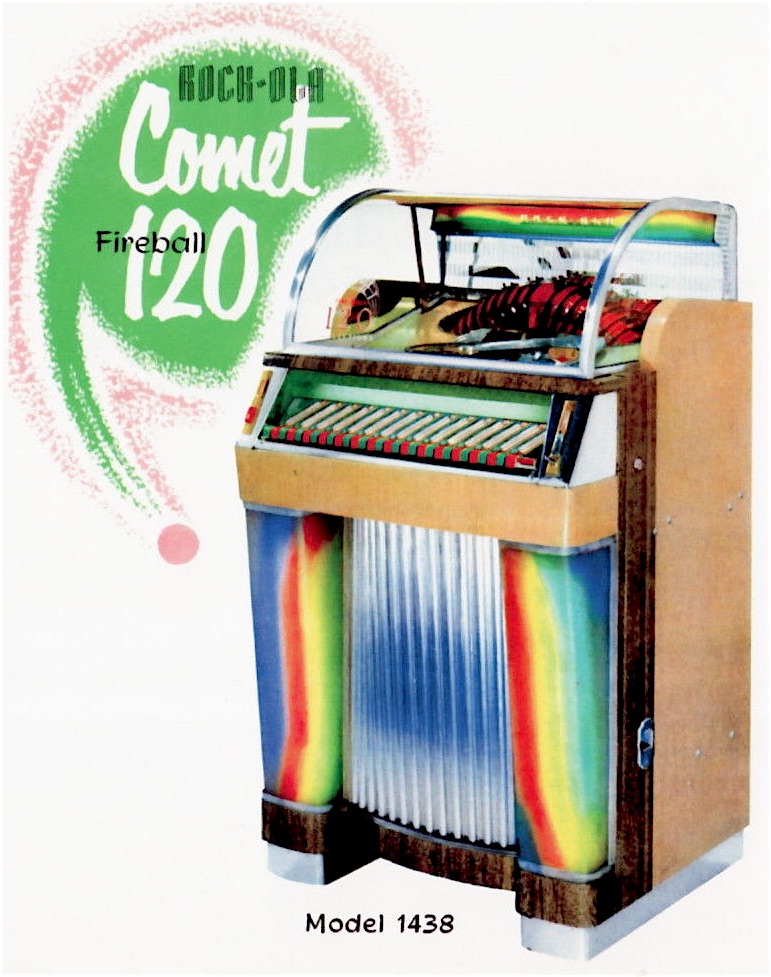

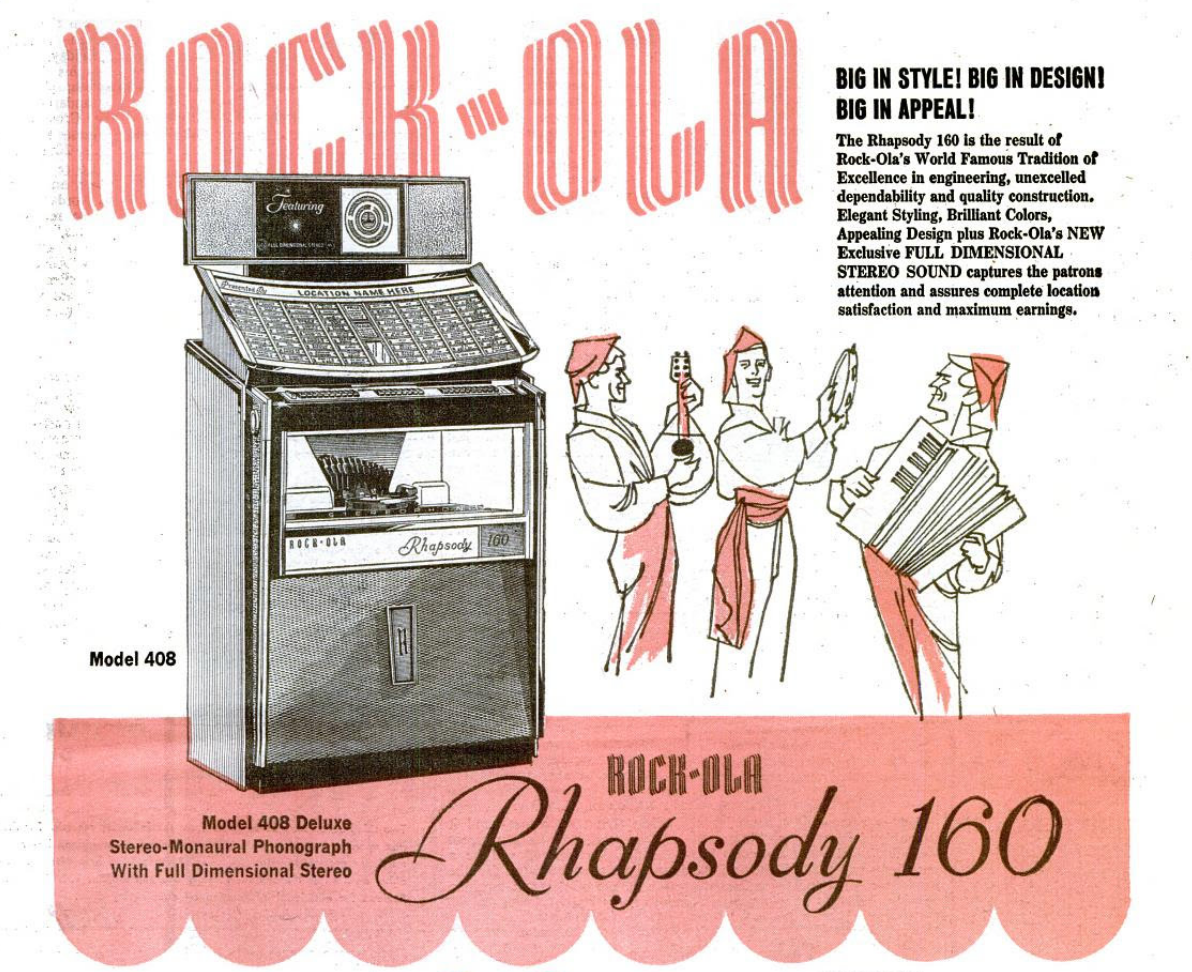

Even during wartime, though, Rockola and his lead designer David Kochole found time to roll out new jukes for the boys coming home. There was the “Spectravox” series, along with the “President,” “Commando,” and “Magic Glo.” And as the fancy oversized automobiles of the era began influencing the trends in the industry, the “Rocket,” “Comet Fireball” and “Tempo” models arrived as some of the defining machines of the post-war boom—by now offering between 120 and 200 song selections.

[The model 1438 Comet Fireball Jukebox was one of the full-size units compatible with our model 1546 Wall Box]

[The model 1438 Comet Fireball Jukebox was one of the full-size units compatible with our model 1546 Wall Box]

Behind the Music

By the 1960s, with David Rockola getting near retirement age, his son Donald started taking on a larger role in the company. Even so, David never strayed far from his creation. One of his longtime salesmen and assistants, Frank Schultz, saw his boss’s unwavering dedication on display every day.

By the 1960s, with David Rockola getting near retirement age, his son Donald started taking on a larger role in the company. Even so, David never strayed far from his creation. One of his longtime salesmen and assistants, Frank Schultz, saw his boss’s unwavering dedication on display every day.

“He worked seven days a week, sixteen hours a day,” an elderly Schultz recalled to author William Bunch in 1992, presumably exaggerating just a tad. “He ran this place with an iron fist. We’d have a staff meeting, and he’d come in and say, ‘Press number 16 wasn’t running, press number 18 wasn’t running, press number 22 wasn’t running—Why?!’ When he came in he walked through different floors every day. His eyes were always looking. I remember stories where he’d walk through the assembly line and see some part lying on the floor, and he’d say, ‘Would you throw money away like this at home?’”

No surprise—another Type A personality running a company in the Made In Chicago Museum. In the end, though—despite a hard-working life and an occasional enjoyment of cigarettes and booze—David C. Rockola lived well into his 90s. His company was a survivor, too, outlasting its old rivals Wurlitzer and Seeburg to escape the 1980s severely damaged, but still operational.

With Humboldt Park getting rougher and profits getting lower, the company was forced to abandon its mighty North Kedzie factory in 1985, moving to a sterile business park in Addison, Illinois (the Kedzie plant has since been demolished). And while the creation of CD jukeboxes briefly offered some hope of a second life, it was all too clear that Rock-Ola was trying to keep pace in a coin-operated horse race that no amount of wagers could win.

Following David Rockola’s death in 1992 at the age of 96, his son Donald Rockola (who’d been running the firm for some time) elected to sell the family business after 65 years.

The new ownership carried over some of the original Rock-Ola team to its operation in California, technically maintaining the company’s claim as the longest operating American jukebox manufacturer. But compared to the wall-to-wall production of the prime Kedzie years, when 25,000 jukeboxes could be produced in one year, the current factory is a humble project mostly for a diehard audience. Still, David Rockola would probably be pleased to know that his legacy lives on.

“People love music,” Rockola said in his later years, “and as long as they can play music that’s reasonable, and select what they want to hear, jukeboxes in some form will be around.”

Did Rockola care that his machines helped usher in a musical and cultural revolution? Eh, not so much. He became a naturalized American citizen and certainly took pride in his company’s accomplishments, but his motivations were generally that of a good merchant, not a revolutionary—rebellious past aside. Rockola’s old assistant Frank Schultz probably put it best: “I think in his mind, he just loved to give people entertainment at a reasonable cost.”

Not profound, maybe, compared to some of our rock n’ roll heroes. But it’ll do.

Sources:

Jukebox America : Down Back Streets and Blue Highways in Search of the Country’s Greatest Jukebox, by William Bunch (1994)

“Bare Slot Graft Charges Against Reid, Captains” – Chicago Tribune, November 28, 1929

“State’s Balky Slot Witness Sent to Jail” – Chicago Tribune, November 30, 1929

“The Rock-Ola Company” – Jitterbuzz.com

“David C. Rockola [Obituary]” – Talking Machine Review 83 (1993)

“Obituary: David C. Rockola” – The Independent, Feb 2, 1993

“I’m Walking, Yes, Indeed, But Not Talking: The Great 1929 Slot Machine Scandal” by John Bollinger, AmericanMafia.com

“The Story of Rock-Ola Video Games” – The Golden Age Arcade Historian

Archived Reader Comments:

“I was a service engineer for rockola from 1987 through 1997. I worked in addison with david rockola and frank shultz and worked for mr glenn streeter (torrance) for 5 years — correction : david rockola passed away then donald sold the company after his death” —David Massa, 2019

“I like that ’50s Chicago avenue photograph (looking west) because that’s how I remember the Rock-Ola factory building. One popular employee story at the time was one of his many ersatz foot-patrols (getting less frequent by 1969 when I started) the elder Mr. Rockola encountered a factory worker not particularly busy (and also not recognizing who confronted him) and asked (rhetorically we presume) “why aren’t you busy at your job?”, to which a reply was given “For what they pay me around here I can’t afford to work”. True the company wasn’t known for but modest wages and salaries but I do miss the place and the kind of work I did there in my younger years” —GVF, 2017

I have a Vintage Rock Ola and a Mills I would like to sell Does anyone have any Ideas….no ebay and no auctions and….only pick up or third party Thank you! Lauren

Pat ( Pralhad ) Patil

Mr David Rock Ola and Donald Rock Ola , I worked for them as a Q C Mgr from 1973 to

1985 . I was fortunate to work with the company and earned the respect and descent Wages .

I wish , I can talk and see Mr Donald Rock Ola

And anyone like to contact me is fine

1 847 312 0247 Cell

Looking for information about the company based out of Chicago named Park-O-Graph , I’m thinking it may be related to the Rock-Ole Company

Nothing comes up on google

I could email pictures it is very unique

Just thought I would share with anyone interested, there is a personally signed

David C Rockola Portrait Photograph from 1978 on Ebay https://www.ebay.com/itm/166297564133

Is there a US $ I can call.looking for support for a rockola 474. Manual, schematic.

What memories!!! I found items in your article that I didnt know. I worked for David Rockola and listened to his stories for 14 years first as his Executive Assistant and then as Executive Vice President of Rockola. What a run for the best company together with the most caring boss.

Hi Bette! If you have any specific stories about Mr. Rockola that you’d like us to include in the article, please email us at contact@madeinchicagomuseum.com. Would love to hear more! –Made in Chicago Museum

R any of the older rock Ola juke boxes available for sale from 1973 ??

As a young sales engineer in 1962 with Peoples Gas I found Mr. Rockola to be “all business.” I remember Mr. Rockola seated at his large desk… 5 young men standing in dark suits and black ties behind him… He sternly warned me about never lying to him… “shaking” I heeded his warning… I got the contract…

Our church has a Rock-Ola soda machine, model CCA6 7 I think the last number is hard to read. The front is labeled COLD DRINKS and has 6 soda cans. It says 50 cents on the coin area.

It also makes no mention of the Video Games that Rock-Ola made for a few years in the early 1980s, “Jump Bug” is the only one that I can name off the top of my head.

This is a great article, but there is no mention of the Rock-Ola Tournament Edition Shuffleboard Table, which was made between 1948 and 1950. It is the most iconic and sought after Shuffleboard Table ever made. Here’s a link: https://www.shuffleboardfederation.com/shuftabroc.html

Looking for a picture of Miss Rockola Betty Busch. Year would be early 1940’s.

She is a relative. Our family picture of her was burnt up in a house fire.

i have a rock-ola jukebox with serial# 006954 and the model # 478

could you tell what year this was made

my question is i have a rock-ola jukebox serial # 006964

model # 478 i want to know if you could tell me what year it is and

about how much it might be worth

I worked for Rockola Mfg. 1965 to 1979. A manager of the cable and wire dept. Not sure but I believe I am one of the few that receive a retirement check each month for the time working there. God bless the Rockola family. Best employment there of my working life. Lots of great memories.

I feel the same — Rockola was the best place i ever worked , with the nicest people to work with, we were all like family